The Beautiful Smallness of God

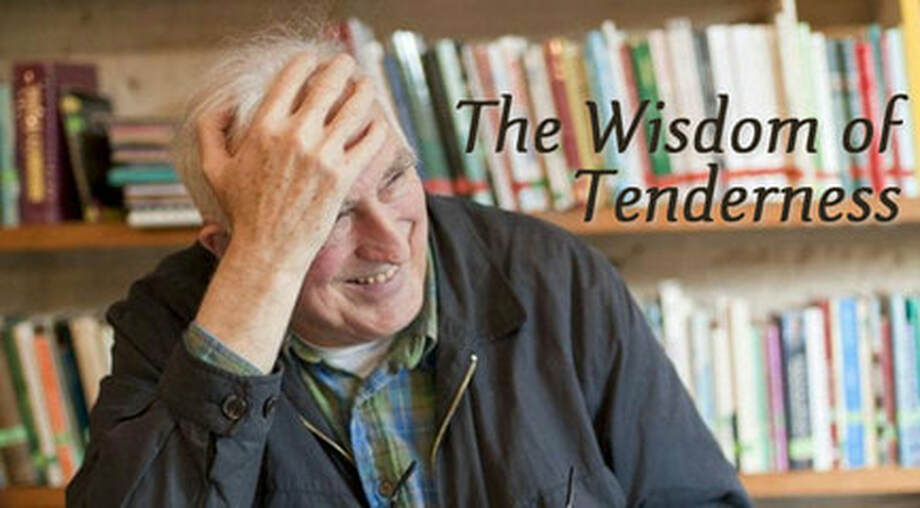

Learning from Jean Vanier about

Christianity and the Wisdom of Tenderness

Krista Tippett's Interview with Jean Vanier

Whatever their gifts on their limitations, people are all bound together in a common humanity. Everyone is of unique and sacred

value, and everyone has the same dignity and the same rights. The fundamental rights of each person include the rights to life, to care, to a home, to education and to work. Also, since the deepest need of a human being is to love and to be loved, each person has a right to friendship, to communion and to a spiritual life.

-- Jean Vanier

About Jean Vanier (from Spirituality and Practice)

Early in the morning on May 7, 2019, Jean Vanier slipped away from the human form in which he'd given such great solace and hope to people, especially those suffering from developmental disabilities. He will be greatly missed for his genuine humility, profound leadership, and values drawn directly from the Beatitudes — values that bless the poor and the poor in spirit. He has been an inspiration to all of us at Spirituality & Practice for decades and will be greatly missed, even while we continue to benefit from his teachings and a felt sense of his ever-living presence.

Vanier was born in Geneva while his father, the 19th Governor General of Canada, was on diplomatic service in Switzerland. During his childhood, his family lived in Canada, England, and France, fleeing Paris right before occupation by the Nazis during World War II. In 1945, Vanier and his mother assisted victims of a concentration camp; their suffering moved the Vaniers profoundly. In 1964, at age 36, Vanier dove even deeper into his true calling by moving in with two men with intellectual disabilities who had been living in an institution. Their home became the first L'Arche community.

It was followed by an international federation of communities in more than 37 countries, welcoming people of all faiths, abilities, and traditions. Together with Marie-Hélène Mathieu, Vanier subsequently founded Faith and Light, which also works with and for people with disabilities around the world. He has received numerous awards, including the French Legion of Honor and the Templeton Prize.

After becoming aware of the plight of people with developmental disabilities who were institutionalized — marginalized, depressed, and alone — Vanier opened his home to them in what was to become his lifelong ministry. "People with disabilities have called forth the child in me," he observed. "They have taught us all in L'Arche how to rest in love and mutual caring, how to celebrate life and also celebrate death, to speak about death, to accompany people who are dying."

Jean Vanier's radical view of the spiritual practice of hospitality took within its embrace strangers, outcasts, those who are different, the shadow sides of ourselves, and our enemies who have their own burden of pain. Loving, forgiving, and opening our hearts, he believed, is an alternative to the world's divisions and weapons.

-- Frederic Brussat and Patricia Campbell Carlson in Spirituality and Practice

Vanier was born in Geneva while his father, the 19th Governor General of Canada, was on diplomatic service in Switzerland. During his childhood, his family lived in Canada, England, and France, fleeing Paris right before occupation by the Nazis during World War II. In 1945, Vanier and his mother assisted victims of a concentration camp; their suffering moved the Vaniers profoundly. In 1964, at age 36, Vanier dove even deeper into his true calling by moving in with two men with intellectual disabilities who had been living in an institution. Their home became the first L'Arche community.

It was followed by an international federation of communities in more than 37 countries, welcoming people of all faiths, abilities, and traditions. Together with Marie-Hélène Mathieu, Vanier subsequently founded Faith and Light, which also works with and for people with disabilities around the world. He has received numerous awards, including the French Legion of Honor and the Templeton Prize.

