- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

A Different Kind of Process Philosophy

The Kyoto School of Japanese Buddhist Philosophy

grounded in Emptiness not God

The purpose of this page is to introduce Western readers to a different kind of Process Philosophy: one that is grounded in Emptiness not God. I am speaking of what is often called the Kyoto School of Japanese Buddhist Philosophy.

New to it? Two excellent websites for learning about it are: The Kyoto School of Philosophy and The Way of Emptiness. Both are created and curated by an independent scholar and Zen practitioner, Nicole Bea Pastoukoff. Her websites have essays and articles on three figures in the Kyoto school: Nishida Kitaro, Nishitani Keiji, and Ueda Shizuteru plus much more: essays on Theravada, Indian Mahayana, East Asian Buddhism, Japanese Buddhism, and Contemporary Buddhist Philosophy. The Way of Emptiness is especially remarkable in its scope and depth. With her permission, Open Horizons will be publishing more of her material. This page, however, offers three essays from The Kyoto School website.

My thesis is simple. It is that the Kyoto School offers a different kind of process philosophy. To be sure, it builds upon process themes such as inter-becoming, the primacy of moments of experience, the mutual immanence of all things, and the idea that the process of experiencing the world, as undertaken and undergone in human life, has no separate experiencer. But there is one more theme that it also builds upon, namely that the ultimate reality is Emptiness not God. Or, as Whitehead might put it, Creativity not God. An important feature of process philosophy as influenced by Alfred North Whitehead is that it distinguishes the ultimate reality of Creativity from the God of love, affirming both.

Of course everything depends on what is meant by process philosophy. For a brief overview of the process perspective, see The Twenty Key Ideas of Process Thought on home page of Open Horizons. Some ideas will sound very Buddhist: we live in a universe of mutual becoming in which all things are present in all of things; there is something like inwardness or subjectivity in each and every actuality; reality itself is pure becoming or process. For process thinkers, these ideas are important, not simply because they are true to the nature of things, but because, if taken to heart, they can help create a better world. The four aims of the process movement are to help people become more whole as individuals; to foster compassionate and just communities that are good for people, other animals, and the earth; to protect and care for the planet as a whole; and to encourage holistic ways of thinking that recognize the interconnectedness of all things, the intrinsic value of life, and the processive nature of reality.

Many process philosophers and theologians from the West and influenced by Abrahamic traditions add that holistic thinking includes the recognition of a divine source or companion, God, who embraces the whole and lures creation toward beauty, diversity, and goodness. Often they naturally and understandably assume that a process-relational point view includes a belief in God – not an authoritarian God of coercion, but a loving God of persuasion. A God who is not separate from the universe but who is the very mind of the universe. Some call it pan-en-theism: everything in God even as God is more than everything.

However, there are some for whom this belief in God, even the process God, is not religiously compelling. They are drawn toward alternative process perspective which emphasize the ultimacy of interconnectedness or the ultimacy of an energy, consciousness, or creativity which, as they see things, is truly the ground of all things.

This is where the Kyoto School of Buddhist philosophy can make more sense. It does indeed speak of a ground to all things, but also emphasizes that it is a groundless ground. It is not a creator or even a generative source; it is not a substance or a thing; it is not a creator or agent. Nishida speaks of it as the field of force by virtue of which all things as they are in themselves gather themselves into one: the field of the possibility of the world (RN 150-51), It is best understood, not when believed in but rather when directly experienced. And yet even this experience is easily misrepresented. It is not a mystical awakening to something deeper or higher than the world around us, it is an awakening to a kind of emptiness that is coincident with the world, not separated as a transcendent object.

For process thinkers, this Emptiness akin to the Creativity of which Whitehead speaks. This Creativity is not God. It is a groundless ground of which even God is an expression along with everything else in the universe. God is the primordial expression of Emptiness, but not the only expression. Hills and trees, rivers and stars, are also expressions, And so are people and the decisions they make. Acts of love are expressions of Creativity, but so are acts of hatred. Creativity, like Emptiness, does not have preferences.

Kyoto thinkers will further emphasize that awakening to this ground is not “enjoyed” or “had” by a separate experiencer. It is, in its own way, the self-awakening of Emptiness. Process thinkers influenced by Whitehead can likewise appreciate this idea. In Whitehead’s philosophy the subject of a given moment of experience is not different from the act of experiencing itself. The agent of a given moment is not different from the deciding. There is no separate self standing above or outside experience as its owner or possessor. There is only the experience or, a Nishida would say, the pure experience. This pure experience is not different from ordinary experience. It is the eating in eating, the drinking in drinking, the laughing in laughing, the crying in crying. Every experience is the self-awakening of Emptiness.

Still, of course, there is within each of us, add process thinkers, some kind of inner lure, inner calling, toward wisdom and compassion, toward insight and love. It is present as a potential to be realized and also a potential that beckons. It is within each person, given in pure experience. For theistic process thinkers, this beckoning is where God is in experience. In the Kyoto School, it is not thus named, but it has resonance with that within each person that feels a need, a desire, to make and live from a vow: that is, a vow to save all sentient beings. This Bodhisattva vow is also part of pure experience.

One value of the Kyoto School is that it orients us toward the groundless ground of all that is. Another value is that it invites us to live in non-ego based ways for the sake of other people, other animals, and the earth. Thus it leans toward the first three hopes of the process movement: whole persons, whole communities, and a whole planet. And it is itself a viable option for the fourth hope: holistic thinking that is honest, spiritually deep, probing, and enlightened.

Thus, on this page, I offer essays by Nicole Bea Pastoukoff, about one of the seminal thinkers of the Kyoto School, Kitaro Nishida. Originally published in her website The Kyoto School of Philosophy, she has given me permission to repost her three introductory essays in Open Horizons. For that, and much else, I am grateful.

'

Jay McDaniel

New to it? Two excellent websites for learning about it are: The Kyoto School of Philosophy and The Way of Emptiness. Both are created and curated by an independent scholar and Zen practitioner, Nicole Bea Pastoukoff. Her websites have essays and articles on three figures in the Kyoto school: Nishida Kitaro, Nishitani Keiji, and Ueda Shizuteru plus much more: essays on Theravada, Indian Mahayana, East Asian Buddhism, Japanese Buddhism, and Contemporary Buddhist Philosophy. The Way of Emptiness is especially remarkable in its scope and depth. With her permission, Open Horizons will be publishing more of her material. This page, however, offers three essays from The Kyoto School website.

My thesis is simple. It is that the Kyoto School offers a different kind of process philosophy. To be sure, it builds upon process themes such as inter-becoming, the primacy of moments of experience, the mutual immanence of all things, and the idea that the process of experiencing the world, as undertaken and undergone in human life, has no separate experiencer. But there is one more theme that it also builds upon, namely that the ultimate reality is Emptiness not God. Or, as Whitehead might put it, Creativity not God. An important feature of process philosophy as influenced by Alfred North Whitehead is that it distinguishes the ultimate reality of Creativity from the God of love, affirming both.

Of course everything depends on what is meant by process philosophy. For a brief overview of the process perspective, see The Twenty Key Ideas of Process Thought on home page of Open Horizons. Some ideas will sound very Buddhist: we live in a universe of mutual becoming in which all things are present in all of things; there is something like inwardness or subjectivity in each and every actuality; reality itself is pure becoming or process. For process thinkers, these ideas are important, not simply because they are true to the nature of things, but because, if taken to heart, they can help create a better world. The four aims of the process movement are to help people become more whole as individuals; to foster compassionate and just communities that are good for people, other animals, and the earth; to protect and care for the planet as a whole; and to encourage holistic ways of thinking that recognize the interconnectedness of all things, the intrinsic value of life, and the processive nature of reality.

Many process philosophers and theologians from the West and influenced by Abrahamic traditions add that holistic thinking includes the recognition of a divine source or companion, God, who embraces the whole and lures creation toward beauty, diversity, and goodness. Often they naturally and understandably assume that a process-relational point view includes a belief in God – not an authoritarian God of coercion, but a loving God of persuasion. A God who is not separate from the universe but who is the very mind of the universe. Some call it pan-en-theism: everything in God even as God is more than everything.

