Reclaiming the Nomadic Spirit

Learning from the Ways of the Kyrgyz People

|

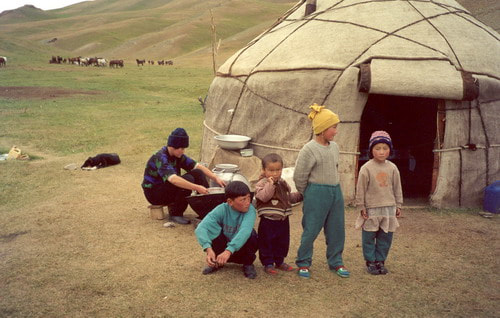

In the beginning, we humans were all nomads. We were hunters and gatherers. Then, after discovering agriculture and developing cities, some of us became sedentary. Indeed, most of us did. We lost something. I want to encourage us to reclaim our past for the sake of our future, with help from the Kyrgyz people and their nomadic traditions. There's no need to hunt and gather; but there is a tremendous need to learn from people who knew how to adjust, to move, to make do with what is available, and to establish rich social bonds along the way, believing in spiritual connections between people, animals, and the earth, and recognizing that, at some level, the building blocks of the universe are not "things" but rather "stories," some of them epic, like the Epic of Manas. These are a few of the lessons we an learn from the Kyrgyz people and their rich past.

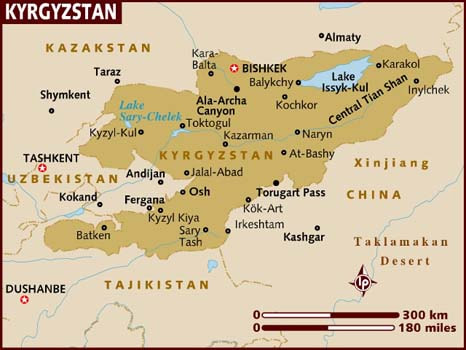

I am a college professor in the southern part of America, and I want my students to learn about the worldviews and ways of the people of Central Asia, in this case the Kyrgyz and their nomadic past. Additionally, I teach summer courses in China on "process and relational philosophy," a way of looking at life and the world that sees the whole of life organically, not mechanistically; and that stresses that we find value in life, not by seeing the world in terms of objects, but rather by seeing the world in terms of events. For us process thinkers, the whole universe is composed of "stories" not "things." I think the Kyrgyz People have something to offer here. As I learn about and from them, from gifted scholars such as Elmira Köchümkulova, I begin to think that their ways, including their nomadic past, is a possibility for the future, for all of us in a certain way. I'm voting for, as it were, a Kyrgyzing of our mindsets. Not outwardly but inwardly. Outwardly the nomadic side of life moves from place to place. This is no longer possible for most of us. Inwardly, the nomadic way is free to expand and explore - sensitive to the ways that the universe itself is expansive exploratory, not contained in merely "scientific" ways of knowing defined by the fallacy of simple location. It knows that things are located in many places simultaneously. People are not simply individuals: they are persons in community, originating out of their felt relationships and thus "present in" one another. An ancestor from the past can be there in the past but also here in our imaginations and in our songs. The same goes for people and the more-than-human world: hills, rivers, mountains, horses. The nomadic side of life is also capable of living faithfully and responsively to friends and family, grateful for ritual customs that hold life together, without insisting that all follow them. Marriage customs, for example. And the Kyrgys culture carries within it the courage, the ferocity, of the epic hero Manas, channeled toward a defense of what is good and beautiful. This page is offered in gratitude to scholars who teach us about Kyrgys culture, and to my students who want to learn from the Kyrgyz people and their customs. It is for educational purposes alone. -- Jay McDaniel, editor of Open Horizons |

I. A Word about "Nomadic" Religion Today

2. A Traditional Nomadic Wedding in Kyrgyzstan 3. The Bubu Shaman Women of Kyrgyzstan 4. The Epic of Manas 5. Some Final Reflectioins Kyrgyzstan |

Nomadic Religion

in central and northern Asia Today

Today it is a Syncreticism of Dispersed Shamanism

and Sufi-Influenced Islam or Buddhism

Excerpts

Syncretism between "Dispersed Shamanism" and Islam (among Turkish peoples) and Buddhism (among Mongols)

"Our subject here is traditional religion in Central Asia; we begin with what has been termed "dispersed shamanism." This set of pre-Islamic traditional religious beliefs and practices has lasted into modern times, at the same time that many of its practitioners have adopted one or another of the "religions of the book": in the case of the Mongols--Buddhism; and in the case of many of the related Turkic peoples of Central Asia-- Islam. As will become evident, there is a syncretism between pre-Islamic religious tradition and Islamic norms, a fact which explains some of the distinctive features of Central Asian Islamic practice."

