Photo by Cullan Smith on Unsplash

Teilhard's Fire: Don Viney

"Someday, after space, the winds, the tides, gravitation, we will master, for God, the energies of love.

And then, for a second time in the history of the World, Man will have discovered Fire."

Teilhard de Chardin

Donald Wayne (Don) Viney is a philosopher and singer-songwriter influenced by Teilhard de Chardin, Charles Hartshorne, Alfred North Whitehead, and a less well-known but important philosopher named Jules Lequyer, sometimes called the French Kierkegaard. Lequyer’s ideas anticipated “open horizon” ways of thinking about humanity and God: emphasizing each as self-creative amid their interactions with one another. On this page you will learn about these thinkers, and also about Don’s own ideas. You have two sources: the songs he writes and sings, and excerpts from Don's writings. The purpose of this page is to introduce Open Horizon readers to Don Viney, his music, and his ideas - and to encourage others to follow in Don's footsteps, rendering important ideas and approaches to life into song and text. (Jay McDaniel)

About Don Viney *

Areas of Specialization

Process Philosophy

Philosophy of Religion

Logic and Critical Thinking

Charles Hartshorne

Jules Lequyer

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

"I was born and raised in central Oklahoma. When I entered my teens, the family moved to Fort Collins, Colorado where I attended Junior High and High School. I was admitted to Colorado State University as a music major (voice) but discovered that the theory classes were academically beyond me, so I turned to something easier: philosophy.