However, there are some for whom this belief in God, even the process God, is not religiously compelling. They are drawn toward alternative process perspective which emphasize the ultimacy of interconnectedness or the ultimacy of an energy, consciousness, or creativity which, as they see things, is truly the ground of all things.

This is where the Kyoto School of Buddhist philosophy can make more sense. It does indeed speak of a ground to all things, but also emphasizes that it is a groundless ground. It is not a creator or even a generative source; it is not a substance or a thing; it is not a creator or agent. Nishida speaks of it as the field of force by virtue of which all things as they are in themselves gather themselves into one: the field of the possibility of the world (RN 150-51), It is best understood, not when believed in but rather when directly experienced. And yet even this experience is easily misrepresented. It is not a mystical awakening to something deeper or higher than the world around us, it is an awakening to a kind of emptiness that is coincident with the world, not separated as a transcendent object.

For process thinkers, this Emptiness akin to the Creativity of which Whitehead speaks. This Creativity is not God. It is a groundless ground of which even God is an expression along with everything else in the universe. God is the primordial expression of Emptiness, but not the only expression. Hills and trees, rivers and stars, are also expressions, And so are people and the decisions they make. Acts of love are expressions of Creativity, but so are acts of hatred. Creativity, like Emptiness, does not have preferences.

Kyoto thinkers will further emphasize that awakening to this ground is not “enjoyed” or “had” by a separate experiencer. It is, in its own way, the self-awakening of Emptiness. Process thinkers influenced by Whitehead can likewise appreciate this idea. In Whitehead’s philosophy the subject of a given moment of experience is not different from the act of experiencing itself. The agent of a given moment is not different from the deciding. There is no separate self standing above or outside experience as its owner or possessor. There is only the experience or, a Nishida would say, the pure experience. This pure experience is not different from ordinary experience. It is the eating in eating, the drinking in drinking, the laughing in laughing, the crying in crying. Every experience is the self-awakening of Emptiness.

Still, of course, there is within each of us, add process thinkers, some kind of inner lure, inner calling, toward wisdom and compassion, toward insight and love. It is present as a potential to be realized and also a potential that beckons. It is within each person, given in pure experience. For theistic process thinkers, this beckoning is where God is in experience. In the Kyoto School, it is not thus named, but it has resonance with that within each person that feels a need, a desire, to make and live from a vow: that is, a vow to save all sentient beings. This Bodhisattva vow is also part of pure experience.

One value of the Kyoto School is that it orients us toward the groundless ground of all that is. Another value is that it invites us to live in non-ego based ways for the sake of other people, other animals, and the earth. Thus it leans toward the first three hopes of the process movement: whole persons, whole communities, and a whole planet. And it is itself a viable option for the fourth hope: holistic thinking that is honest, spiritually deep, probing, and enlightened.

Thus, on this page, I offer essays by Nicole Bea Pastoukoff, about one of the seminal thinkers of the Kyoto School, Kitaro Nishida. Originally published in her website The Kyoto School of Philosophy, she has given me permission to repost her three introductory essays in Open Horizons. For that, and much else, I am grateful.

'

Jay McDaniel

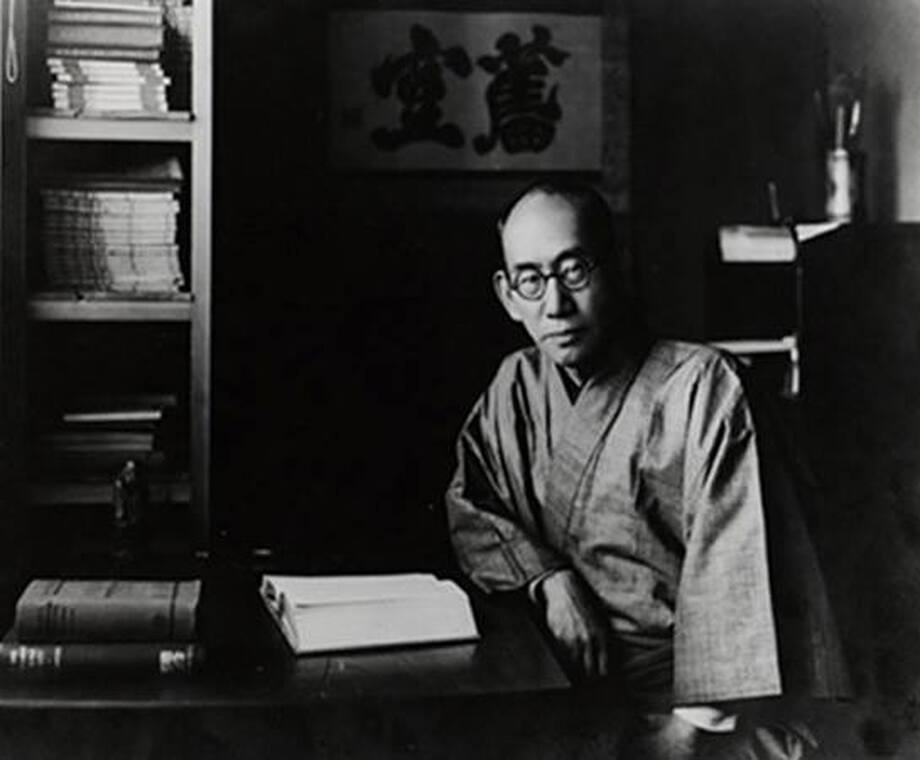

Introducing Nishida

Nicole Bea Pastoukoff

Soon after Nishida Kitaro’s appointment at Kyoto Imperial University in 1913, a regular circle of students began to meet with the new professor, often at his house, for passionate discussions. Out of this circle, a number of gifted and like-minded philosophers emerged to form what came to be known as the Kyoto School of Philosophy. Though their works, now covering three generations, are diverse, they have followed in Nishida’s footsteps in so far as they have used the language of Western philosophy to reformulate the insights at the core of the Eastern apprehension of reality: in other words, they have all given a central place to nothingness.

It can safely be said that outside the academic world, very few are those who have even heard of the Kyoto School. It is my belief that this is a great loss, as history provided these philosophers with the unique privilege of combining within their cultural make-up the Eastern understanding of reality as actual experience in the here and now – what came to be referred as “the standpoint of emptiness” – and the ability to use the rational and objective language of Western philosophy, which could be said to be that of the standpoint of ego-centredness and that of being. Nishida’s point was not, however, a simple comparison of the Eastern and Western views of reality. His thought is, rather, an in-depth inquiry showing how the two standpoints can be integrated within a broader understanding of reality.

There is no denying that we have reached a turning point in history: the ego-centred games on which Western democracies are based cannot provide lifestyles respectful of the planet. Most of those who are trying to transcend ego-centredness are in fact regressing to a sort of pre-egoic state where one actually abdicates responsibility in favour of an authoritarian figure. This is a dangerous confusion of pre-egoic with trans-egoic. As cognitive science also asserts, the world we see is not outside us. It is “created” by the processes of our consciousness. Therefore, to overcome the problems we take to be in the “outside” world, we need to alter our view of the world, through an inner transformation whereby, as we empty the self and allow empathy to arise, we will spontaneously act ethically while accessing genuine subjectivity, that which can be truly called a trans-egoic activity.

For these reasons, and others, I believe that there is a lot Nishida and the Kyoto School can help us to understand, and this is the reason behind this website, which though imperfect, is a sincere attempt at offering an introduction in the hope that this will encourage further reading.

Three introductory texts are followed by a more detailed presentation of Nishida’s thought and short presentations on two other members of the School, Nishitani and Ueda.

It can safely be said that outside the academic world, very few are those who have even heard of the Kyoto School. It is my belief that this is a great loss, as history provided these philosophers with the unique privilege of combining within their cultural make-up the Eastern understanding of reality as actual experience in the here and now – what came to be referred as “the standpoint of emptiness” – and the ability to use the rational and objective language of Western philosophy, which could be said to be that of the standpoint of ego-centredness and that of being. Nishida’s point was not, however, a simple comparison of the Eastern and Western views of reality. His thought is, rather, an in-depth inquiry showing how the two standpoints can be integrated within a broader understanding of reality.