-- Elmira Köçümkulkïzï and Daniel Waugh in Silk Road Seattle is a project of the Walter Chapin Simpson Center for the Humanities at the University of Washington: https://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/culture/religion/religion.html.

Rituals of Nomadic Peoples |

The Relationship between Nature and People The Syncretism of Islam and Dispersed Shamanism |

A "Fairytail" Kyrzyg Wedding

shared by Dr. Elmira Köçümkulkïzï

Video Clips from the Article"In this clip, according to a Kyrgyz tradition, my sisters-in-law and sisters are braiding my hair and helping me to put on my wedding dress and decorations. Traditionally, the bride’s hair is braided into kïrk chach, forty braids. Since I did not have long and thick hair, I told my sisters-in-law to make only four braids. On the tips of my braids I wore my paternal grandmother’s old silver hair decorations which she herself had worn when she married. My wedding costume is not a 100% traditional or authentic Kyrgyz bridal dress. It is a more modernized and stylized version of it. The shape of my shökülö, headdress, is traditional. In the past, some brides wore shökülö, some simply wore a big white scarf thrown over her head covering her face. In order to meet expectations people had for a “bridal” look, I wore everything in white. Were I to have the wedding again, I would wear a more colorful dress, vest and a shökülö." "Among all the ceremonies and rituals, the singing of the koshok, a farewell song to the bride, was the highlight of the wedding. The night before the actual wedding day, my two great aunts, my mother, i.e., paternal grandmother (I call her “Mom” because she raised me from the age of one until the age of six), and another distant aunt who sang the main wedding song to me, were preparing their eleçeks, traditional headdresses to wear on the next day during the singing ceremony of the wedding song. It was interesting to watch them making eleçeks by wrapping the long pieces of white cloth around each other’s head. They did not remember exactly how it was done correctly. So, they were making fun of each other. All four women wanted to participate at the singing ceremony. At the same time, however, they were a little bit shy to wear the headdress and sing in front of many people. They were also trying to recall the words of the wedding songs which they heard in the past. Since the singing of the wedding song was held in a traditional setting, i.e., inside the yurt where the bride was sitting with her girl friends and jenges, it was quite appropriate for the elderly women to put on the eleçeks to match the context of the scene. I could tell from people’s eyes that they were all, including the men, excited to see these traditional themes of the wedding." |

Excerpts from the Article"I wanted to share with you my wedding and the Kyrgyz nomadic life and culture in which I grew up, because the more we educate ourselves about other peoples and their culture, the more we develop respect towards each other’s way of life and worldview. Many often “the others” and their cultures get misinterpreted by westerners and western media, and it is important to listen to and learn from the “others” themselves about what they think about their customs and traditions." "Why was it important for me to have a traditional wedding with horses, camels, traditional clothes, koumiss (fermented mare’s milk), and yurts? It was my nomadic childhood experience in the mountains with my grandparents that led me to have the “fairy-tale” wedding. It was indeed a fairy-tale Kyrgyz wedding in modern times, but it would have been an ordinary wedding about sixty or seventy years ago." Photos from the Wedding

|

Bubu Shaman Women of Kyrgystan

Both Muslim and Shamanic

"The Bubu contributions to the religious life of Muslim women throughout Central Asia have been significant and should be studied further. When examined closely, it appears that the Bubu have challenged the traditional religious authority of male–dominated Muslim institutions in Central Asian societies, and have thus significantly shaped the daily, non-institutional religious practices of women. Within such a context, Bubu have inspired many Muslim women to support a variety of informal religious practices that, while not openly challenging Muslim Orthodoxies, have engendered private religious practices that have directly impacted many aspects of family life, particularly those centering on women’s and children’s health issues." |

An Article by Fatima Sartbaeva

The Epic of Manas

Click on button below for an excellent and accessible

introduction to the Epic of Manas offered by

Dr. Elmira Köçümkulkïzï

Excerpts

Manas, Shamanism, and Islam "Many often "the others" and their cultures get misinterpreted by westerners and western media, and it is important to listen to and learn from the 'others' themselves about what they think about their customs and traditions." A Little of the Text A Contemporary Performance in FilmManas Destânı - Dünyanın En Uzun Destânı

- Nursultan Dosaliev - Kırgızistan |

The Hero Manas Rhythms and Drama in the Voice[To obtain a sense of the rhythms of the epic and the drama of the recitation, listen to a sound recording of Elmira Köçümkulkïzï reciting in Kyrgyz a summary version of the "First Heroic Deed of Manas," transcribed from a performance by Sagymbay Orozbakov.]