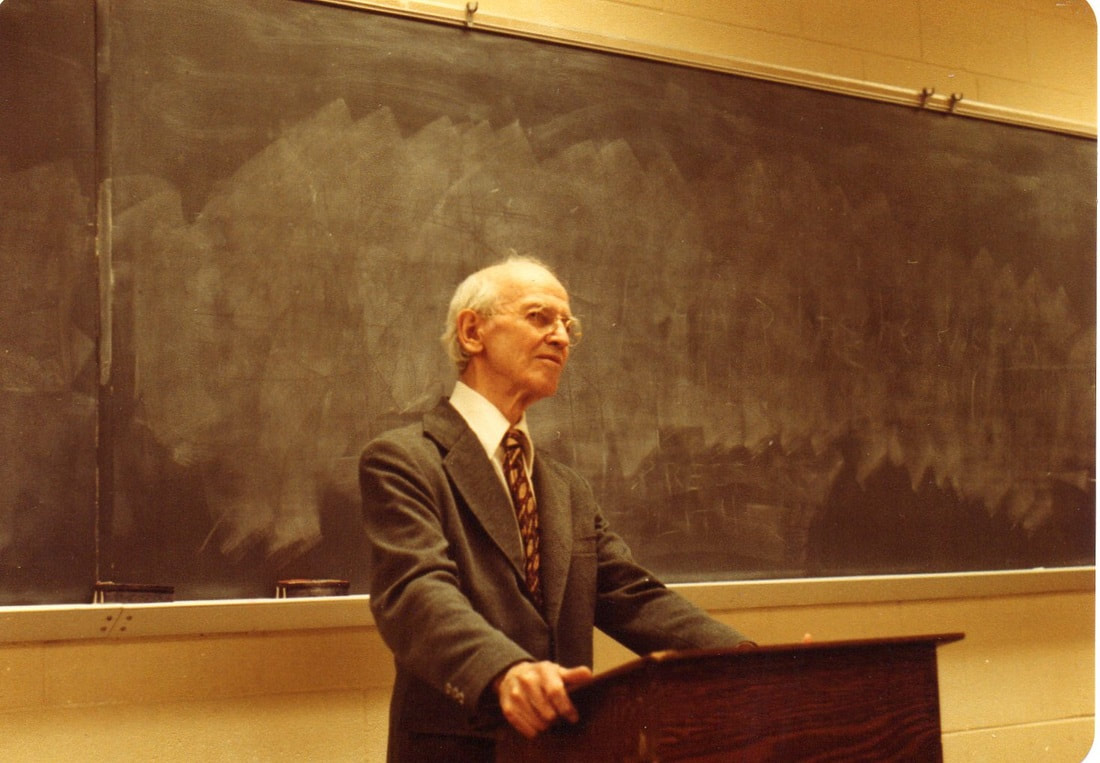

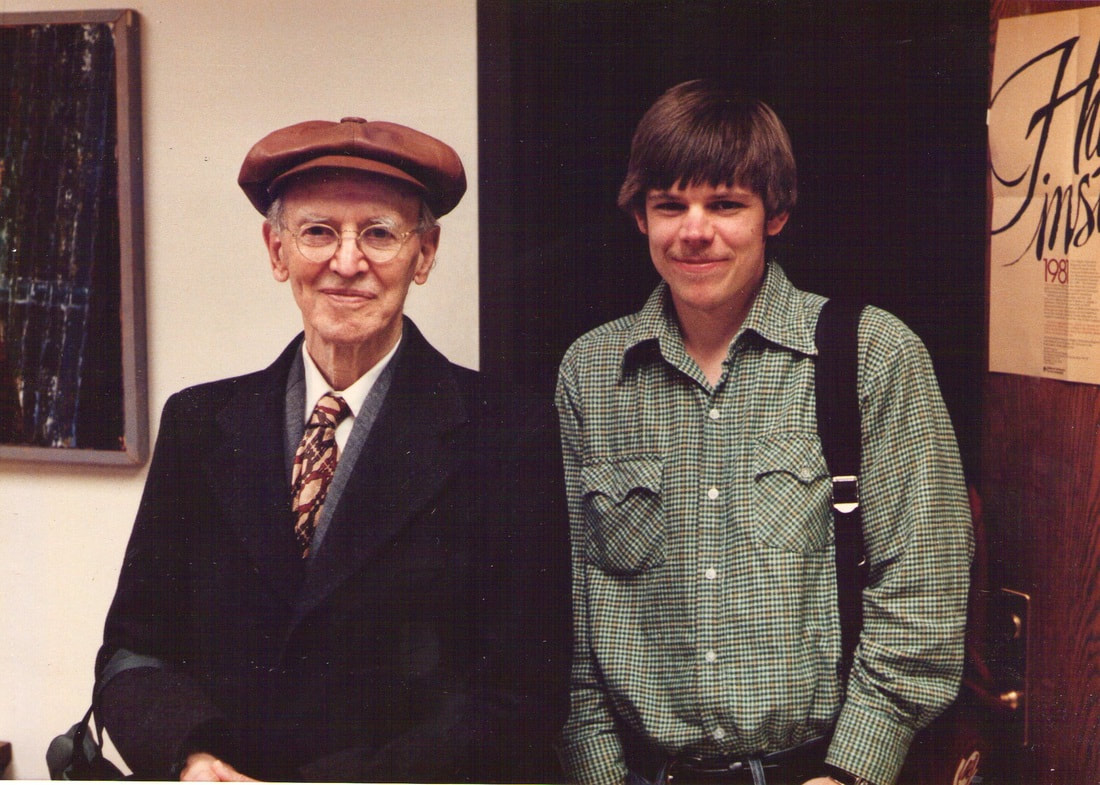

I studied with many fine philosophers and religious scholars at CSU, including Donald Crosby, Bernard Rollin, Grant Lee, and Winston King. I pursued graduate work in philosophy at the University of Oklahoma, and again I found many able philosophers, including J. N. Mohanty, Kenneth Merrill, and Francis Kovach. I wrote a dissertation on the philosophy of Charles Hartshorne, with Professor Hartshorne (who was at the University of Texas-Austin) as chief advisor. After completing the doctorate, I taught for two years at OU and at East Central University (Ada, Oklahoma). I have been teaching philosophy and religion at Pittsburg State University since 1984. Since high school I’ve dabbled in music, singing in choirs and folk bands. I compose songs for the guitar and, from time to time, I give a public performance.

Since 2008, I have made a few studio recordings of my music. Music theory continues to challenge me. Dr. Viney was honored with the 1989 Outstanding Faculty Award by the Student Government Association from the student nominees of faculty that demonstrate excellence in instruction and service to students on campus."