There is no denying that we have reached a turning point in history: the ego-centred games on which Western democracies are based cannot provide lifestyles respectful of the planet. Most of those who are trying to transcend ego-centredness are in fact regressing to a sort of pre-egoic state where one actually abdicates responsibility in favour of an authoritarian figure. This is a dangerous confusion of pre-egoic with trans-egoic. As cognitive science also asserts, the world we see is not outside us. It is “created” by the processes of our consciousness. Therefore, to overcome the problems we take to be in the “outside” world, we need to alter our view of the world, through an inner transformation whereby, as we empty the self and allow empathy to arise, we will spontaneously act ethically while accessing genuine subjectivity, that which can be truly called a trans-egoic activity.

For these reasons, and others, I believe that there is a lot Nishida and the Kyoto School can help us to understand, and this is the reason behind this website, which though imperfect, is a sincere attempt at offering an introduction in the hope that this will encourage further reading.

Three introductory texts are followed by a more detailed presentation of Nishida’s thought and short presentations on two other members of the School, Nishitani and Ueda.

A Different Kind of Philosophy

Nicole Bea Pastoukoff

“The one is self-contradictorily composed of the many, and the many are self-contradictorily one. The world can be viewed in two directions – the double aperture – and its unity is not the unity of oneness, as the mystic would likely express it, but the unity of self-contradiction. It is both one and many; changing and unchanging; past and future in the present. Nishida’s dialectic has as its aim the preservation of the contradictory terms, yet as a unity … This is the logic of soku, or sokuhi – the absolute identification of the is, and the is not. In symbolic representation: A is A; A is not-A; therefore A is A. I see the mountains. I see that there are no mountains. Therefore I see the mountains again, but as transformed. And the transformation is that the mountains both are and are not mountains. That is their reality.” (Robert E Carter, The Nothingness Beyond God -An Introduction to the Philosophy of Nishida Kitaro, 58)

The Kyoto School of Philosophy

Founded in 1897, Kyoto Imperial University sought to distinguish itself from the older Tokyo Imperial University by “designing a unique curriculum and adopting an unconventional method of hiring professors … they chose to hire men of talents far beyond the confines of academic walls … a policy of “identifying talents in the wild.” (Michiko Yusa, Zen & Philosophy – An Intellectual Biography of Nishida, Kitaro, 117). Nishida joined its College of Humanities in 1910, and in 1913-1914 was appointed full professor first in the study of religion, then in the very first chair for the history of philosophy. Nishida had a strong personal presence as a teacher, thinking aloud as he paced the floor back and forth, and exerted a cult-like fascination on his students. 1911 saw the publication of his first work, An Inquiry into the Good, which, Yusa says, “had the effect of a small stone thrown into a calm pond.” (Yusa, Ibid, 128). A reprint in 1921 turned it into a best seller. Though not easy reading, a large audience of Japanese readers resonated with Nishida’s inquiry. By then, the department of philosophy at Kyoto University had displaced that of Tokyo as the best in Japan, and a regular circle of students had begun to meet with Professor Nishida, often at his own house, for passionate discussions. Out of this circle, a number of gifted and like-minded philosophers emerged to form what came to be known as the Kyoto School. Though their works, now covering three generations, are diverse, they can be said to have followed in Nishida’s footsteps as they all gave a central place to nothingness.

Following the treaty the US had imposed on Japan, which compelled it to open up its borders to trade, a rapid westernization of the country took place under the leadership of the restored emperor during what has been called the Meiji Restoration. Born in 1870, that is, two years after the restoration, the young Nishida received an education still based on the traditional study of Chinese Classics. His first encounter with the West came through the study of mathematics. He eventually chose to study Western philosophy at Tokyo Imperial University. Before embarking on his own philosophical inquiry, however, he engaged in a decade-long Zen practice. In other words, Nishida was pretty much a man of the East, and what this meant is that he shared the Eastern apprehension of reality as an embodied experience of change as life arises out of nothingness to give shape to phenomena. He was also convinced that this view of reality, though primarily experiential, could be articulated in the language of Western philosophy, though Western philosophy had been developed on the assumption that reality is “being,” with nothingness defined as an absence of being. Nishida sought to ensure that what has been called “Asian nothingness” remained accessible to later generations of Japanese, in spite of the westernization process they would have gone through. To be sure, the Buddha himself had tried to reformulate the Indian subcontinent’s native spirituality in the language and mode of thinking of Brahmanism, and it had not been easy for him to express his core teaching of anatman “no-own being” in a philosophical language based on being.

The trouble with Aristotle

In many ways, Nishida was faced with the exact same problem. The philosophy he had learned as a student was also based on the Indo-European ontological mode of thinking. The difference, however, was that, over the centuries, and especially after going through the Age of Enlightenment in the 18th century, the ontological philosophical mode of thinking had reinvented itself several times. Idealism, which had been the dominant school, deriving its name from Plato’s “Ideas,” equated “being” with abstract “Forms” transcending reality as experienced by the senses. With Aristotle, the being of a thing was defined through the superimposition of a name which was a universal, and could not, therefore, truly express the uniqueness of the particular thing given in experience. Idealism had later been redefined by Kant as the notion that we can never see reality as it is, we can only see it as shaped by the structures of our minds. And Hegel had already gone beyond Aristotle’s emphasis on the principle of non-contradiction when he described reality as unfolding through a process of contradiction with a thesis, an anti-thesis, and a synthesis, which resolved the contradiction and recovered a unified view. Even more significantly for Nishida, a group of philosophers calling themselves empiricists, had started to rebel against idealism itself – the notion that the really real is a mind-based abstraction – and was calling for a return to experience. Nishida read William James’s The Varieties of Religious Experience in 1904, and Henri Bergson’s works soon after. Reality as an experienced, concrete, embodied apprehension of the world by the heart-mind, was precisely the way the East had always understood reality.

A lot has been written about this particular way the East approaches reality from a standpoint of xin (Japanese kokoro), the heartmind, where the world is felt, intuited, originally even divined, more than it is analysed, a procedure which involves a cutting up of the world into parts which are later rearranged into a meaningful system. It has been suggested that the use of ideogrammes which retain the shape of the things used as images, in contrast to the European use of alphabets based on sounds – phonics – helped preserve a concrete grasp of reality in China. Another reason behind the difference between the Eastern and Western modes of thinking may be the East’s comparatively gentler inclusion of native spiritualities, using shamanic ecstasy, divination, and intuition, in other words, lunar consciousness, seeking “in-sights” rather than drawing sharp boundaries, in contrast with the much more aggressive prohibition of all things pagan in the West, and its strong assertion of solar consciousness, insisting on clarity and meaning. Nishida shared this Eastern experiential apprehension of reality, and saw it as akin to the return to “direct, or pure, experience” James and Bergson were calling for. He then equated the Zen state of no-mind as experience of facts “just as they are.” In his own words: “To experience means to know facts just as they are, to know in accordance with facts by completely relinquishing one’s own fabrications … by pure I am referring to the state of experience just as it is without the least addition of deliberative discrimination.” (Nishida, An Inquiry into the Good, 3). That, at the same time, amounted to doing philosophy from the standpoint of nothingness so, definitely, a different kind of philosophy, since philosophy in its Greek and European forms, approaches reality from the standpoint of being.

