The Grace of Trees

Process Theology for Tree People

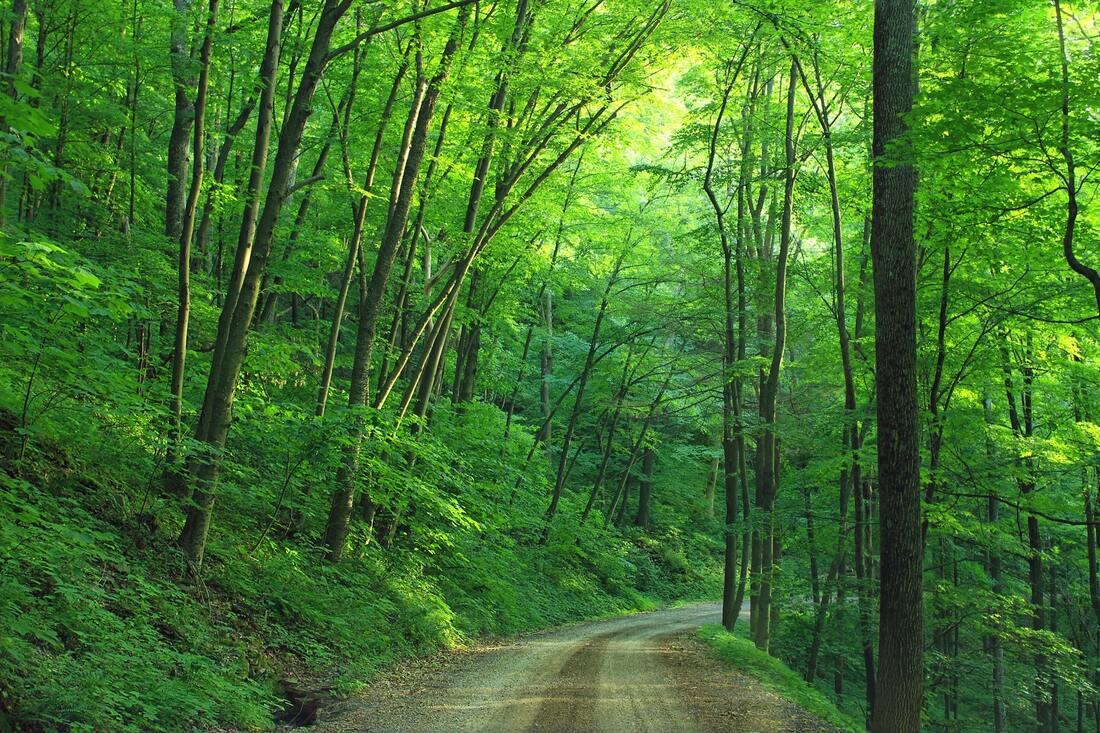

Tree people know the grace, the healing power, of trees. When they seek comfort or companionship, they turn to trees. When they want to be in touch with the deep and creative energies of life, they turn to trees. When they want to be encouraged and inspired, they turn to trees. Consider the poems by Kathleen Reeves at the bottom of this page. She is a tree person.

Tree people have their unique, tree-centered practices. They sit underneath trees, gaze lovingly at them, and touch them. They touch them by feeling their bark with their fingers, by wrapping their arms around them, and by climbing them. They also enjoy walking under tree canopies, feeling sheltered. The sense of being sheltered is part of the comfort of trees. Generally speaking, trees are non-anxious presences. The philosopher Whitehead speaks of God as a "fellow sufferer who understands." Tree people feel that, in some deep way, trees also understand. The older trees are grandmotherly sages, indeed pastoral counselors, in a sometimes crazy world. Kathleen Reeves speaks lovingly of Grandmother Sycamore.

Which makes sense. After all, the universe is a communion of subjects not a collection of objects. So we learn from Thomas Berry, process philosophers and theologians, indigenous traditions, Islamic Sufism, Kabbalistic Judaism, Hua-Yen Buddhism, the Bahá’í faith, and myriad other sources. The general idea is that every actuality in the universe has a kind of inwardness, an aliveness, a subjectivity, an insideness, a Buddha-nature. All actualities are concrescing subjects. Like trees, they communicate with one another and form societies. They exist through, not apart from, their relationships.

Trees and the cells that compose their bodies are among the many magnificent instances of this aliveness. Whether individual trees are concrescing subjects in their own right, or aggregate expressions of cellular subjects, is not important. What is important is that they are so powerful, dignified, and beautiful. And yet, to our joy, they are kin to us. They are not our servants, they are our hosts. We belong to a communion of subjects and they are among our oldest of relatives. Our grandmothers, our grandfathers, our uncles, our aunts. Thomas Berry and process theologians invite us to imagine the entire universe on the analogy of an interstellar forest: a wood-wide web of felt relationships. Wood-wide web is a phrase borrowed from Suzanne Simmard, scientist and author of Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest.

