- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

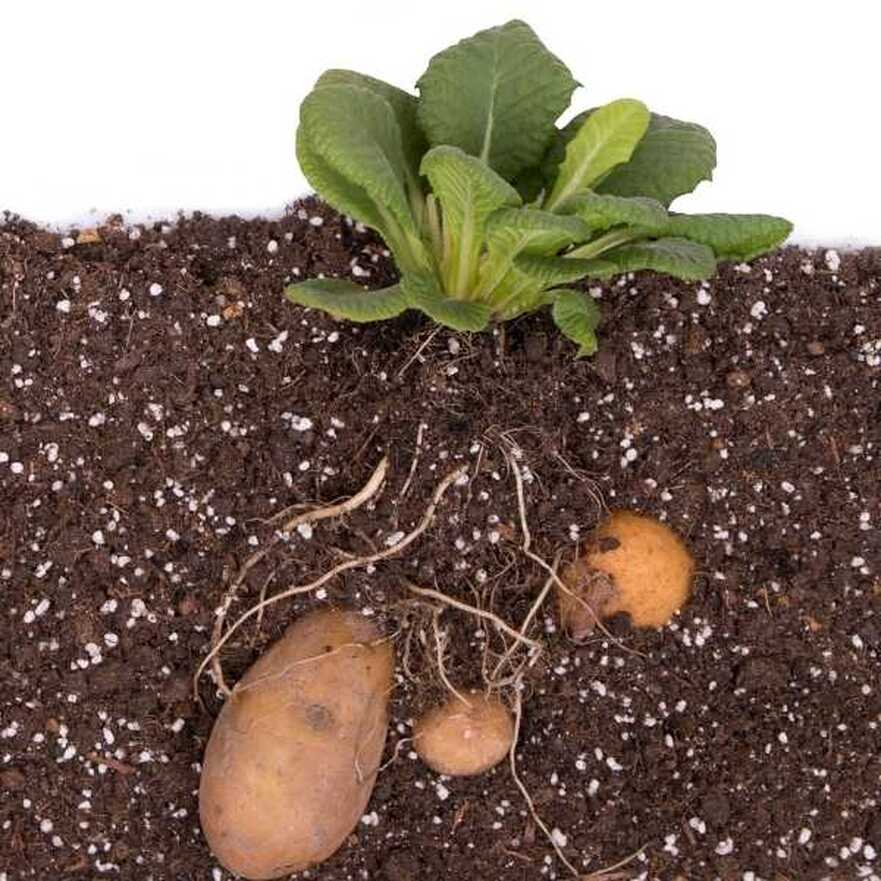

Some people want to be reborn as human beings or spirits. My friend Gwen, a Buddhist, wants to be reborn as a potato. "So much happens underground," she says. She believes the future of the world depends, in part, on whether we can find nourishment from the depths, survive amidst adverse conditions, and provide buds of hope for a world in need, sensitive to the world around us. "Plants are mystics," she says. "Our task is to recognize their gifts and learn from them, reacquainting ourselves with the Deep and then loving our neighbors, all of them, as ourselves.

- Jay McDaniel

- Jay McDaniel

Imitating Potatoes

nutrients, survival, regeneration

The potatoes we eat are not the whole of the potato plant. They are tubers. They develop from an underground stem and act as storage for food/starch for later use by the plant. In fact, the tuber has three main values for the plant:

- Storage of Nutrients: The tuber acts as a storage organ for the plant, storing nutrients such as carbohydrates (in the form of starch), proteins, and other essential compounds. These stored nutrients provide the energy and resources needed for the plant's growth, development, and reproduction.

- Survival during Adverse Conditions: During periods of adverse environmental conditions, such as drought or cold temperatures, the potato plant can rely on the stored nutrients in the tuber to sustain its growth and survival. The tuber acts as a reservoir of energy that can be used when external resources are limited.

- Regeneration: The eyes of the tuber contain dormant buds that can sprout and give rise to new shoots, leading to the growth of new potato plants. This ability to regenerate from the tuber ensures the survival and propagation of the potato plant, especially in regions where conditions may not be favorable for continuous growth from seeds.

Truth be told, these three values are important in human life, too. Spiritually as well as physically, we humans need to store nutrients, whatever nuggets of wisdom we glean from life and the world's wisdom traditions; we need to survive adverse conditions, including climate change, political dysfunction, violence, and obscene gaps between rich and poor; and, where possible, we need to offer regenerative hopes for the world.

It is possible that we have still more to learn from potatoes. Perhaps potatoes are contemplatives in their own right, or mystics. They are aware of their surroundings, including the plants of which they are a part, resting quietly, in dormancy, storing food and starch, awaiting times when if needed, they offer buds for new life. At least so my friend Gwen thinks. She thinks we all ought to be more like potatoes: storing food for the world from the depths of our hearts, and adding buds for new life, while listening to the world around us with contemplative, loving hearts.

- Jay McDaniel

Potatoes as Mystics

Gwen believes in reincarnation. She thinks that after this life, her stream of experiences will continue its journey and inhabit another form, either on this plane of existence or another. She knows that many people think of reincarnation in terms of being reborn as another human being or perhaps as an animal or a spirit, but she adds that she'd like to be reborn as a plant.