* from Pittsburg State University Faculty Page: http://www.pittstate.edu/faculty-staff/donald-w-viney

Process Philosophy

Philosophy of Religion

Logic and Critical Thinking

Charles Hartshorne

Jules Lequyer

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

"I was born and raised in central Oklahoma. When I entered my teens, the family moved to Fort Collins, Colorado where I attended Junior High and High School. I was admitted to Colorado State University as a music major (voice) but discovered that the theory classes were academically beyond me, so I turned to something easier: philosophy.

I studied with many fine philosophers and religious scholars at CSU, including Donald Crosby, Bernard Rollin, Grant Lee, and Winston King. I pursued graduate work in philosophy at the University of Oklahoma, and again I found many able philosophers, including J. N. Mohanty, Kenneth Merrill, and Francis Kovach. I wrote a dissertation on the philosophy of Charles Hartshorne, with Professor Hartshorne (who was at the University of Texas-Austin) as chief advisor. After completing the doctorate, I taught for two years at OU and at East Central University (Ada, Oklahoma). I have been teaching philosophy and religion at Pittsburg State University since 1984. Since high school I’ve dabbled in music, singing in choirs and folk bands. I compose songs for the guitar and, from time to time, I give a public performance.

Since 2008, I have made a few studio recordings of my music. Music theory continues to challenge me. Dr. Viney was honored with the 1989 Outstanding Faculty Award by the Student Government Association from the student nominees of faculty that demonstrate excellence in instruction and service to students on campus."

* from Pittsburg State University Faculty Page: http://www.pittstate.edu/faculty-staff/donald-w-viney

Don Viney on Teilhard de Chardin

in song and text

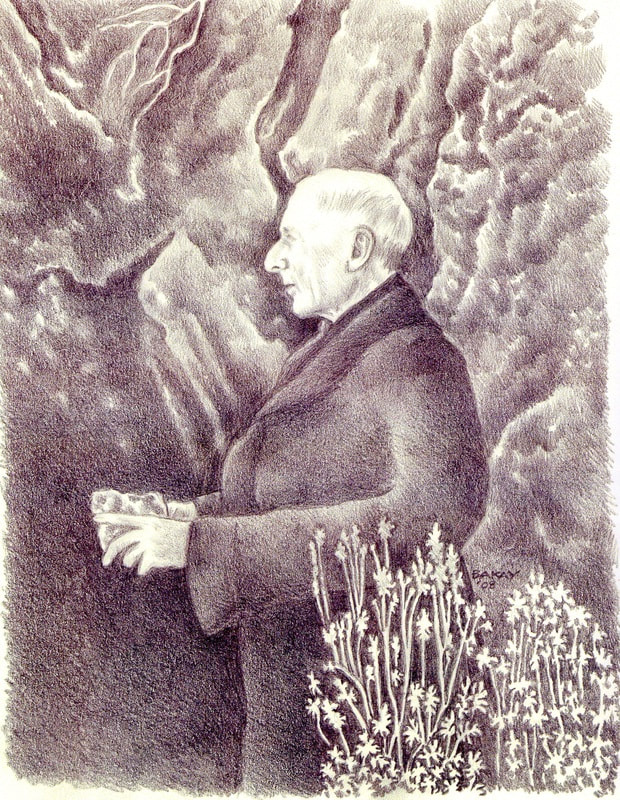

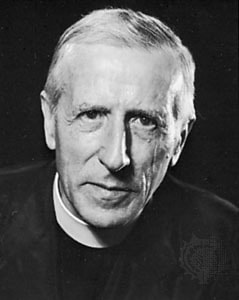

Few life stories can match that of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881-1955) for drama, passion, and intellectual ferment. The piety of his Catholic upbringing along with an early interest in geology set him on a collision course with the Church of his time but also presented an opportunity for creative transformation within the religious community as a whole. A Jesuit priest, a decorated veteran of World War I, and a distinguished scientist, Teilhard lived through some of the great crises of the twentieth century. Best known in his lifetime as a member of the team that discovered Peking Man and as the priest who embraced evolution, he was ever restless to convey his vision of cosmogenesis, the creative unfolding of the universe. For Teilhard, the physical universe, permeated to its most elementary elements by “the within” of experience, crossed the threshold of thought in human evolution and is destined to converge on a supremely personal “Omega Point.”

Teilhard’s religious superiors never permitted him to publish anything but strictly scientific articles, so he shared his vision through “clandestins”—as they were called—that he distributed in mimeographed form. Only after his death were these published, thanks to the efforts of Jeanne Mortier who volunteered her services as Teilhard’s secretary. Published in thirteen volumes between 1955 and 1976, the “clandestins” represent about a third of his oeuvres—the other two thirds being his extensive correspondence and his collected scientific articles. As witness to the importance of these volumes, Mortier assembled a thirty-two member scientific committee and a twenty-one member general committee; the names of the people on these committees, published in each of the French editions, includes numerous distinguished figures of French science and letters.

Teilhard’s posthumously published work created a sensation in scientific, religious, and philosophical circles. As Teilhard’s works were being published, the spirit of aggiornamento gripped the Church and Vatican II was in session. While Teilhard remained a theological outsider, the Church softened its opposition to evolutionary thinking; indeed, forty-six years after Teilhard’s death Pope John Paul II used Teilhardian language to declare evolution to be more than a hypothesis, but a theory confirmed by all of the deliverances of science. Moreover, many within the Church and outside of it took inspiration from the Teilhardian vision of a cosmos in the making. The biologist and anthropologist, David Sloan Wilson maintains that Teilhard was, in some respects, ahead of his time, both in terms of his science and his spirituality; says Wilson, “Let his scientific flame burn brightly again!” (Wilson, The Neighborhood Project, New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2011, p. 120).

Teilhard’s works secured his reputation as a world-class thinker and visionary. To be sure, from the beginning, some religious writers as well as a couple of well-known scientists questioned the value of his thought. Teilhard anticipated that he would be criticized as offering, on the one hand, something less than religious orthodoxy (or even something heretical) and, on the other hand, something more than science (or even something opposed to it). Doubtless, he would have refined or revised his ideas in light of this feedback, as he did before the works were published. It is unlikely, however, that he would have considered himself refuted. After all, Teilhard advocated, above all, a way of seeing the world, a new perspective that invites one to transcend disciplinary boundaries by considering humanity not as an anomalous branch on an evolutionary bush but as the shoot of an evolutionary tree through which is most visible the inner workings of the cosmos, divinely transformed at its heart.

I take the words of “Teilhard’s Fire,” in part, from a 1934 essay that Teilhard wrote as he was struggling with his feelings for his close friend Lucille Swan whose love he never returned in the ways she desired. The essay ends with words that have gained a wide circulation: “The day will come when, after mastering the ether, the winds, gravitation, we will capture for God the energies of love.—And then, for a second time in the history of the world, Man will have discovered Fire.” I adapted these lines, in both their original French and in translation, for the song. Another Teilhardian phrase that I use in the song is “union differentiates” (l’union différencie), which Teilhard calls a “universal law” (une règle universelle). For Teilhard, true love unites in such a way as to augment rather than to diminish the personalities of those caught in its Fire. Omega, of which Teilhard sometimes whispered, is God considered as the lure to unification with others and with creation itself in what Teilhard called “the divine milieu”—a present reality and a future promise.

In 1927, Teilhard wrote to Ida Treat that he wished he could translate his vision into music. My aim is not so audacious, although I hope that something of Teilhard survives in my composition beyond the words themselves.

-- Donald Viney

Teilhard’s religious superiors never permitted him to publish anything but strictly scientific articles, so he shared his vision through “clandestins”—as they were called—that he distributed in mimeographed form. Only after his death were these published, thanks to the efforts of Jeanne Mortier who volunteered her services as Teilhard’s secretary. Published in thirteen volumes between 1955 and 1976, the “clandestins” represent about a third of his oeuvres—the other two thirds being his extensive correspondence and his collected scientific articles. As witness to the importance of these volumes, Mortier assembled a thirty-two member scientific committee and a twenty-one member general committee; the names of the people on these committees, published in each of the French editions, includes numerous distinguished figures of French science and letters.