The standpoint of nothingness

But doesn’t “no-mind” mean “no-thought”? Is it possible to do philosophy from the standpoint of nothingness? Well, one of the first assertions Nishida makes is that “pure experience includes thinking.” (Nishida, Ibid, 17). Unless we are newborns with an undifferentiated consciousness, we do see “things.” Things appear to us when given a name, so whatever we see is by definition the product of the mental activity of naming. What Nishida called “fabrications” and “deliberative discrimination” referred to mental elaborations rooted in attachment to ego and the confused ruminations the ego is thrown into when trying to defend itself! What “nothingness” really means is a non-attachment to form which allows us to see things as they are, without ego-based distortion. We are thus able to let the flow of life take place, and the “natural” dynamism of the formless manifest as forms, without trying to interfere, grasp, or reject. We have to be empty in that sense in the present moment, and resonate with reality as it unfolds. By contrast, philosophy as done in the West reifies reality into an order whose operating system, as it were, is causality. In the Principle of Reason, Heidegger elucidates Leibniz’s “Nihil est sine ratione,” – “nothing is without a reason,” as “nothing is without a cause” adding, of course it is, since what “is” has been defined from the start as what has a cause! The tautology has substantialized what being is. In a nutshell, if you take Einstein’s assertion that matter and energy are one and the same reality seen from two different perspectives, the West has chosen the perspective of matter – a solid substantial world which one seeks to control – and the (ancient) East has chosen the perspective of energy – a flowing dynamic reality which one allows oneself to flow with, interact with, adjust to, so that one lives with it as if borne by it.

The double aperture – things are and are not, they are “lined with nothingness”

Nishida’s intuition was that the standpoint of nothingness was not merely another perspective on reality. It was a deeper standpoint which embraced the standpoint of being in the way the cosmic order embraces human existence and activity. To show this convincingly, he used the language of philosophy, and presented a fuller picture of reality by showing that what he came to call the “logic of the place of nothingness” embraced “object logic,” that is, Aristotle’s logic, based on the laws of reason. More specifically, he showed that what he calls the “logic of self-contradictory identity” is valid at a deeper level of reality than Aristotle’s law of non-contradiction. So his logic was not, as such, a challenge to Aristotle’s logic, which remained correct at the level of ordinary practical life. Again, the relation between the two is reminiscent of that between quantum physics, whose laws hold at the level of the infinitely small, and traditional Newtonian physics, which we still use in our everyday lives.

Aristotle’s law of non-contradiction asserts that A is A, and cannot be at the same time not-A. Obvious enough, isn’t it? That is what Nishida calls “object logic.” This is the sort of logic which one finds operating at the level of ordinary consciousness, where things are seen as objects seemingly displayed on a screen in front of us. At a deeper level, Nishida argues, reality arises according to the “logic of the place of nothingness,” which he characterises as “self-contradictory identity,” – in Japanese zettai mujunteki jikodoitsu, which means literally “the self-identity of absolute contradictories.”(Carter, The Nothingness Beyond God, 61). “Unity of opposites” is less of a mouthful and can be used as shorthand for what is a logical reformulation of the Buddhist doctrine of co-dependent origination. All things arise co-dependently as pairs of opposites: I get to know what “long” is at the same time as I get to know what “short” is, that is, I know A as not A, but at the same time A owes its existence to its opposite “not A.”

In his presentation of Nishida’s thought, Robert Carter uses the well-known Qingyuan Weixin Chinese epigram to explain self-contradictory identity:

Thirty years ago, before I began the study of Zen, I said, ‘Mountains are mountains, waters are waters.’ After I got an insight into the truth of Zen through the instruction of a good master, I said, ‘Mountains are not mountains, waters are not waters.’ But now, having attained the abode of final rest [that is, Awakening], I say, “Mountains are really mountains, waters are really waters.’

In the first line, ordinary consciousness posits mountains and waters as objects whose existence I do not normally question. But after learning that things only appear when given a name, I come to see them as just shapes drawn by the mind in an otherwise undifferentiated oneness. When you get to the 3rd line, which is the view of enlightened consciousness, it is clear that mountains and waters, though really empty of being, are the phenomenal forms I live my life with – I do not live my life in undifferentiated oneness. Though they are experientially real, since mountains and waters are still “empty of own being,” my life with these empty forms is indeed a life lived in emptiness.

Robert E Carter explains self-contradictory identity as follows: “The one is self-contradictorily composed of the many, and the many are self-contradictorily one. The world can be viewed in two directions – the double aperture – and its unity is not the unity of oneness, as the mystic would likely express it, but the unity of self-contradiction. It is both one and many; changing and unchanging; past and future in the present. Nishida’s dialectic has as its aim the preservation of the contradictory terms, yet as a unity … This is the logic of soku, or sokuhi – the absolute identification of the is, and the is not. In symbolic representation: A is A; A is not-A; therefore A is A. I see the mountains. I see that there are no mountains. Therefore I see the mountains again, but as transformed. And the transformation is that the mountains both are and are not mountains. That is their reality.” (Ibid , 58).

Having said that reality as self-contradictory is not a direct challenge to Aristotle’s law of non-contradiction, I have to add now, that since Nishida asserts that the former is more fundamental than the latter – since it encompasses and includes the latter -, he is still advocating it as truer, because more complete, than the latter. Aristotle’s non-contradiction posits that the mountains are. Nishida’s unity of opposites show that the mountains are and are not mountains. They are, but they are also “lined with nothingness.”

The logic of the place of nothingness as a religious worldview

Nishida’s last work is called “The Logic of the Place of Nothingness and the Religious Worldview.” Some readers may have felt uneasy about Nishida’s assimilation of the empiricists’ quest for direct experience – a quasi-scientific investigation of reality – with the Zen state of no-mind, which is also that of Buddhist enlightenment, that is, a spiritual state of realisation said to be only achieved by a few. Nishida’s last work confirms that the view of reality as self-contradictory is indeed the religious worldview. It is, more precisely, the religious worldview as understood in the East, where religion is not a matter of belief in a set of scriptures, but a practice leading to an inner transformation allowing us to apprehend reality in an enlightened way. This does not, however, imply that only fully enlightened individuals can understand it. Dedicating oneself to a practice leading to enlightenment allows what is originally a mere intellectual grasp of the logic of self-contradictory identity to grow into a lived view of reality through the “double aperture,” both real and unreal, or “real in its unreality.”

Enlightenment is rarely a big flash of realisation, but much more often a long process of maturation. Basically, to be religious is to dwell in the standpoint of nothingness, in the present moment, again and again emptying oneself of one’s (ego-)self, until one actually “forgets” one’s self – which triggers empathetic coalescence with all beings: not being one’s self, one can be all beings and all things.

And from that standpoint of nothingness, free of bias, one can see “things as they are” and one can do “what needs to be done.” Thus, all individuals are called upon to co-express the formless into the world of forms, from the standpoint of no-self. No-self, correctly understood, means that the self is not a “thing,” it can never be seen as an object – whether a soul or an organ -, at the most, it could be called a “function”. Nishida describes it as the activity of consciousness, as it allows the self-determination of the formless into forms. So, the true self is the activity giving form to the formless.

In Nishida’s words: “the self is to be understood as existing in that dynamic dimension wherein each existential act of consciousness, as a self-expressive determination of the world, simultaneously reflects the world’s self-expression within itself and forms itself through its own self-expression.” (Nishida, "The Logic of the Place of Nothingness and the Religious Worldview" in "Last Writings" p. 64(

Now, is religion as understood in the West all that different? When described as a belief in a higher authority – whose utterances are recorded in sacred books – it appears to be little more than a medium to ensure social cohesion through a submission of individual wills to the higher authority of a revealed truth. It is in no way a practice allowing individuals to achieve the standpoint of nothingness from which they can have direct access to the truth – i.e., see things as they are. Nishida, however, sees a common ground between all religions. A large part of Nishida’s last work is a reflection on Christianity, where he regularly uses the word God, usually as another name for nothingness. For him, it is easy to see that in Judaeo-Christian religions, surrender to a higher being is the means used to allow individuals to realise the state of no-self – the small ego-self is replaced by the higher being, whose will one submits to. This approach is called that of “other power,” and is also found in the Buddhist Pure Land School, which most Japanese belong to. Zen is said to belong to the “own power” approach, meaning that one realises – knows and appropriates – the fact that there is no such thing as an (individual) self. But, Nishida adds, Zen no-self is not really “own power” since “own power” presupposes a self as the source of that power! Only when it negates itself does the self can be said to have power, and at that point it is not a self. It is a no-self which, as we saw, is really an activity seemingly surging from below us. In fact, in Japan, the two approaches are widely regarded as the same path seen from two different angles.