Process theologians invite us to think of the living unity of the universe as the Mother Tree of the universe as a whole. This Mother Tree would be a single, everlasting concrescence: the grandmotherly God who feels and responds to the whole in a mother tree way. She is connected to all the other trees, shares in their experiences, and provides nutrients (initial aims) to each and all. Some process theologians picture the Mother Tree on the analogy of an animal psyche: a conscious mind with feelings and aims of her own. She is a cosmic Person. Others picture her in more transpersonal ways: a connective tissue of love, for example. Either way is fine and some people vacillate between these two: the personal and transpersonal. The Mother Tree is not jealous.

Mother Tree or no Mother Tree, we find something beautiful, something sacred, through individual trees. This "finding something beautiful" is not merely intellectual or, for that matter, visual. It is tactile. We cannot really know trees, says Roland Faber, unless we touch them. Touching trees is a way of feeling their energy, their power, their inwardness. Trees bring us out of our heads and into our fingers.

This, then, is a process page for tree people, guided by lures for feeling from Carl Jung, Thomas Berry, Roland Faber, Jill Suttie, Cyndy Gilbert, Suzanne Simmard, Kathleeen Reeves, and the Druids. If you are a tree person, I hope the snippets of wisdom inspire you to develop further your own tree theology. That development, that creative imagination, is what the trees desire, and it is how we enter into further communion with, as Kathleen Reeves puts it, our sycamore grandmothers.

- Jay McDaniel, 11/5/2021

Tree people have their unique, tree-centered practices. They sit underneath trees, gaze lovingly at them, and touch them. They touch them by feeling their bark with their fingers, by wrapping their arms around them, and by climbing them. They also enjoy walking under tree canopies, feeling sheltered. The sense of being sheltered is part of the comfort of trees. Generally speaking, trees are non-anxious presences. The philosopher Whitehead speaks of God as a "fellow sufferer who understands." Tree people feel that, in some deep way, trees also understand. The older trees are grandmotherly sages, indeed pastoral counselors, in a sometimes crazy world. Kathleen Reeves speaks lovingly of Grandmother Sycamore.

Which makes sense. After all, the universe is a communion of subjects not a collection of objects. So we learn from Thomas Berry, process philosophers and theologians, indigenous traditions, Islamic Sufism, Kabbalistic Judaism, Hua-Yen Buddhism, the Bahá’í faith, and myriad other sources. The general idea is that every actuality in the universe has a kind of inwardness, an aliveness, a subjectivity, an insideness, a Buddha-nature. All actualities are concrescing subjects. Like trees, they communicate with one another and form societies. They exist through, not apart from, their relationships.

Trees and the cells that compose their bodies are among the many magnificent instances of this aliveness. Whether individual trees are concrescing subjects in their own right, or aggregate expressions of cellular subjects, is not important. What is important is that they are so powerful, dignified, and beautiful. And yet, to our joy, they are kin to us. They are not our servants, they are our hosts. We belong to a communion of subjects and they are among our oldest of relatives. Our grandmothers, our grandfathers, our uncles, our aunts. Thomas Berry and process theologians invite us to imagine the entire universe on the analogy of an interstellar forest: a wood-wide web of felt relationships. Wood-wide web is a phrase borrowed from Suzanne Simmard, scientist and author of Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest.

Process theologians invite us to think of the living unity of the universe as the Mother Tree of the universe as a whole. This Mother Tree would be a single, everlasting concrescence: the grandmotherly God who feels and responds to the whole in a mother tree way. She is connected to all the other trees, shares in their experiences, and provides nutrients (initial aims) to each and all. Some process theologians picture the Mother Tree on the analogy of an animal psyche: a conscious mind with feelings and aims of her own. She is a cosmic Person. Others picture her in more transpersonal ways: a connective tissue of love, for example. Either way is fine and some people vacillate between these two: the personal and transpersonal. The Mother Tree is not jealous.

Mother Tree or no Mother Tree, we find something beautiful, something sacred, through individual trees. This "finding something beautiful" is not merely intellectual or, for that matter, visual. It is tactile. We cannot really know trees, says Roland Faber, unless we touch them. Touching trees is a way of feeling their energy, their power, their inwardness. Trees bring us out of our heads and into our fingers.

This, then, is a process page for tree people, guided by lures for feeling from Carl Jung, Thomas Berry, Roland Faber, Jill Suttie, Cyndy Gilbert, Suzanne Simmard, Kathleeen Reeves, and the Druids. If you are a tree person, I hope the snippets of wisdom inspire you to develop further your own tree theology. That development, that creative imagination, is what the trees desire, and it is how we enter into further communion with, as Kathleen Reeves puts it, our sycamore grandmothers.

- Jay McDaniel, 11/5/2021