- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

Mermaids: Tales from the Deep

"We delve into the watery depths of sea creature folklore, with a round-the-world tour of different variations on the concept of mermaids – from the Sirens of Greek mythology to the Selkies or Seal Folk of Scottish legend, and water spirits known as Mami Water, which are venerated in parts of Africa and the Americas. Not forgetting the famous fairy tale, The Little Mermaid, which has captivated the imagination ever since its publication in 1837 and was popularised by Disney in the 1980s.

Joining Bridget Kendall to discuss what these ancient stories can tell us are Cristina Bacchilega of the University of Hawaii, co-editor of The Penguin Book of Mermaids; British writer, Marcelle Mateki Akita, who has written a book for children called Fatama and Mami Wata's Secret; and Lynn Barbour, founder and Arts Director of the Orkney Folklore and Storytelling Centre in the Orkney Islands in Scotland."

Produced by Jo Impey for the BBC World Service.

Joining Bridget Kendall to discuss what these ancient stories can tell us are Cristina Bacchilega of the University of Hawaii, co-editor of The Penguin Book of Mermaids; British writer, Marcelle Mateki Akita, who has written a book for children called Fatama and Mami Wata's Secret; and Lynn Barbour, founder and Arts Director of the Orkney Folklore and Storytelling Centre in the Orkney Islands in Scotland."

Produced by Jo Impey for the BBC World Service.

Swimming in the Depths

Whitehead, Mermaids, and Water Spirits

We are all mermaids. Or merfolk, if you wish. We all emerged from the watery depths of amniotic fluid in a mother's womb and, more distantly, from single-celled organisms that formed in the oceans billions of years ago. Our closer ancestors, mammals, also emerged this way. Mammals are thought to originally have been reptile-like creatures that lived in the water or near the water some 340 million years ago. As a result, we carry memories of living in water, and those memories affect how we live in the world. We have a sense of watery depths: a personal unconscious, a collective unconscious, a universal unconscious. In dreams and altered states of consciousness, and when immersed in music and the natural world, we swim in these depths, even if stuck on very dry land.