True emptiness, wondrous being

As he reformulated the Eastern standpoint of nothingness in philosophical terms, Nishida also hoped it would make it possible for Japanese to engage more fully with the outside world. From its inception in India, Buddhism has been seen as a spiritual journey requiring that one leaves home and society, and enter a monastery. Zen was no different. This is why ordinary Japanese belong to the Pure Land School, but their engagement is not as deep. On the other hand, Nishida felt that most Japanese lacked the sort of critical spirit he saw in the West as the foundation of democracy. Remember that Nishida lived at a time when attempts at setting up a democratic system in Japan eventually failed under the pressures of nationalists who took the country to war. Nishida’s last work was written in the spring of 1945, as he was literally surrounded by the bombs dropped by US fighter planes, and Japan was rushing to a certain defeat. How would the reconstruction be carried out after that imminent defeat? Ordinary people had to be encouraged to think and contribute to the shaping of the worldview, but they were to do it from the standpoint of nothingness, not that of being, as proposed by the West. Not only was the standpoint of nothingness the standpoint they were taught as Japanese – so, the core of their own culture – but, as Nishida argues above, it is a deeper standpoint than that of being, which is that of the ordinary consciousness used in practical life. And, because it was deeper and truer, it would help avoid the excesses committed by the West where it was believed that success, or happiness, can only come from enhancing one’s being – through consumption, wealth, status, etc. – so that life at all levels becomes a game of one-upmanship, with ruinous consequences for the environment as there can be no end to the wish to be more, or to control more of the world. For a democracy to produce a healthy individual, a healthy society and a healthy environment, one must call upon the ancient practice of self-control of one’s desires and fears, and see that a finite world cannot satisfy infinite desires, and there is a need to adjust one’s demands to what the world can sustainably provide. In fact, the mere practice of self-emptying and dwelling in nothingness, associated with empathetic coalescence with all beings, will generate for a large part the sort of satisfaction ego-centred people are looking for in shopping malls, clubs, cruises and holidays under the sun! Contentment is not the satisfaction of one’s desires, it is having no desires.

The path to true self-realisation is nothingness: “True emptiness, wondrous being,” as the famous line has it. Or, as Thomas Merton said in Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander: “From moment to moment I remember with astonishment that I am at the same time empty and full, and satisfied because I am empty. I lack nothing.”

True Emptiness, Wondrous Being

Nicole Bea Pastoukoff

“A monk once asked Joshu, “What is the meaning of the Patriarch’s coming from the West?” Joshu answered: “The oak tree in the front garden.” (Zenkei Shibayama, The Gateless Barrier Zen – Comments on the Mumonkan, 259-260)

“That it is” and “what it is”, the actual and the rational

This is one of these irritating koans which cause most Westerners to think: Enough of this trying to be smart … what about speaking clearly in terms that everyone can understand! The commentator in the Gateless Barrier explains that you need a bit a background to even begin to understand. The Patriarch referred to here is Bodhidharma, who came to China from South India in the 5th or 6th century, and is said to have laid the foundations for Zen, thereby becoming the First Patriarch of the Chinese Zen lineage. To be sure, many scholars believe this is a legend, but this does not matter here. As Zen developed in China, the phrase “What is the meaning of the Patriarch’s coming from the West” has been used to mean “What is the Truth of Zen?” So what is the Truth of Zen? “The oak tree in the front garden,” said Joshu. What the oak in the front garden stands for is the actual concrete existence of reality, “that it is”, rather than the “what it is” we get from language, which only represents reality as interpreted by the mind. The teacher could have said “the bird singing on the branch” or “the snow falling on the roof.” Any occurrence taking place right now, without any meaning, or justification, or goal, would do. Heidegger would have said: “it worlds” – “es weltet” –. But even this is already philosophical. “The oak tree in the front garden” is simple and punchy. Yet it is so difficult to really take in.

There were no koans in Indian Buddhism. The Chinese mind invented koans to point to concretely experienced reality when and where it had come to be hidden by words or representations. The koan starts with a question put at the level of cognition, “what is the meaning of …?” The reply is designed to stop the inquirer in their tracks, as it is formulated in a different type of language, that of observation, rather than that of discursive thought. There is a temptation to take the answer as poetry, and look for a symbolic meaning. That would be looking for an epistemological “what.” The absence of the verb “to be” should trigger a flash of intuition causing the monk to break through the cognitive mode, and see that the real is the actual, concretely experienced present, things as they are, with no meaning, or purpose. The oak tree in the front garden.

Magritte used art to produce a similar effect in his painting “Ceci n’est pas une pipe.” This is not a pipe, it is the representation of a pipe. Note that Magritte still uses the verb “to be,” a loaded word in Western philosophy, while Joshu only juxtaposes the oak tree and the front garden. Remember when you told your toddler, pointing to images on a book, “this is a cow,” or “this is a horse” … Well, you were lying, weren’t you? Worry not, though. Learning the names of things is one step on the way. No one can get from what has been called unenlightened non-dualism – the early undifferentiated consciousness of the baby – in one single leap to enlightened non-dualism – the awakened mind. As a child and young adult, one does need to learn dualism, and at first it will be non-enlightened dualism – basically everything one learns at school – and later it may become enlightened dualism – if one reads philosophy or follows a spiritual practice. Though insights into non-dualism may take place at any time, it takes practice to actually accept non-dualism as the standpoint of everyday life, especially since, as Nishida said, “Pure experience includes thinking.” (Nishida Kitaro, An Inquiry into the Good, 17) That is, non-dualism includes dualism.

Nishida was a follower of Rinzai Zen, a school known for its systematic use of koans to lead its practitioners to awakening. Michiko Yusa tells us that Nishida worked on the koan “Joshu and the Dog” from his very first sesshin. It goes like this: “Someone asked Master Joshu whether the dog has a Buddha nature. To this, Joshu replied, “Mu” (it has not). On another occasion, to the same question Joshu answered, “U” (it has).” Yusa explains: “The discursive question of whether the dog has a Buddha nature presupposes a dichotomy between subject and object; thus, it does not touch the vitally living reality, whether it is a dog’s or a person’s. Actual vibrant reality is before “it has” and “it has not.” (Michiko Yusa, Zen and Philosophy – An Intellectual Biography of Nishida Kitaro, 69)

“A rational foundation for Zen.”

Nishida was told that he had “passed” his koan, but he felt disappointed. He obviously expected “awakening” to be something a bit more dramatic! For some, realising that one has confused the representation of reality with its actuality is quite a revelation. But for Nishida, it seems that the “problem” was elsewhere. As he saw Japan swamped by a tidal wave of Western concepts, abstract theories and ideologies, he was worried that the sort of intuitive breakthrough from the representation to actuality used in koans would no longer “work.” He is said to have “stated in his lectures that his aim was to establish ‘a rational foundation for Zen.’” (Robert E Carter, The Kyoto School, 14). He had this early conviction that objective thinking, no more than any other activity, was not the opposite of concrete experience, but was included in it. All humans use representations to get on with practical living, the Chinese and the Japanese, just as much as the Westerners … Anthropologists who have studied the cultures of foraging populations who cannot write, and know nothing of reason or objective thought, still have names to represent the things which matter to them. Using words is using abstract concepts, it is already living at a remove from the concrete. Names bring about “things,” arising from the indifferentiated “sensory muchness” of pure experience, as forms out of the formless nothingness. And Nishida wanted “to capture [the] standpoint from which everything emerges and to which it returns” (Nishida, “My Philosophical Path,” quoted by Yusa, Zen & Philosophy, 301) and articulate it in the philosophical terminology of the West.

“Pure experience” and “no-mind” – the true reality of the universe beyond objective logic

Having first looked for inspiration in the works of William James and Henri Bergson, who both had criticized discursive thought, and attempted a return to pure or direct experience, using intuition to grasp reality, Nishida had to leave them behind because neither had had access to the Zen practice of no-mind, whereby the self dis-identifies from thoughts, and realises itself as nothingness. As a result, James and Bergson could not go beyond the psychological approach which posited an individual endowed with consciousness looking at a world outside. Their views remained shaped by “object logic” – the view from outside.