"Why?" I ask her. She says that, from her experience, plants combine the best of many virtues. They are very creative and exploratory, but they are also embodiments of peace. She puts it this way: "Many plants I know seem to be at one with their surroundings, they seem relatively content, they are silent witnesses to the world's beauty, and they are part of nature's process of legacy and renewal. They are mystics."

I remind her that there are many kinds of mystics: people who are absorbed in the interior depths of the divine life, people who find the sacred in everyday life, people who are awakened to the interconnectedness of all things, people who feel called to help heal a broken world. She said that most plants she knows are mystics in all of these senses.

I ask her what kind of plant she’d like to be reborn as, and she says "a potato." I ask if she means the entire plant, including its stems, leaves, flowers, and roots, or just the edible part, the potato. She says that the plant as a whole is fine, but she’s particularly keen on the potato: that is, the tubers or bulbs that grow underground. "Potatoes are bodhisattvas," she says. “They are nurturant caregivers for the plants they support and depend on."

She emphasizes that much of this nurturance is underground. She sees an analogy in her own life. So much of what she feels and knows is beneath the surface of conscious sense-experience, and some of this knowing, she suspects, occurs while she is asleep. Gwen has been reading a lot of Jungian psychology these days, which emphasizes that much psychological growth occurs in the unconscious dimensions of our lives; and she's been reading studies in brain science as well, which show that in times of sleep the brain is tremendously active and productive.

During sleep, she reminds me, the brain consolidates memories, processes emotions, and detoxifies by clearing out waste products. It also repairs and restores itself, strengthens neuronal connections, and regulates hormones crucial for overall health. Sleep is essential for cognitive function, emotional well-being, and maintaining brain health. "Potatoes are as active as we are," she says, "and they remind us that ordinary waking consciousness is but the tip of the cognitive and experiential iceberg."

I wonder to myself if she doesn't have a somewhat romantic view of plant life in general and potatoes in particular. She says, "Probably so." But this doesn't bother her. She thinks that imagining ourselves inside the bodies of other creatures inevitably involves projection, and that our imaginations are ways that we connect with the world. “I’m interested in being botanically accurate,” she says, “but also in being spiritually accurate. The truth lies somewhere in between the science and the poetry, ecology and the imagination."

In her view, the whole world would be a better place if we humans imagined ourselves inside other creatures and recognized our kinship with them. "It's a kind of indigenous wisdom," she says. She’s obviously been reading “Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants” by Robin Wall Kimmerer.

Gwen is also a panpsychist. She believes that everything is alive in some way, and that the idea of utterly dead matter is an illusion. Not just the potato plant, but also the soil and the sunshine, the cells and the water, the molecules and atoms. "Everything has its own inner energy; its spontaneity, its own perspective."

I am curious about her use of the word perspective. Does she mean that a potato has a point of view from which it feels the presence of its surroundings? "Yes, and they are capable of enjoying things, too, unconsciously if not consciously." What do they enjoy? "Well, they enjoy being themselves, with all the gurgling that is occurring inside them, and being part of the larger whole." And then she adds, half playfully, "They may even enjoy it when we imagine ourselves inside their skin. They may feel our feelings."

This sounds strange to me. She's obviously been reading some Alfred North Whitehead along with Robin Wall Kimmerer. Not that Whitehead thought potatoes have individual lives of their own, but that, at the very least, they are, in his words, "societies of actual occasions of experience," each occasion of which has a life of its own and "feels the feelings" of other occasions. I ask Gwen if this distinction between actual occasions and societies makes sense to her, and her eyes glaze over. What's important to her is to imagine all living beings, tubers included, as alive with their own inwardness. She's not especially interested in the subtleties of Whitehead's metaphysics.

We turn to the social aspirations of process philosophy. Most process philosophers believe that the best hope of the world is that its societies evolve (quickly) into what they call ecological civilizations. These are civilizations in which people live with respect and care for the community of life. The inhabitants of these communities love one another, to be sure, but they also love other living beings, plants as well as animals.

Gwen proposes that this love can be enriched by what she calls potato theology. Potato theology emphasizes storage, resilience, and regeneration. "It's bulbous in spirit," she says. "And it emphasizes that we can grow even in the darkest of places."

It surprises me a little to hear her use the word "theology," because she is, after all, a Buddhist. But she says that she believes somewhere in the universe - or, actually, everywhere in the universe - there is a nurturing power that is hidden from the eye but regenerative and life-giving. "I sense this power when I sit in the darkness, myself, in meditation. I sense it when I'm gardening. And I sense it among friends, too."

"Do you have a name for that nurturing power?," I ask her. She says that sometimes she does and sometimes she doesn't, but that she trusts it. I ask her what she calls it when she has a name. She says: "Sometimes I call it Silence and sometimes I call it the Deep Underground, but most of the time it's better just to live in it, without naming it, like the potato that lives in the soil, ready to give life."

- Jay McDaniel

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash