- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

Queerly Good News

Even without an overstated point of view, The Gospel of Eureka offers queerly good news through its invitation to question-asking. The place might not be perfect, but it’s full of faithful folks trying to figure out what freedom means for all of them. Ultimately, its example of how those who might not see eye to eye can still see heart to heart suggests a model for reaching across the aisle while still staying firmly and fabulously true to one’s own glittery spirit.

-- Micah Bucey

-- Micah Bucey

The Gospel of Eureka

Directed by Donal Mosher, Michael Palmieri

Reposted from Spirituality and Faith

Film Review by Micah Bucey

Outside one of the churches in Eureka Springs, Arkansas, a billboard reads: “Too Hot to Change Sign. Sin bad. Jesus good.” This kind of shorthand faithfulness runs deep throughout both this tiny community (population 2,073) and The Gospel of Eureka, Donal Mosher and Michael Palmieri’s lovely and loving documentary. It seems for all of Eureka Springs’ inhabitants, faith can be a simple thing, even if other aspects of their life together can get a bit complicated.

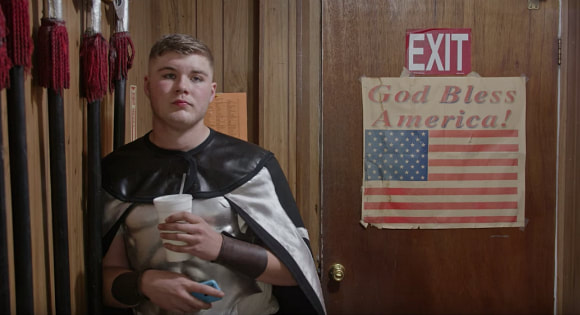

Eureka Springs has a troubling and troubled history, not the least of which is the fact that its main attraction, a Passion Play that has been performed for decades and which still utilizes the talents of dozens of community members, was founded by notoriously anti-Semitic and racist evangelist Gerald L.K. Smith. Christian audiences still come from miles around to see a made-up, fake-blood-spattered, white Jesus perform crackerjack miracles, triumphantly enter Jerusalem, suffer crucifixion, and then resurrect and fly into the air (with the help of some strong wires). And overlooking all of this drama is the glaringly white “Christ of the Ozarks,” a 1966 Smith statue commission that stands regally atop Magnetic Mountain, at 65.5 feet tall.

In the midst of the current U.S. culture wars, the sight of these overtly Christian landmarks might first define Eureka Springs as an exclusionary space steeped in the sort of evangelical and fundamentalist theology that historically dismisses the queer experience as antithetical to true faithfulness. But Eureka Springs isn’t that easy a target. Just down the road is another spectacle, Eureka Live, a drag bar owned by a longtime gay couple, Gregory Lee Keating and Walter Burrell, who have their own faithful following and their own unique sense of resurrective, theatrical flair.

With these apparently oppositional attractions at the center, The Gospel of Eureka might at first seem most interested in revealing how the country’s culture wars manifest in the microcosm of one tiny petri dish of a town, but these big-hearted filmmakers are far more intent on spotting connections and grace. As Trans performance artist Mx. Justin Vivian Bond’s gravelly voice narrates the proceedings, the camera is content to simply observe and appreciate, moving from campy but sincere paintings of Jesus to campy and outlandish drag performances, from scenes of Biblical brutality to scenes of friendly fabulosity.

As more and more personalities are introduced, including the devout and proud son of a gay Dad who owns a Christian souvenir store and a Trans woman whose love for the town’s Passion Play is truly palpable, perspectives shift in queerly unexpected ways, showing how devotion and diversion can go hand-in-hand, uncovering the links between faith and freedom that keep Eureka Springs and its colorful personalities not only interesting, but ultimately inspiring. Most importantly, by refusing to seek villains among the town’s inhabitants, Mosher and Palmieri offer an inviting glimpse into the cracks within community that might possibly be filled with generous curiosity, instead of fearful hate.