Nishida stated early on that he wanted to inquire into “the true reality of the universe,” (Yusa, Ibid, 23) but he wanted to carry out “a philosophical inquiry in a wholly different manner, that is, from the vantage point of the “real self.” (Yusa, Ibid, 66) By real self, he meant the no-self of Zen. Unlike a Zen master in charge of novices in a monastic community, Nishida was not trying to bring monks to awakening. What he had set up himself to do was to inquire into the nature of the world as experienced from the standpoint of awakening. He used the language of Western philosophy rather than that of early Indian Buddhist philosophers, because it was necessary for him to express his thought in the language which the Japanese were increasingly using in their everyday lives as they modernized the country.

Using the conceptual abstract language of Western philosophy to describe the concretely experienced reality which awakening is meant to usher you into, is of course an apparently absurd thing to undertake. Buddhism has had a long history of rejecting all things intellectual, and Zen has been especially rigorous in its anti-intellectual stance. Zen relies on a blend of working on koans, meant to give the practitionners flashes of insight into concrete reality, and week-long silent retreats including hours of sitting every day, meant to allow that insight to “sink in” and become as it were embedded in your way of life. What allowed Nishida to feel justified in attempting his philosophical inquiry is the insight that “pure experience includes thinking.” What had to be done is to describe the process through which thoughts arose from concrete experience, and to show that the problem is not with concepts per se. We could not live without concepts. What we must do, though, is look into the way they arise, and make sure we use them in the right way. The mainstream worldview holding sway wherever you happen to be in the world is the product of minds which operated from an ego-centred standpoint and whose interpretation of reality is distorted by attachments – greed, fear and ignorance. So the first move is to show that only the ego-less no-mind can see things as they are. The move from ego-centredness to no-mind is what, in his last writings, Nishida calls “a turning of the self,” and it is this, very precisely this, that Nishida takes to be the embrace of a religious worldview. Becoming religious, therefore, is not adopting a particular “sacred text” as a revelation of the truth received by some prophet of the past, purported to be a record of the way things are, once and for all. On the contrary, becoming religious is to reject all texts, “kill the Buddha,” and embark on the task of emptying one’s self so that one is a transparent vehicle for an undistorted self-expression of the world. In addition, becoming religious is to gain the ability to see the world through what Robert Carter calls the “double-aperture,” seeing at once the conceptual interpretation, and the fact that this interpretation is only a temporary take on things, at a particular moment, in a particular context: in other words, it is conditioned, and one should be ready to let it go if it proves to become incorrect due to changes taking place. This is also what Carter calls “seeing things lined with nothingness.”

“That it is” and “what it is”, the actual and the rational

This is one of these irritating koans which cause most Westerners to think: Enough of this trying to be smart … what about speaking clearly in terms that everyone can understand! The commentator in the Gateless Barrier explains that you need a bit a background to even begin to understand. The Patriarch referred to here is Bodhidharma, who came to China from South India in the 5th or 6th century, and is said to have laid the foundations for Zen, thereby becoming the First Patriarch of the Chinese Zen lineage. To be sure, many scholars believe this is a legend, but this does not matter here. As Zen developed in China, the phrase “What is the meaning of the Patriarch’s coming from the West” has been used to mean “What is the Truth of Zen?” So what is the Truth of Zen? “The oak tree in the front garden,” said Joshu. What the oak in the front garden stands for is the actual concrete existence of reality, “that it is”, rather than the “what it is” we get from language, which only represents reality as interpreted by the mind. The teacher could have said “the bird singing on the branch” or “the snow falling on the roof.” Any occurrence taking place right now, without any meaning, or justification, or goal, would do. Heidegger would have said: “it worlds” – “es weltet” –. But even this is already philosophical. “The oak tree in the front garden” is simple and punchy. Yet it is so difficult to really take in.

There were no koans in Indian Buddhism. The Chinese mind invented koans to point to concretely experienced reality when and where it had come to be hidden by words or representations. The koan starts with a question put at the level of cognition, “what is the meaning of …?” The reply is designed to stop the inquirer in their tracks, as it is formulated in a different type of language, that of observation, rather than that of discursive thought. There is a temptation to take the answer as poetry, and look for a symbolic meaning. That would be looking for an epistemological “what.” The absence of the verb “to be” should trigger a flash of intuition causing the monk to break through the cognitive mode, and see that the real is the actual, concretely experienced present, things as they are, with no meaning, or purpose. The oak tree in the front garden.

Magritte used art to produce a similar effect in his painting “Ceci n’est pas une pipe.” This is not a pipe, it is the representation of a pipe. Note that Magritte still uses the verb “to be,” a loaded word in Western philosophy, while Joshu only juxtaposes the oak tree and the front garden. Remember when you told your toddler, pointing to images on a book, “this is a cow,” or “this is a horse” … Well, you were lying, weren’t you? Worry not, though. Learning the names of things is one step on the way. No one can get from what has been called unenlightened non-dualism – the early undifferentiated consciousness of the baby – in one single leap to enlightened non-dualism – the awakened mind. As a child and young adult, one does need to learn dualism, and at first it will be non-enlightened dualism – basically everything one learns at school – and later it may become enlightened dualism – if one reads philosophy or follows a spiritual practice. Though insights into non-dualism may take place at any time, it takes practice to actually accept non-dualism as the standpoint of everyday life, especially since, as Nishida said, “Pure experience includes thinking.” (Nishida Kitaro, An Inquiry into the Good, 17) That is, non-dualism includes dualism.

Nishida was a follower of Rinzai Zen, a school known for its systematic use of koans to lead its practitioners to awakening. Michiko Yusa tells us that Nishida worked on the koan “Joshu and the Dog” from his very first sesshin. It goes like this: “Someone asked Master Joshu whether the dog has a Buddha nature. To this, Joshu replied, “Mu” (it has not). On another occasion, to the same question Joshu answered, “U” (it has).” Yusa explains: “The discursive question of whether the dog has a Buddha nature presupposes a dichotomy between subject and object; thus, it does not touch the vitally living reality, whether it is a dog’s or a person’s. Actual vibrant reality is before “it has” and “it has not.” (Michiko Yusa, Zen and Philosophy – An Intellectual Biography of Nishida Kitaro, 69)

“A rational foundation for Zen.”

Nishida was told that he had “passed” his koan, but he felt disappointed. He obviously expected “awakening” to be something a bit more dramatic! For some, realising that one has confused the representation of reality with its actuality is quite a revelation. But for Nishida, it seems that the “problem” was elsewhere. As he saw Japan swamped by a tidal wave of Western concepts, abstract theories and ideologies, he was worried that the sort of intuitive breakthrough from the representation to actuality used in koans would no longer “work.” He is said to have “stated in his lectures that his aim was to establish ‘a rational foundation for Zen.’” (Robert E Carter, The Kyoto School, 14). He had this early conviction that objective thinking, no more than any other activity, was not the opposite of concrete experience, but was included in it. All humans use representations to get on with practical living, the Chinese and the Japanese, just as much as the Westerners … Anthropologists who have studied the cultures of foraging populations who cannot write, and know nothing of reason or objective thought, still have names to represent the things which matter to them. Using words is using abstract concepts, it is already living at a remove from the concrete. Names bring about “things,” arising from the indifferentiated “sensory muchness” of pure experience, as forms out of the formless nothingness. And Nishida wanted “to capture [the] standpoint from which everything emerges and to which it returns” (Nishida, “My Philosophical Path,” quoted by Yusa, Zen & Philosophy, 301) and articulate it in the philosophical terminology of the West.

“Pure experience” and “no-mind” – the true reality of the universe beyond objective logic

Having first looked for inspiration in the works of William James and Henri Bergson, who both had criticized discursive thought, and attempted a return to pure or direct experience, using intuition to grasp reality, Nishida had to leave them behind because neither had had access to the Zen practice of no-mind, whereby the self dis-identifies from thoughts, and realises itself as nothingness. As a result, James and Bergson could not go beyond the psychological approach which posited an individual endowed with consciousness looking at a world outside. Their views remained shaped by “object logic” – the view from outside.