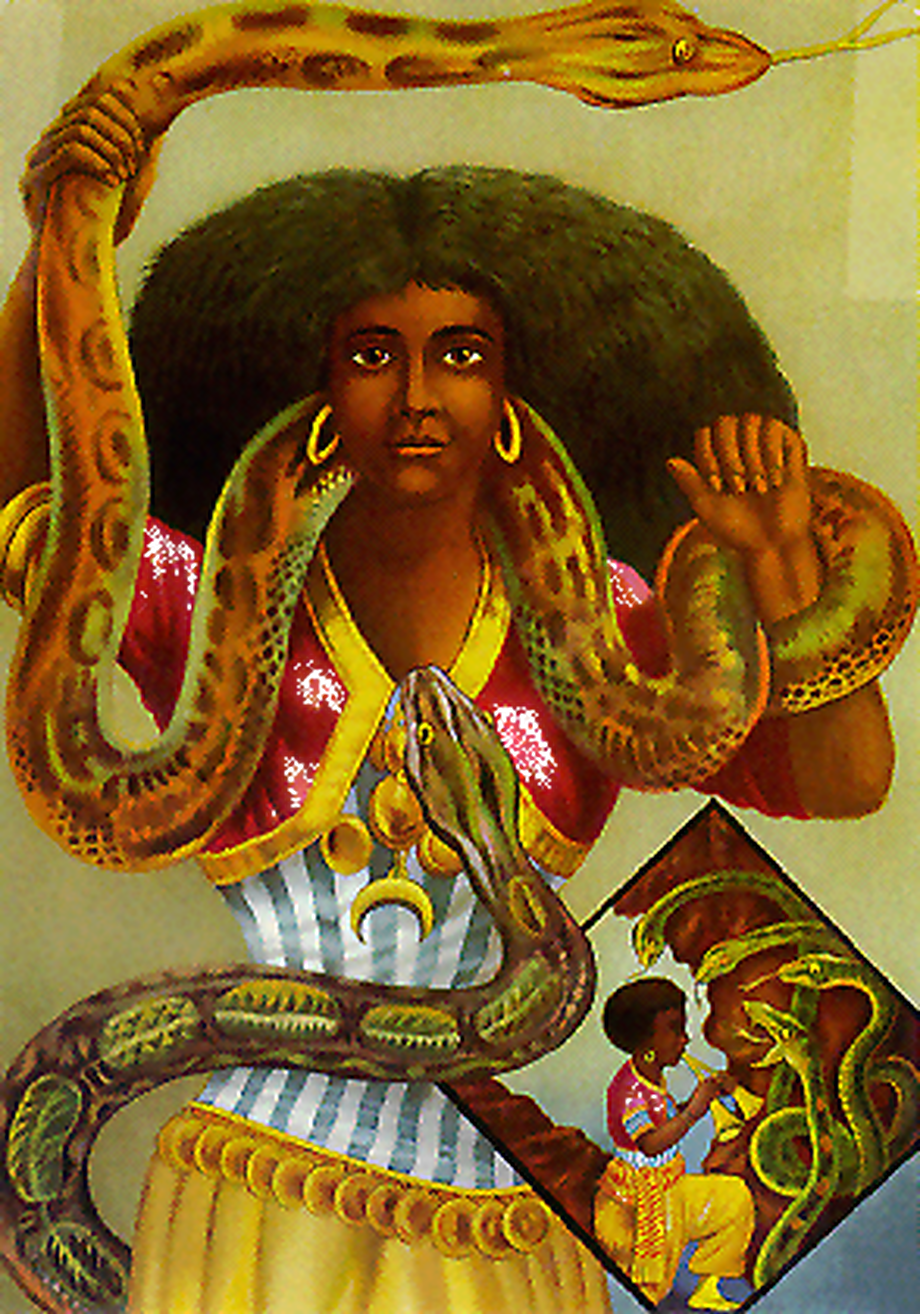

We also have images of water deities who protect the water kingdom: Mami Wata, for example, in West Africa and the Americas as described in the BBC podcast above. She is a symbol of sorrow and hope, connecting people of African descent back to Africa. Beautiful and powerful, she re-presents in localized form. She is God en-watered.

Whitehead offers a way of thinking about the human psyche, the universe as a whole, and God as Fluid in these various ways. A sense of fluidity is by no means the whole of Whitehead's vision. He is also interested in permanence and speaks of a non-temporal side of God. But Whitehead understands the actual world itself and the consequent nature of God as fluid and flowing: a creative advance into novelty together. It is as if we are always swimming in a vast ocean both worldly and divine. The Depths are within us, to be sure, and also outside us. We are all mermaids, enfolded within the fluidity of the Water Spirit.

Sometimes this swimming can be wonderful, sometimes terrible, and oftentimes somewhere in between. We always swim with others: other people, to be sure, and also the more-than-human world. Our swimming can involve diving into the wreckage of past experiences, individual and collective, happy and sad. Adrienne Rich puts it well in her poem below:

This is the place.

And I am here, the mermaid whose dark hair

streams black, the merman in his armored body.

We circle silently

about the wreck

we dive into the hold.

I am she: I am he.

- Jay McDaniel

We also have images of water deities who protect the water kingdom: Mami Wata, for example, in West Africa and the Americas as described in the BBC podcast above. She is a symbol of sorrow and hope, connecting people of African descent back to Africa. Beautiful and powerful, she re-presents in localized form. She is God en-watered.