Sufism and The Power of Music UNESCO Introduction to Epic of ManasI. In Manas

II. In Semetei

III. In Seitek

An Oceanic Epic without End |

Final Reflections

'Nomadic peoples share their lives in their stories: their oral epics, as in the Epic of Manas of the Kyrgyz of Kyrgyzstan. The stories are in the words, to be sure, but also in the performances, the rhythms, the sounds. the creativity, as offered and received among a unique people. The brilliance of the Epic of Manas reminds us that most people -- central Asian but also western -- find meaning in life, not simply through words on a page or a screen, but in the living word, sung and danced. The very force of Manas as chanted becomes, for us westerners, not a relic from the past but an ocean of possibility from the future. We are reminded that we, too, need to sing our way into the future in stories, in song, and make space for others to do the same, on their terms and in their ways.

No, our songs cannot be of the ferocious type. We cannot and need not foist calamity on others, covering them with blood and dust. That is for an earlier age, when struggle for survival may have required violence of this sort. Who is to judge? But may the spirit of that ferocity now be directed toward compassionate ways of being in the world, one form of which is a listening to, and an enjoyment of, the heroic tale. Let our song be a listening.

Few Westerners have heard of the Epic of Manas, but almost all Kyrgyz know of it. (There are even heavy metal bands that have written their own versions of the Epic. See Darkestra: Manas.) After reading Elmira Köçümkulkïzï, three topics come to mind that are important to Open Horizons (Process) thinkers, or, as we speak of ourselves in China, "constructive postmodernists."

Oral Creativity versus Written Creativity: With its orality, The Epic of Manas reminds us that this privileging of the written text over the sung story is a prejudice of print-based culture. Oral Creativity and Written Creativity have their gifts, and neither needs to valorized over the other.

Ethnic Nationalism and Civic Nationalism: In Kyrgystan the Epic of Manas functions as a catalyst for ethnic nationalism: that is, nationalism in which peoplehood is defined by a shared heritage, shared language, shared values, and shared ethnicity. The opposite of such nationalism is multicultural, democratic nationalism, in which peoplehood is defined in terms of common citizenry but not common ethnicity. One challenge of the twenty-first century, faced by many multicultural nationalists, is to understand the need and desire for ethnic nationalism, felt by many - and to seek ways of reconciling this with multicultural, democratic nationalism. The current state of affairs in the world, as represented by internationalists who emphasis globalization, often helps very little, because it leaves power in the hands of global elites.

Shamanic Religion and Abrahamic Religion: In its current versions the Epic of Manas combines two traditions: (1) early Nomadic culture with its Shamanic values and (2) a more recent Islamic culture now adopted by the vast majority of Kyrgyz. One value of Dr. Köçümkulkïzïs that she does not draw a dichotomy between these two strands of the epic, but instead sees them as mutually infusing and complementary, not contradictory.

In short, there are at least eight reasons to learn about, and from, the Epic of Manas.

No, our songs cannot be of the ferocious type. We cannot and need not foist calamity on others, covering them with blood and dust. That is for an earlier age, when struggle for survival may have required violence of this sort. Who is to judge? But may the spirit of that ferocity now be directed toward compassionate ways of being in the world, one form of which is a listening to, and an enjoyment of, the heroic tale. Let our song be a listening.

Few Westerners have heard of the Epic of Manas, but almost all Kyrgyz know of it. (There are even heavy metal bands that have written their own versions of the Epic. See Darkestra: Manas.) After reading Elmira Köçümkulkïzï, three topics come to mind that are important to Open Horizons (Process) thinkers, or, as we speak of ourselves in China, "constructive postmodernists."

Oral Creativity versus Written Creativity: With its orality, The Epic of Manas reminds us that this privileging of the written text over the sung story is a prejudice of print-based culture. Oral Creativity and Written Creativity have their gifts, and neither needs to valorized over the other.