Teilhard’s posthumously published work created a sensation in scientific, religious, and philosophical circles. As Teilhard’s works were being published, the spirit of aggiornamento gripped the Church and Vatican II was in session. While Teilhard remained a theological outsider, the Church softened its opposition to evolutionary thinking; indeed, forty-six years after Teilhard’s death Pope John Paul II used Teilhardian language to declare evolution to be more than a hypothesis, but a theory confirmed by all of the deliverances of science. Moreover, many within the Church and outside of it took inspiration from the Teilhardian vision of a cosmos in the making. The biologist and anthropologist, David Sloan Wilson maintains that Teilhard was, in some respects, ahead of his time, both in terms of his science and his spirituality; says Wilson, “Let his scientific flame burn brightly again!” (Wilson, The Neighborhood Project, New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2011, p. 120).

Teilhard’s works secured his reputation as a world-class thinker and visionary. To be sure, from the beginning, some religious writers as well as a couple of well-known scientists questioned the value of his thought. Teilhard anticipated that he would be criticized as offering, on the one hand, something less than religious orthodoxy (or even something heretical) and, on the other hand, something more than science (or even something opposed to it). Doubtless, he would have refined or revised his ideas in light of this feedback, as he did before the works were published. It is unlikely, however, that he would have considered himself refuted. After all, Teilhard advocated, above all, a way of seeing the world, a new perspective that invites one to transcend disciplinary boundaries by considering humanity not as an anomalous branch on an evolutionary bush but as the shoot of an evolutionary tree through which is most visible the inner workings of the cosmos, divinely transformed at its heart.

I take the words of “Teilhard’s Fire,” in part, from a 1934 essay that Teilhard wrote as he was struggling with his feelings for his close friend Lucille Swan whose love he never returned in the ways she desired. The essay ends with words that have gained a wide circulation: “The day will come when, after mastering the ether, the winds, gravitation, we will capture for God the energies of love.—And then, for a second time in the history of the world, Man will have discovered Fire.” I adapted these lines, in both their original French and in translation, for the song. Another Teilhardian phrase that I use in the song is “union differentiates” (l’union différencie), which Teilhard calls a “universal law” (une règle universelle). For Teilhard, true love unites in such a way as to augment rather than to diminish the personalities of those caught in its Fire. Omega, of which Teilhard sometimes whispered, is God considered as the lure to unification with others and with creation itself in what Teilhard called “the divine milieu”—a present reality and a future promise.

In 1927, Teilhard wrote to Ida Treat that he wished he could translate his vision into music. My aim is not so audacious, although I hope that something of Teilhard survives in my composition beyond the words themselves.

-- Donald Viney

Lyrics to the Song

Come the day, when mastering

The winds, the tides, and space,

Gravity itself within our power.

We will tap, release, for God,

Love’s energies entire,

Such, our hope

and our most beauteous hour.

And then, for a second time,

In the history of the world,

We’ll have once again

Discovered fire.

As sun is scattered in the rain

Just so is love divine:

No two droplets quite the same

Yet in union shine.

Quelque jour, après l’espace,

Les vents et les marées,

Et même la gravitation,

Nous capterons, pour Dieu,

Les énergies de l’amour.

C’est l’étoile de nos espérances.

Et alors, une deuxième fois

Dans l’histoire du Monde,

Nous aurons encore trouvé le Feu.

L’amour divin aura grandi

En nous, et par lequel

L’union différencie--

Une règle universelle.

And then, for a second time,

In the history of the world,

We’ll have once again

discovered fire.

* “Teilhard” is pronounced “Tay-yar.” The images of the lyrics are drawn, more or less directly, from the Priest-Scientist, Teilhard de Chardin (1881-1955). « Quelque jour, après l’éther, les vents, les marées, la gravitation, nous capterons, pour Dieu, les énergies de l’amour.—Et alors, une deuxième fois dans l’histoire du Monde, l’Homme aura trouvé le Feu ». Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, « L’Evolution de la Chasteté, » (1934), Les Directions de l’Avenir (Paris : Éditions de Seuil, 1973), p. 92. Translation : The day will come when, after mastering the ether, the winds, gravitation, we will capture for God the energies of love.—And then, for a second time in the history of the world, Man will have discovered Fire.