Whitehead offers a way of thinking about the human psyche, the universe as a whole, and God as Fluid in these various ways. A sense of fluidity is by no means the whole of Whitehead's vision. He is also interested in permanence and speaks of a non-temporal side of God. But Whitehead understands the actual world itself and the consequent nature of God as fluid and flowing: a creative advance into novelty together. It is as if we are always swimming in a vast ocean both worldly and divine. The Depths are within us, to be sure, and also outside us. We are all mermaids, enfolded within the fluidity of the Water Spirit.

Sometimes this swimming can be wonderful, sometimes terrible, and oftentimes somewhere in between. We always swim with others: other people, to be sure, and also the more-than-human world. Our swimming can involve diving into the wreckage of past experiences, individual and collective, happy and sad. Adrienne Rich puts it well in her poem below:

This is the place.

And I am here, the mermaid whose dark hair

streams black, the merman in his armored body.

We circle silently

about the wreck

we dive into the hold.

I am she: I am he.

- Jay McDaniel

Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=275403

Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=275403

"To win the favor of Mami Wata, one must be clean and sweet-smelling both inside and out. Worshipers bathe and drink talcum powder before approaching her altar, neatly decorated with fruit, shells, porcelain artifacts, a mirror and combs. The smell of perfume hangs in the air.

The sound of crashing waves echoes through the exhibit when you first meet Mami Wata. Three of her characteristics immediately stick out. First is that she is half-human and half-fish, most often, resembling a mermaid. Second is that she possesses long, flowing hair. The third is that she can charm snakes. Now this may seem odd, considering she is a water deity, but certain snakes (like anacondas) are aquatic creatures and can be found in the waters in and around Africa.

Mami Wata is known for her beauty. But she is as seductive as she is dangerous. Those who pay tribute to her know her as a "capitalist" deity because she can bring good (or bad) fortune in the form of money. This relationship between currency and water makes sense. Her persona developed between the 15th and 20th centuries, as Africa became more present in global trade. The fact that the name Mami Wata is in pidgen English, the language used to facilitate this trade, shows the influence on foreign cultures on the spirit's image and identity."

- Joseph Caputo former editorial intern for Smithsonian and now a freelance science writer and editor based in Boston, Massachusetts.

Diving into the Wreck

Adrienne Rich

First having read the book of myths,

and loaded the camera,

and checked the edge of the knife-blade,

I put on

the body-armor of black rubber

the absurd flippers

the grave and awkward mask.

I am having to do this

not like Cousteau with his

assiduous team

aboard the sun-flooded schooner

but here alone.

There is a ladder.

The ladder is always there

hanging innocently

close to the side of the schooner.

We know what it is for,

we who have used it.

Otherwise

it is a piece of maritime floss

some sundry equipment.

I go down.

Rung after rung and still

the oxygen immerses me

the blue light

the clear atoms

of our human air.

I go down.

My flippers cripple me,

I crawl like an insect down the ladder

and there is no one

to tell me when the ocean

will begin.

First the air is blue and then

it is bluer and then green and then

black I am blacking out and yet

my mask is powerful

it pumps my blood with power

the sea is another story

the sea is not a question of power

I have to learn alone

to turn my body without force

in the deep element.

And now: it is easy to forget

what I came for

among so many who have always

lived here

swaying their crenellated fans

between the reefs

and besides

you breathe differently down here.

I came to explore the wreck.

The words are purposes.

The words are maps.

I came to see the damage that was done

and the treasures that prevail.

I stroke the beam of my lamp

slowly along the flank

of something more permanent

than fish or weed

the thing I came for:

the wreck and not the story of the wreck

the thing itself and not the myth

the drowned face always staring

toward the sun

the evidence of damage

worn by salt and sway into this threadbare beauty

the ribs of the disaster

curving their assertion

among the tentative haunters.

This is the place.

And I am here, the mermaid whose dark hair

streams black, the merman in his armored body.

We circle silently

about the wreck

we dive into the hold.