Lest this all sound too simplistic and touchy-feely, no trite and pat solutions are suggested. Portraits of normal folks are simply shown side-by-side, everyday people in and out of their respective drag and roles, at church, at home, on the streets, some marveling at enacted scripture stories and some at awesome lip-synch performances. The most overtly linear storyline features the community’s fight over Non-Discrimination Ordinance 2223, aimed at protecting LGBTQ citizens of the town, and audiences will encounter both folks with whom they wholeheartedly agree and folks with whom they vehemently disagree. Eureka Springs is not paradise; it’s a place of possibility.

Even without an overstated point of view, The Gospel of Eureka offers queerly good news through its invitation to question-asking. The place might not be perfect, but it’s full of faithful folks trying to figure out what freedom means for all of them. Ultimately, its example of how those who might not see eye to eye can still see heart to heart suggests a model for reaching across the aisle while still staying firmly and fabulously true to one’s own glittery spirit.

Eureka Springs has a troubling and troubled history, not the least of which is the fact that its main attraction, a Passion Play that has been performed for decades and which still utilizes the talents of dozens of community members, was founded by notoriously anti-Semitic and racist evangelist Gerald L.K. Smith. Christian audiences still come from miles around to see a made-up, fake-blood-spattered, white Jesus perform crackerjack miracles, triumphantly enter Jerusalem, suffer crucifixion, and then resurrect and fly into the air (with the help of some strong wires). And overlooking all of this drama is the glaringly white “Christ of the Ozarks,” a 1966 Smith statue commission that stands regally atop Magnetic Mountain, at 65.5 feet tall.

In the midst of the current U.S. culture wars, the sight of these overtly Christian landmarks might first define Eureka Springs as an exclusionary space steeped in the sort of evangelical and fundamentalist theology that historically dismisses the queer experience as antithetical to true faithfulness. But Eureka Springs isn’t that easy a target. Just down the road is another spectacle, Eureka Live, a drag bar owned by a longtime gay couple, Gregory Lee Keating and Walter Burrell, who have their own faithful following and their own unique sense of resurrective, theatrical flair.

With these apparently oppositional attractions at the center, The Gospel of Eureka might at first seem most interested in revealing how the country’s culture wars manifest in the microcosm of one tiny petri dish of a town, but these big-hearted filmmakers are far more intent on spotting connections and grace. As Trans performance artist Mx. Justin Vivian Bond’s gravelly voice narrates the proceedings, the camera is content to simply observe and appreciate, moving from campy but sincere paintings of Jesus to campy and outlandish drag performances, from scenes of Biblical brutality to scenes of friendly fabulosity.

As more and more personalities are introduced, including the devout and proud son of a gay Dad who owns a Christian souvenir store and a Trans woman whose love for the town’s Passion Play is truly palpable, perspectives shift in queerly unexpected ways, showing how devotion and diversion can go hand-in-hand, uncovering the links between faith and freedom that keep Eureka Springs and its colorful personalities not only interesting, but ultimately inspiring. Most importantly, by refusing to seek villains among the town’s inhabitants, Mosher and Palmieri offer an inviting glimpse into the cracks within community that might possibly be filled with generous curiosity, instead of fearful hate.

Lest this all sound too simplistic and touchy-feely, no trite and pat solutions are suggested. Portraits of normal folks are simply shown side-by-side, everyday people in and out of their respective drag and roles, at church, at home, on the streets, some marveling at enacted scripture stories and some at awesome lip-synch performances. The most overtly linear storyline features the community’s fight over Non-Discrimination Ordinance 2223, aimed at protecting LGBTQ citizens of the town, and audiences will encounter both folks with whom they wholeheartedly agree and folks with whom they vehemently disagree. Eureka Springs is not paradise; it’s a place of possibility.

Even without an overstated point of view, The Gospel of Eureka offers queerly good news through its invitation to question-asking. The place might not be perfect, but it’s full of faithful folks trying to figure out what freedom means for all of them. Ultimately, its example of how those who might not see eye to eye can still see heart to heart suggests a model for reaching across the aisle while still staying firmly and fabulously true to one’s own glittery spirit.