After becoming aware of the plight of people with developmental disabilities who were institutionalized — marginalized, depressed, and alone — Vanier opened his home to them in what was to become his lifelong ministry. "People with disabilities have called forth the child in me," he observed. "They have taught us all in L'Arche how to rest in love and mutual caring, how to celebrate life and also celebrate death, to speak about death, to accompany people who are dying."

Jean Vanier's radical view of the spiritual practice of hospitality took within its embrace strangers, outcasts, those who are different, the shadow sides of ourselves, and our enemies who have their own burden of pain. Loving, forgiving, and opening our hearts, he believed, is an alternative to the world's divisions and weapons.

-- Frederic Brussat and Patricia Campbell Carlson in Spirituality and Practice

The Beautiful Smallness of God

Several years ago a good friend of mine -- I will call her Jane -- became a Christian. She had grown up in a secular environment and was very suspicious of anything close to "organized religion." She still is.

But she listened to the interview with Jean Vanier from On Being with Krista Tippett, and she heard something beautiful that rang true to her. It was not the truth of theology but rather the truth of experience. She calls it the wisdom of tenderness. She left secularism and decided to walk with Jesus. She's still walking.

Jane is not alone. This single interview has changed many lives for the better. It has helped me realize the limited value of theology, including my own. Vanier speaks of the primacy of experience over ideas. I'm with him. When we get too lost in our heads, we lose what really matters in life: to love and be loved. Love is so much bigger than theology. Or, to say it better, so much smaller. Let me explain.

Smallness and Beauty

Jane is not a Christian exclusivist. Jean Vanier talks about learning from a Muslim friend and a Hindu friend, and Jane likes this. She is spacious, too.

Still, Jane is a little friend of Jesus. Hers is not an imperial Christianity. It is not about winning converts. It is counter-cultural and power-relinquishing, gentle in heart and body. It is about downward mobility not upward mobility, about descending into the depths of the broken human body. It is about joy.

Maybe this is what Christianity is about. Maybe Christianity begins with the experience of a God who the very opposite of untouchability, because touched every time we love others and are loved by them. Maybe the good news is that God is closer than we might otherwise imagine, disarmingly close because present in the other person and in our own hearts.

I ask Jane if she believes in God. She says: I believe in tenderness. I ask her if tenderness is high and mighty or small and beautiful. She says small and beautiful. I ask her what she likes about Jesus and she says vulnerability. I asked her if Christianity is about pleasure or obligation and she says pleasure. It's all about the satisfaction of a desire to love and be loved.

I tell her that some Christians might say her God is too small and she says maybe their God is too big. I think of Whitehead who said that we wrongly render unto God that which belongs to Caesar and who proposes instead that we render unto God what which belongs to Jesus. Jane would add that we render unto God that which belongs to those Jesus touched: the disabled.

I think of a Buddhist student of mine, Vivian Dong, who once said that the only God she could believe in would have to be tiny enough to fit behind the eyes of each person. I think Jane and Vivian would like each other.

-- Jay McDaniel

But she listened to the interview with Jean Vanier from On Being with Krista Tippett, and she heard something beautiful that rang true to her. It was not the truth of theology but rather the truth of experience. She calls it the wisdom of tenderness. She left secularism and decided to walk with Jesus. She's still walking.

Jane is not alone. This single interview has changed many lives for the better. It has helped me realize the limited value of theology, including my own. Vanier speaks of the primacy of experience over ideas. I'm with him. When we get too lost in our heads, we lose what really matters in life: to love and be loved. Love is so much bigger than theology. Or, to say it better, so much smaller. Let me explain.

Smallness and Beauty

Jane is not a Christian exclusivist. Jean Vanier talks about learning from a Muslim friend and a Hindu friend, and Jane likes this. She is spacious, too.

Still, Jane is a little friend of Jesus. Hers is not an imperial Christianity. It is not about winning converts. It is counter-cultural and power-relinquishing, gentle in heart and body. It is about downward mobility not upward mobility, about descending into the depths of the broken human body. It is about joy.

Maybe this is what Christianity is about. Maybe Christianity begins with the experience of a God who the very opposite of untouchability, because touched every time we love others and are loved by them. Maybe the good news is that God is closer than we might otherwise imagine, disarmingly close because present in the other person and in our own hearts.

I ask Jane if she believes in God. She says: I believe in tenderness. I ask her if tenderness is high and mighty or small and beautiful. She says small and beautiful. I ask her what she likes about Jesus and she says vulnerability. I asked her if Christianity is about pleasure or obligation and she says pleasure. It's all about the satisfaction of a desire to love and be loved.

I tell her that some Christians might say her God is too small and she says maybe their God is too big. I think of Whitehead who said that we wrongly render unto God that which belongs to Caesar and who proposes instead that we render unto God what which belongs to Jesus. Jane would add that we render unto God that which belongs to those Jesus touched: the disabled.

I think of a Buddhist student of mine, Vivian Dong, who once said that the only God she could believe in would have to be tiny enough to fit behind the eyes of each person. I think Jane and Vivian would like each other.

-- Jay McDaniel