« En n’importe quel domaine . . . l’Union différencie. Les parties se perfectionnent et s’achèvent dans tout ensemble organisé. C’est pour avoir négligé cette règle universelle que tant de Panthéismes nous ont égarés dans le culte d’un Grand Tout où les individus étaient censés se perdre comme une goutte d’eau, se dissoudre comme un grain de sel, dans la mer ». Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Le Phénomène humain (Paris : Éditions de Seuil, 1955), p. 291. Translation: “In whatever domain . . . Union differentiates. In every organized whole the parts perfect and fulfill themselves. By failing to grasp this universal law of union, so many kinds of pantheism have led us astray in the worship of a great Whole in which individuals were supposed to become lost like a drop of water, dissolved like a grain of salt, in the sea.” Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, The Human Phenomenon, translated by Sarah Appleton-Weber (Brighton and Portland: Sussex Academic Press, 1999), p. 186.

« En n’importe quel domaine . . . l’Union différencie. Les parties se perfectionnent et s’achèvent dans tout ensemble organisé. C’est pour avoir négligé cette règle universelle que tant de Panthéismes nous ont égarés dans le culte d’un Grand Tout où les individus étaient censés se perdre comme une goutte d’eau, se dissoudre comme un grain de sel, dans la mer ». Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Le Phénomène humain (Paris : Éditions de Seuil, 1955), p. 291. Translation: “In whatever domain . . . Union differentiates. In every organized whole the parts perfect and fulfill themselves. By failing to grasp this universal law of union, so many kinds of pantheism have led us astray in the worship of a great Whole in which individuals were supposed to become lost like a drop of water, dissolved like a grain of salt, in the sea.” Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, The Human Phenomenon, translated by Sarah Appleton-Weber (Brighton and Portland: Sussex Academic Press, 1999), p. 186.

More from Don Viney

music, influences, and ideas

A Sample of Don's MusicNote: La dernière page (the last page) refers to the last page that Jules Lequyer wrote which is often published with his writings and even as a separate pamphlet. Scroll down and find an English version of this song on Youtube.