Ethnic Nationalism and Civic Nationalism: In Kyrgystan the Epic of Manas functions as a catalyst for ethnic nationalism: that is, nationalism in which peoplehood is defined by a shared heritage, shared language, shared values, and shared ethnicity. The opposite of such nationalism is multicultural, democratic nationalism, in which peoplehood is defined in terms of common citizenry but not common ethnicity. One challenge of the twenty-first century, faced by many multicultural nationalists, is to understand the need and desire for ethnic nationalism, felt by many - and to seek ways of reconciling this with multicultural, democratic nationalism. The current state of affairs in the world, as represented by internationalists who emphasis globalization, often helps very little, because it leaves power in the hands of global elites.

Shamanic Religion and Abrahamic Religion: In its current versions the Epic of Manas combines two traditions: (1) early Nomadic culture with its Shamanic values and (2) a more recent Islamic culture now adopted by the vast majority of Kyrgyz. One value of Dr. Köçümkulkïzïs that she does not draw a dichotomy between these two strands of the epic, but instead sees them as mutually infusing and complementary, not contradictory.

In short, there are at least eight reasons to learn about, and from, the Epic of Manas.

- It offers a way of introducing the world to the traditional nomadic of the Kyrzyg people: their history, their philosophy, their spirituality. In the language of Dr. Köçümkulkïzïs, it helps the rest of the world better interpret, and understand, a unique people, without "othering" them.

- It empowers the Kyrzygs to enjoy a sense of ethnic nationalism. As a saying goes: "Every Kyrzg appreciates two books: The Qur'an and the Epic of Manas."

- It reveals the evolutionary nature of epics, how they evolve through time and change in their medium of expression. It is now being rendered into various kinds of performing arts, including film.

- It reveals the power of oral epics and, thus, the power of hearing, helping us overcome a western-influenced prejudice for written texts.

- It reminds us that hearing is a bodily activity, not just an activity of the ears, revealing the power of "musicking" - that is the act of music that is created in a participatory way, by listeners as well as performers.

- It presents us with the images of heroes who, while ferocious, and also inspire with their courage, reminding us to take the "energy" of the hero and apply it in our way, preferably non-violent.

- It provides energy for life in its own right, by virtue of its sonic power. When heard, even if you don't understand the words, revealing a world of sonic pulses that transmit energy and vitality in their own right.

- Its worldview challenges the hegemony of a European ways of thinking -- which are scientistic in that they've made a god of science -- inviting into a more organic, constructively postmodern way of thinking about the world which affirms the interfluidity and interconnected nature of all things, human and more-than-human.

Most of us will never know the fulness of nomadic living. Still we may partake of the spirit of nomadism in at least one way. By means of the internet and other forms of mass communication, they -- we -- find ourselves travelling from place to place, momentarily "settling" in one location for a time and then resettling in another. Our minds are nomadic even if our bodies are sedentary.

The digital age is producing a new kind of nomadic mentality. We might call it postmodern nomadism. Of course we may not bring with us some of the sorely needed values of nomadic peoples: a sense that the whole of the world is alive in some way, a respect for the spirits within nature, an appreciation of the aural and oral side of life, an appreciation of community. We may be deconstructively postmodern rather than constructively constructively postmodern.

For my part, I side with the constructive postmodernists. That's the phrase used in China today for a way of thinking that seeks to move beyond the pretenses and homogenizations of western modernity, with its valorization of "science" and its dismissal of traditional cultures, with its insistence on a single way of being in the world: "modern" and "industrial."

That one reason among many that we need to learn from traditional nomadic peoples, even as they, too, are evolving in postmodern ways. That is why we need to learn, for example, from the Kyrgyz and their Epic of Manas, and from the Bubu Shaman women. From all of it. That learning is what we mean by "constructive" postmodernism.

The digital age is producing a new kind of nomadic mentality. We might call it postmodern nomadism. Of course we may not bring with us some of the sorely needed values of nomadic peoples: a sense that the whole of the world is alive in some way, a respect for the spirits within nature, an appreciation of the aural and oral side of life, an appreciation of community. We may be deconstructively postmodern rather than constructively constructively postmodern.

For my part, I side with the constructive postmodernists. That's the phrase used in China today for a way of thinking that seeks to move beyond the pretenses and homogenizations of western modernity, with its valorization of "science" and its dismissal of traditional cultures, with its insistence on a single way of being in the world: "modern" and "industrial."

That one reason among many that we need to learn from traditional nomadic peoples, even as they, too, are evolving in postmodern ways. That is why we need to learn, for example, from the Kyrgyz and their Epic of Manas, and from the Bubu Shaman women. From all of it. That learning is what we mean by "constructive" postmodernism.