Nishida stated early on that he wanted to inquire into “the true reality of the universe,” (Yusa, Ibid, 23) but he wanted to carry out “a philosophical inquiry in a wholly different manner, that is, from the vantage point of the “real self.” (Yusa, Ibid, 66) By real self, he meant the no-self of Zen. Unlike a Zen master in charge of novices in a monastic community, Nishida was not trying to bring monks to awakening. What he had set up himself to do was to inquire into the nature of the world as experienced from the standpoint of awakening. He used the language of Western philosophy rather than that of early Indian Buddhist philosophers, because it was necessary for him to express his thought in the language which the Japanese were increasingly using in their everyday lives as they modernized the country.

Using the conceptual abstract language of Western philosophy to describe the concretely experienced reality which awakening is meant to usher you into, is of course an apparently absurd thing to undertake. Buddhism has had a long history of rejecting all things intellectual, and Zen has been especially rigorous in its anti-intellectual stance. Zen relies on a blend of working on koans, meant to give the practitionners flashes of insight into concrete reality, and week-long silent retreats including hours of sitting every day, meant to allow that insight to “sink in” and become as it were embedded in your way of life. What allowed Nishida to feel justified in attempting his philosophical inquiry is the insight that “pure experience includes thinking.” What had to be done is to describe the process through which thoughts arose from concrete experience, and to show that the problem is not with concepts per se. We could not live without concepts. What we must do, though, is look into the way they arise, and make sure we use them in the right way. The mainstream worldview holding sway wherever you happen to be in the world is the product of minds which operated from an ego-centred standpoint and whose interpretation of reality is distorted by attachments – greed, fear and ignorance. So the first move is to show that only the ego-less no-mind can see things as they are. The move from ego-centredness to no-mind is what, in his last writings, Nishida calls “a turning of the self,” and it is this, very precisely this, that Nishida takes to be the embrace of a religious worldview. Becoming religious, therefore, is not adopting a particular “sacred text” as a revelation of the truth received by some prophet of the past, purported to be a record of the way things are, once and for all. On the contrary, becoming religious is to reject all texts, “kill the Buddha,” and embark on the task of emptying one’s self so that one is a transparent vehicle for an undistorted self-expression of the world. In addition, becoming religious is to gain the ability to see the world through what Robert Carter calls the “double-aperture,” seeing at once the conceptual interpretation, and the fact that this interpretation is only a temporary take on things, at a particular moment, in a particular context: in other words, it is conditioned, and one should be ready to let it go if it proves to become incorrect due to changes taking place. This is also what Carter calls “seeing things lined with nothingness.”

Emptiness is "I"

Nicole Bea Pastoukoff

It is not that “I am empty,” but rather, that “emptiness is I” (Masao Abe, Zen and Western Thought, 13)

To be religious is to live from the standpoint of emptiness

Nishida goes to great lengths to describe the process whereby ultimate reality, i.e., nothingness, what he also calls the “formless world,” is also dynamic, and self-expresses as the world of forms – the phenomenal/historical world – through the conscious self of each individual, which is a field of nothingness (basho), at once “creating” the world in the present moment, and allowing individuals to become true selves and true individuals. More precisely, the conscious individual selves at all times reflect the world and, as it were, re-process it to match their concrete experience, in a two-way movement which turns individuals collectively into co-creators of the world, not out of any autonomous power, but as conduits for the self-expression of ultimate reality.

In other words, whereas in India, Buddhism tended to contrast the impermanence of illusory phenomena, and the deeper reality of emptiness, presenting awakening as a breaking free from the process of rebirth and a release from the world, in China, and even more so in Japan, reality was seen as change, that is, as such, phenomenal: awakening was simply the realisation that one’s life unfolded in a world of phenomena, which are indeed empty, the forms of the formless. Living in a world of phenomena recognised as being forms empty of own being is living from the standpoint of nothingness. In the Far East, that world of phenomena is a world concretely experienced, lived in its actuality here and now, and impermanence is hailed as activity, dynamism and change: it is life itself. This particular view of the Far East has been referred to as “Asian nothingness” (toyoteki mu).” Whereas the Indian Buddhist anatman (no own being) and Nagarjuna’s sunyata (emptiness) are epistemological concepts – referring to the fact that things are only forms, Asian nothingness refers to a lived experience of reality as a way arising naturally out of nothingness. As Campbell aptly said, India says “All is illusion: let it go,” and China “all is in order, let it come.” In India, enlightenment (samadhi) with the eyes closed, in Japan, enlightenment (satori) with the eyes open. The word moksa (release) has been applied to both, but they are not the same. (Joseph Campbell, The Masks of God – Oriental Mythology, 30-31)

As it welcomed change as an inherent order which should be trusted, China had embarked on a rather involved articulation of the processes of change. In particular, it showed how forms arose as pairs of opposites, symbolised as yin and yang. The Yijing provides a detailed guide of the various configurations which stimulate the diviner’s imagination trying to intuit the unfolding of events in real time. The yin-yang formula constituted the logical system used in various fields, from diet to medicine to architecture to art and of course religious practice.

Present on Nishida’s mind when he articulated his doctrine of “reality as the self-identity of absolute opposites”, for short, “self-contradictory identity” was also the Buddha’s doctrine of co-dependent origination, which can be regarded as the Indian form of the yin-yang logic. In co-dependent origination, all concepts are described as arising in interdependence with each other. This includes an arising in pairs of opposites – short and long, right and left, light and dark, life and death, good and evil. One cannot know what short is unless one also knows what long is. Each step in the process of change is as such a death-life process as the old must “die” to make way for the new. More widely, this includes the interconnectedness of phenomena in nature, how species develop relative to each other, how any occurrence anywhere triggers changes near and far, as everything at all times interacts with everything else.

Western philosophy failed to express the uniqueness of the particular, that which is actually experienced

But, rather than explicitly starting from either yin-yang or co-dependent origination, Nishida turned to Aristotle! This was of course to be expected from a philosopher wishing to use the language of Western philosophy. After Plato, Aristotle is regarded as the founder of metaphysics, the view that reality is Being, as logos, meaning that it is shaped by Ideas, ideal forms existing either in a metaphysical supra-sensory world, or as abstracted from what we see and experience, and as it were, embodied in words. As Parmenides had it, “to gar auto noein estin te kai enai,” “to think and to be are the same thing,” which Heidegger re-interpreted as “to think (learning) and to be (presencing) belong to each other.” (Martin Heidegger, Zähringen Seminar -1973) is (being) is defined as what can be known, and things can only be known through naming – logos, language. By contrast, in the East, “what is” is apprehended through experience. Experience grasps the “that it is” of a thing: “what” the thing is is secondary since it can never be known precisely. Things are constantly changing, and one cannot have names for all the forms they take.

For Aristotle, however, and the West, “To know a thing is to name it, and to name it is to attach one or usually more universal predicates to it. Not only is the fixed within the flow alone knowable, but the universal in the individual as well.” (Robert E Carter, The Nothingness Beyond God, 25-26) To be known is to be named; to be named is to be associated with a universal, for instance, the universal “flower.” When attached to a particular thing in front of me, the universal “flower” tells me that this thing is a flower.