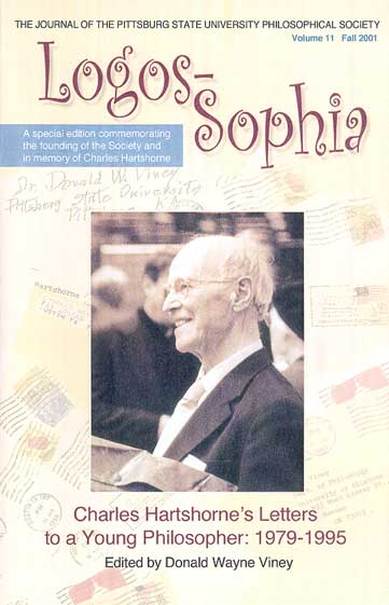

Philosophy after Hartshorne

Excerpt from Don Viney's Philosophy after Hartshorne "Process metaphysics, whether it is Hartshorne’s or Whitehead’s, repudiates both physicalism (or materialism) and dualism. The shared doctrine of physicalism and dualism is that some metaphysically basic parts of the universe -- let us use the neutral term "monads" -- are wholly insentient, wholly lacking in mind-like qualities. Hartshorne denies this. Every monad is a psychophysical whole -- in this philosophy. no res vera is entirely devoid of a psychic (i.e., mind-like) quality. Hartshorne called this view psychicalism. In earlier writings he used the word panpsychism to express this idea, but he came to believe that this term too easily lends itself to confusing his theory with simple animism that attributes to every real thing -- chairs or rocks, for instance -- feeling or consciousness. Hartshorne reasons that, "Feeling can be everywhere even though many things do not feel, somewhat as vibration can be everywhere even though chairs do not vibrate (only their micro-constituents do)" (Zero 134). The criterion by which Hartshorne distinguishes what does and does not have feeling is, "what acts as one feels as one." A plant may seem to meet this criterion, but Hartshorne argues that it is the cells of the plant that are most active. As he says in "God as Composer-Director": "Even a tree’s growth is shorthand for the self-multiplication of its cells. Animals with central nervous systems are the only many-celled individuals we perceive that act integrally and even they do not do so in deep sleep." With Leibniz, Hartshorne maintains that some organisms are governed by a "dominant entelechy" that serves as a center of perception and activity (Monadology # 70); other organisms, and all inorganic wholes (e.g. chemical compounds and minerals), have insufficient organizational complexity to act or feel "as one. Hartshorne tenaciously defended psychicalism throughout his career, even as he realized that his was the minority position, as it remains to this day. But when did majorities ever intimidate Hartshorne, especially when he saw evidence of genius on his side? As he says in the paper on Troland: "I regard this as an elite minority and am not abashed by the majority on this point. For I fail to find careful reasoning on the majority side and there is much careful reasoning on my side, from Leibniz to Troland, Whitehead, Wright, and some others." One may accuse Hartshorne of boasting, but there is no gainsaying that recent discussions in the philosophy of mind often ignore the very figures that Hartshorne holds to have developed the most intelligible form of the doctrine; in short, panpsychism is discussed but psychicalism is not (e.g. Nagel 181-95; Chalmers 293-99; McGinn 95-101). Griffin is a refreshing exception to the rule (Unsnarling 92-98). In the final analysis Hartshorne uses an organic model to express God’s relation to the world. He appropriates and updates Plato’s World-Soul analogy. For Hartshorne, God is related to the universe in a manner that is similar to the way that a person is related to the cells of his or her body. Hartshorne insists that, "A body is, in the human case, no merely single thing, but a vast society of society of perhaps two hundred thousand kinds of cells. The mind-body relation is then emphatically a one-many relation, not a one-one relation" ("Postscript" 317). Our own feelings cannot be entirely separated from the feelings of the cells: "Hurt my cells and you hurt me" ("Postscript" 317). In a somewhat similar fashion, God is affected by what affects us. One difference between God and all non-divine individuals is that God knows each "cell" of the divine body in a perfectly distinct fashion whereas others experience their cells en masse, much as one sees the green of the grass but not each blade. This vagueness in the perceptions of our own bodies is the reason, according to Hartshorne, that the mind-body relationship is often mistaken as a relationship between two fundamentally different substances. Hartshorne also argues that the divine body unlike a merely localized body has no external environment. All of the "parts" of God are internal to the divine body. The experiences of the creatures, and whatever values they have, become immortalized in the memory of God. Yet, no creature can surpass God since each element of the divine body has a beginning and an end, but God is without beginning or end. Thus, Hartshorne refers to God as the "self-surpassing surpasser of all" (Divine Relativity 20). -- Donald Wayne Viney, Philosophy after Hartshorne Charles Hartshorne's Creative Experiencing: A Philosophy of Freedom

"Charles Hartshorne, one of the premier metaphysicians of the twentieth century, surmised that Creative Experiencing: A Philosophy of Freedom made his contribution to technical philosophy essentially complete. Found among his papers, this book combines five chapters published here for the first time with revisions and expansions of previously published material. Hartshorne articulates and defends his “neoclassical metaphysics” as an enterprise related to but independent of empirical science, addressing a variety of topics, including the problem of other minds (including nonhuman ones), the competencies of science, the nature of God, the meaning of modal terms, the ontological status of universals, and the metaphysical grounding of political freedom. While Hartshorne is widely known as a process philosopher, Creative Experiencing also shows him in dialogue with the wider currents of both analytic philosophy and phenomenology. The book includes his clearest account of his appropriation of phenomenology, the most succinct presentation of his analysis of time’s asymmetry and its relation to causality, and his fullest statement concerning the meaning of future tense statements."

Source: SUNY Press Jules Lequyer"Jean Grenier remarked that the philosophy of Jules Lequyer (1814-1862)—also spelled Lequier—is nothing but a serious meditation on the word “create.” With some justification he has been called “the French Kierkegaard,” and existentialists note anticipations of their ideas in Lequyer’s work. He wrote, “To act is always to act with audacity and passion.” In Search for a First Truth, he posits freedom as the necessary condition of both morality and knowledge. Lequyer does not attempt to prove the reality of freedom, but he believes that the experience of freedom—what he calls a “presentiment” of freedom—indicates that freedom is a creative act, an act that brings something into being that, before the act, existed only as a possibility.