I am she: I am he

whose drowned face sleeps with open eyes

whose breasts still bear the stress

whose silver, copper, vermeil cargo lies

obscurely inside barrels

half-wedged and left to rot

we are the half-destroyed instruments

that once held to a course

the water-eaten log

the fouled compass

We are, I am, you are

by cowardice or courage

the one who find our way

back to this scene

carrying a knife, a camera

a book of myths

in which

our names do not appear.

Whitehead and Flow

"That ‘all things flow’ is the first vague generalization which the unsystematized, barely analysed, intuition of men has produced. It is the theme of some of the best Hebrew poetry in the Psalms; it appears as one of the first generalizations of Greek philosophy in the form of the saying of Heraclitus; amid the later barbarism of Anglo-Saxon thought it reappears in the story of the sparrow flitting through the banqueting hall of the Northumbrian king; and in all stages of civilization its recollection lends its pathos to poetry. Without doubt, if we are to go back to that ultimate, integral experience, unwarped by the sophistications of theory, that experience whose elucidation is the final aim of philosophy, the flux of things is one ultimate generalization around which we must weave our philosophical system."

Whitehead, Alfred North. Process and Reality (Gifford Lectures Delivered in the University of Edinburgh During the Session 1927-28) (p. 208). Free Press. Kindle Edition.

Whitehead, Alfred North. Process and Reality (Gifford Lectures Delivered in the University of Edinburgh During the Session 1927-28) (p. 208). Free Press. Kindle Edition.

Life from the Oceans

"The origin of life on Earth is still the subject of scientific investigation and debate, but the most widely accepted theory is that life originated in the oceans. This is based on the fact that the oceans provide many of the conditions that are necessary for life to emerge and thrive, such as a stable source of heat, water, and various chemicals that can serve as building blocks for life. Additionally, the oceans provide a large and relatively protected environment in which complex molecules can interact and evolve over long periods of time.

It's believed that the first living organisms were simple, single-celled organisms that formed spontaneously in the oceans billions of years ago. Over time, these organisms evolved and diversified into the wide variety of life forms we see today, including plants, animals, and humans.

While the exact details of how and when life originated in the oceans remain a mystery, scientists continue to study this fascinating question and make new discoveries that help us understand the origins of life on our planet."

- chatGPT

It's believed that the first living organisms were simple, single-celled organisms that formed spontaneously in the oceans billions of years ago. Over time, these organisms evolved and diversified into the wide variety of life forms we see today, including plants, animals, and humans.

While the exact details of how and when life originated in the oceans remain a mystery, scientists continue to study this fascinating question and make new discoveries that help us understand the origins of life on our planet."

- chatGPT

The Penguin Book of Mermaids

'Among the oldest and most popular mythical beings, mermaids and other merfolk have captured the imagination since long before Ariel sold her voice to a sea witch in the beloved Disney film adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen's "The Little Mermaid." As far back as the eighth century B.C., sailors in Homer's Odyssey stuffed wax in their ears to resist the Sirens, who lured men to their watery deaths with song. More than two thousand years later, the gullible New York public lined up to witness a mummified "mermaid" specimen that the enterprising showman P. T. Barnum swore was real.

The Penguin Book of Mermaids is a treasury of such tales about merfolk and water spirits from different cultures, ranging from Scottish selkies to Hindu water-serpents to Chilean sea fairies. A third of the selections are published here in English for the first time, and all are accompanied by commentary that explores their undercurrents, showing us how public perceptions of this popular mythical hybrid--at once a human and a fish--illuminate issues of gender, spirituality, ecology, and sexuality.'

The Penguin Book of Mermaids is a treasury of such tales about merfolk and water spirits from different cultures, ranging from Scottish selkies to Hindu water-serpents to Chilean sea fairies. A third of the selections are published here in English for the first time, and all are accompanied by commentary that explores their undercurrents, showing us how public perceptions of this popular mythical hybrid--at once a human and a fish--illuminate issues of gender, spirituality, ecology, and sexuality.'