But since flower is a universal, what is really happening is that what a particular thing is is known by using what it has in common with other things: it does not therefore allow a knowledge of the thing as particular, in its uniqueness. Nishida is adamant that Aristotle, whose stated intent was to know things as particular, has failed to achieve his goal. In life, we always encounter particular flowers, never flower as such … Concrete experience is an existential grasp of things as particulars. Aristotle could not get to that point because his thought was shaped by a philosophical tradition which valued the static over the changing. “Greek philosophy considered that which transcends time, the eternal, to be true reality, and, on the contrary, that which moves in time to be imperfect.” (Nishida Kitaro, Fundamental Problems of Philosophy, 39)

Nishida was able to rise above that view by noticing that universals were empty. Already in An Inquiry Into The Good, he notices that colours arise in co-dependence upon each other – for example red in connection with blue, or green, but the very multiplicity of colours points to a universal which is called “colour,” and that universal “colour” itself has to be without colour – that is, it has to be empty of colour – in order to be all the different colours. This led Nishida to the notion that the many arise out of the One, and the One arises out of the many. The One is also Nothingness, since you cannot know the One as One, so the Many naturally arise out of the One/Nothingness, as the world of forms. In the process of the self-expression of Nothingness into the world of forms through the conscious self of the individual, the self-less consciousness of that individual is the basho, or place of nothingness, out of which the world is co-created. The logic whereby all things arise self-contradictorily, is the logic of basho, the place of nothingness, and this is a religious worldview, because it is rooted in self-less self-consciousness, or no-mind. Nishida here appears to have arrived at the exact opposite conclusion to Aristotle’s principle of non-contradiction – a thing cannot be itself and its opposite. In fact Nishida holds that Aristotle’s non-contradiction is correct at the conceptual level, but self-contradictory identity embraces a deeper truth, which includes a grasp from one’s whole self, not by the mind only, but also by the heart, intuition, and the feelings of compassion, benevolence and love, which spontaneously flood one’s apprehension of the world when one empties one’s self.

The standpoint of nothingness envelops the standpoint of being

Nishida’s logic of the place of nothingness, that is, self-contradictory identity, must be seen as a broader more universal logic, which does not stand in opposition to Western philosophy’s ontological objective logic, (“object logic,” as he calls it) as grounded in Aristotle’s principles of reason, but envelops it as it is articulated from the deeper standpoint of no-self. This is the same as saying that one should see all things as “lined with nothingness.

Thirty years ago, before I began the study of Zen, I said, ‘Mountains are mountains, waters are waters.’ After I got an insight into the truth of Zen through the instruction of a good master, I said, ‘Mountains are not mountains, waters are not waters.’ But now, having attained the abode of final rest [that is, Awakening], I say, “Mountains are really mountains, waters are really waters.”

At first, mountains and waters are just mountains and waters, real objects out there in the world. Then, they are no longer mountains and waters, just names. For the awakened, mountains and waters are again mountains and waters, but “lined with nothingness.” Both real objects and names at once, to be seen through the “double aperture,” which is two and at the same time one. This again is the meaning of the title Carter chose for his book on Nishida: The Nothingness Beyond God. The reference here is to Meister Eckhart, whom Nishida read, along with the most significant Christian thinkers, who posited a Godhead he saw as nothingness above God the Creator, acknowledging a deeper Dao-like source of non-being out of which God created the world of being. Nishida’s disciples, Nishitani, Keiji and Ueda, Shizuteru regarded Eckhart as close to Buddhism in his interpretation of Christianity. Ueda spent time in Germany to write a doctoral dissertation on Eckhart. In his last writings, Nishida seems to have hoped that the West finds its own way to his philosophy of nothingness through a recovery of its own religious tradition. He suggested parallels between Christianity and the Pure Land School of Buddhism, which are both devotional, that is, relying on the “other power” of a deity. In Japan, the two paths, Zen’s reliance on “own power,” and Pure Land’s reliance on “other power,” are seen as equally able to lead practitioners to awakening. Could Christianity learn to see itself as the same as Zen? Could philosophy and science see being and reason as enveloped by a broader “religious” logic of the place of nothingness? I wish I could believe that it can happen. The East, however, which has mastered Western ontology and objective thinking, while most of the West is still happy to remain ignorant of Asian nothingness and the concrete experience of actual reality in the present moment, will most probably get there before the West does!

To be religious is to live from the standpoint of emptiness

Nishida goes to great lengths to describe the process whereby ultimate reality, i.e., nothingness, what he also calls the “formless world,” is also dynamic, and self-expresses as the world of forms – the phenomenal/historical world – through the conscious self of each individual, which is a field of nothingness (basho), at once “creating” the world in the present moment, and allowing individuals to become true selves and true individuals. More precisely, the conscious individual selves at all times reflect the world and, as it were, re-process it to match their concrete experience, in a two-way movement which turns individuals collectively into co-creators of the world, not out of any autonomous power, but as conduits for the self-expression of ultimate reality.

In other words, whereas in India, Buddhism tended to contrast the impermanence of illusory phenomena, and the deeper reality of emptiness, presenting awakening as a breaking free from the process of rebirth and a release from the world, in China, and even more so in Japan, reality was seen as change, that is, as such, phenomenal: awakening was simply the realisation that one’s life unfolded in a world of phenomena, which are indeed empty, the forms of the formless. Living in a world of phenomena recognised as being forms empty of own being is living from the standpoint of nothingness. In the Far East, that world of phenomena is a world concretely experienced, lived in its actuality here and now, and impermanence is hailed as activity, dynamism and change: it is life itself. This particular view of the Far East has been referred to as “Asian nothingness” (toyoteki mu).” Whereas the Indian Buddhist anatman (no own being) and Nagarjuna’s sunyata (emptiness) are epistemological concepts – referring to the fact that things are only forms, Asian nothingness refers to a lived experience of reality as a way arising naturally out of nothingness. As Campbell aptly said, India says “All is illusion: let it go,” and China “all is in order, let it come.” In India, enlightenment (samadhi) with the eyes closed, in Japan, enlightenment (satori) with the eyes open. The word moksa (release) has been applied to both, but they are not the same. (Joseph Campbell, The Masks of God – Oriental Mythology, 30-31)

As it welcomed change as an inherent order which should be trusted, China had embarked on a rather involved articulation of the processes of change. In particular, it showed how forms arose as pairs of opposites, symbolised as yin and yang. The Yijing provides a detailed guide of the various configurations which stimulate the diviner’s imagination trying to intuit the unfolding of events in real time. The yin-yang formula constituted the logical system used in various fields, from diet to medicine to architecture to art and of course religious practice.

Present on Nishida’s mind when he articulated his doctrine of “reality as the self-identity of absolute opposites”, for short, “self-contradictory identity” was also the Buddha’s doctrine of co-dependent origination, which can be regarded as the Indian form of the yin-yang logic. In co-dependent origination, all concepts are described as arising in interdependence with each other. This includes an arising in pairs of opposites – short and long, right and left, light and dark, life and death, good and evil. One cannot know what short is unless one also knows what long is. Each step in the process of change is as such a death-life process as the old must “die” to make way for the new. More widely, this includes the interconnectedness of phenomena in nature, how species develop relative to each other, how any occurrence anywhere triggers changes near and far, as everything at all times interacts with everything else.

Western philosophy failed to express the uniqueness of the particular, that which is actually experienced

But, rather than explicitly starting from either yin-yang or co-dependent origination, Nishida turned to Aristotle! This was of course to be expected from a philosopher wishing to use the language of Western philosophy. After Plato, Aristotle is regarded as the founder of metaphysics, the view that reality is Being, as logos, meaning that it is shaped by Ideas, ideal forms existing either in a metaphysical supra-sensory world, or as abstracted from what we see and experience, and as it were, embodied in words. As Parmenides had it, “to gar auto noein estin te kai enai,” “to think and to be are the same thing,” which Heidegger re-interpreted as “to think (learning) and to be (presencing) belong to each other.” (Martin Heidegger, Zähringen Seminar -1973) is (being) is defined as what can be known, and things can only be known through naming – logos, language. By contrast, in the East, “what is” is apprehended through experience. Experience grasps the “that it is” of a thing: “what” the thing is is secondary since it can never be known precisely. Things are constantly changing, and one cannot have names for all the forms they take.

For Aristotle, however, and the West, “To know a thing is to name it, and to name it is to attach one or usually more universal predicates to it. Not only is the fixed within the flow alone knowable, but the universal in the individual as well.” (Robert E Carter, The Nothingness Beyond God, 25-26) To be known is to be named; to be named is to be associated with a universal, for instance, the universal “flower.” When attached to a particular thing in front of me, the universal “flower” tells me that this thing is a flower.