Lequyer argues that a free creature is partly self-creative. One’s acts of freedom determine who one will become. In addition to self-creation, one’s acts of freedom create something new in the world, and in other persons. Thus, each person is partly creative of the world and of other persons. Lequyer speaks of the free individual as a “dependent independence.” The free creature does not bring itself into existence; however, once in existence, its decisions create “new modes of being.” These reflections on freedom are extended to theology, for Lequyer was a deeply religious man. Lequyer speaks of “God, who created me creator of myself.” Moreover, the free creature’s decisions bring something new into existence for God, if only the decisions themselves. In contrast to traditional theology, Lequyer maintained that a free individual’s decisions have effects on God. In Lequyer’s words, the free decision “makes a spot on the absolute that destroys the absolute.” Lequyer gives an extended treatment of these issues in his Dialogue of the Predestinate and the Reprobate. There he argues that absolute divine foreknowledge is incompatible with human freedom. Lequyer says, “man deliberates and God waits.” According to Lequyer, God’s knowledge is perfect in the sense that it encompasses the extent to which the future is open or closed for each individual. Lequyer takes up the question of God’s grace and free will in his “biblical narrative” Abel and Abel. Identical twins are tested as to their reactions to God arbitrarily favoring one over the other. God’s grace is a call for them to use their freedom in love for their twin brother. The fate of each brother is determined by how they used or misused their freedom in the test. Not widely known in English speaking circles, Lequyer nevertheless had an influence on philosophy that is disproportionate to the widespread ignorance of his name. In France, Charles Renouvier and Jean-Paul Sartre quoted Lequyer’s phrase “TO MAKE, and in making, TO MAKE ONESELF” as a summary statement of, respectively, personalism and existentialism. In the United States, William James’s ideas about free will owe a great deal to Lequyer’s influence. Charles Hartshorne first brought Lequyer’s work to the attention of Anglophones and noted his parallels with process philosophy. More recently, philosophers have realized that, in speaking of “God, who created me creator of myself,” Lequyer anticipated the theology of open theism." -- Don Viney |

A Word about Music

"Two of the blessings of my life are the joy I take in singing and the knowledge that there are people who take pleasure in listening to me sing. I also compose music and occasionally write lyrics set to tunes that others have written. I began university as a music major but eventually switched to something easier: philosophy. I am, by profession, a philosophy professor, so I do not pretend to compose or perform as a professional. I was fortunate to be raised by parents who valued music. My mother was an expert pianist and a fine singer who cherished close harmonies. My father also loves music and sings well. In their first years of marriage, they were hired by churches as a music director and pianist. Neither chose music as a career, but they taught me to think of music as integral to life and they nurtured the seeds of talent that they found in me. In one form or another, our home was filled with music of many kinds—choral, instrumental, symphonic, operatic, gospel, folk, pop, and, of course, Broadway musicals. There is some truth in the remark of one of my colleagues that I grew up in a musical. I did not fully appreciate the power of music until a few years ago. My life was turned upside down by a traumatic divorce. One day, alone in the house with only my pets as company, I vented my anger and frustration by screaming at the top of my lungs. The poor animals were frightened and I damaged my voice to such an extent that I did not think that it would recover. A musician friend of mine counselled patience, saying my voice would heal. She was correct. There came a day when I sang with such joy as I had never known—it didn’t hurt that I had found new love. From that day to the present, the singing of music is no longer, for me, a question of mere performance but of a highly individual union with the sounds, the emotions, and the thoughts that music can convey. I say “individual,” but I am in love with the wisdom of harmonies. One cannot sing Handel’s “Hallelujah Chorus” by oneself. As Teilhard de Chardin was fond of saying in speaking of love, “Union differentiates.” Music is not the only way of achieving that sort of differentiating union, but I rejoice that it is open to me and that it is an opening for me to share with others" -- Don Viney Whitehead's Legacy

|