- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

The Responsibility of Students

to Be Curious

A Lesson from Confucius

Students, Bring your Corners!

Several years ago, I taught a section of a class required for all incoming students called "Journeys." Its purpose was to introduce students to various ideas and events from around the world that have been a part of the human journey. Different sections of the class were taught by faculty from different departments: by economists, biologists, psychologists, philosophers, and musicians on campus. We didn't claim to be experts in the texts; our goal was to encourage discussion.

During summer workshops, in preparation for teaching, we immersed ourselves in the texts, hoping to gain enough mastery to facilitate informed and dialogical classes. Below, I share one of the Analects of Confucius that ignited much discussion in our workshops.

The Master said, Only one who bursts with eagerness do I instruct; only one who bubbles with excitement, do I enlighten. If I hold up one corner and a student cannot come back to me with the other three, I do not continue the lesson. [1]

All of us teachers, regardless of our fields, resonated with the spirit of the text. We had all encountered students who didn't realize that they, too, shared a responsibility for the success of the class. They, too, needed to bring their "corners."

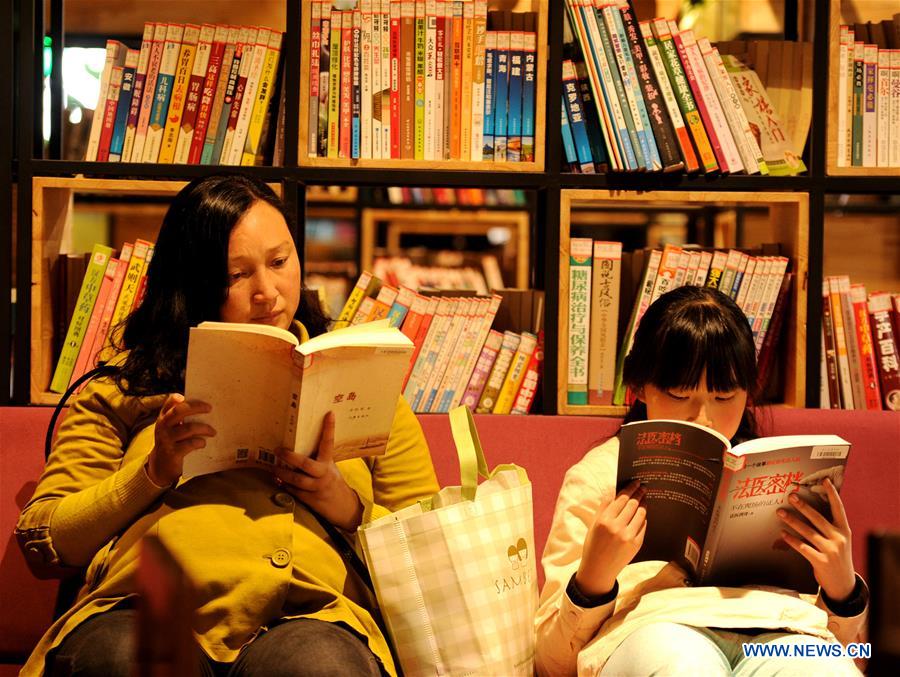

Personally, one of the most engaging discussions I had with students in the Journeys class revolved around this text. On the day we discussed this analect, we discussed and debated the responsibilities of students to bring enthusiasm for learning to class. Some believed that students do have this responsibility; others did not. We all recognized that whether or not a student brings such enthusiasm partly depends on the student's prior experiences in public education and at home. We recognized how fortunate students are whose parents and grandparents embodied a spirit of curiosity and enthusiasm for learning, enabling students to develop a love for learning not only in school but also at home. We realized that, for these students, life itself is very interesting, and that their own desire to learn was rooted in some deep way, not simply in a sense that you are supposed to learn but that learning itself is fun, and that life itself is interesting.

[1] Novak, Philip. The World's Wisdom: Sacred Texts of the World's Religions (p. 115). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

During summer workshops, in preparation for teaching, we immersed ourselves in the texts, hoping to gain enough mastery to facilitate informed and dialogical classes. Below, I share one of the Analects of Confucius that ignited much discussion in our workshops.

The Master said, Only one who bursts with eagerness do I instruct; only one who bubbles with excitement, do I enlighten. If I hold up one corner and a student cannot come back to me with the other three, I do not continue the lesson. [1]

All of us teachers, regardless of our fields, resonated with the spirit of the text. We had all encountered students who didn't realize that they, too, shared a responsibility for the success of the class. They, too, needed to bring their "corners."

Personally, one of the most engaging discussions I had with students in the Journeys class revolved around this text. On the day we discussed this analect, we discussed and debated the responsibilities of students to bring enthusiasm for learning to class. Some believed that students do have this responsibility; others did not. We all recognized that whether or not a student brings such enthusiasm partly depends on the student's prior experiences in public education and at home. We recognized how fortunate students are whose parents and grandparents embodied a spirit of curiosity and enthusiasm for learning, enabling students to develop a love for learning not only in school but also at home. We realized that, for these students, life itself is very interesting, and that their own desire to learn was rooted in some deep way, not simply in a sense that you are supposed to learn but that learning itself is fun, and that life itself is interesting.

[1] Novak, Philip. The World's Wisdom: Sacred Texts of the World's Religions (p. 115). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.

Life Itself is Very Interesting

Every teacher understands the significance of motivating students to learn. We often grapple with the challenge of making our course material interesting if not even, in some instances, captivating. We chose to focus on our particular fields because we ourselves found the material we teach captivating. If we are historians, we love history; if we are physicists, we love physics; if we are economists, we love economics; if we are philosophers, we love philosophy. Indeed, we ourselves may have had our enthusiasm ignited by an effective teacher who likewise found the subject of our inquiry captivating, and who presented it in an engaging way.

Whitehead suggests that effective education should begin not with precision but with romance. In other words, it should involve presenting ideas and information in ways that resonate with students' aptitudes and interests. The presentation hinges not solely on a teacher's engaging style, including enthusiasm for the subject matter, but also on the ability to connect the material with students' real-life experiences. The material must either be genuinely relevant or possess the semblance of relevance to make learning enjoyable, or as Whitehead aptly puts it, "romantic." Precision, the mastery of subject details, can follow this initial spark, not precede it.

However, Confucius reminds us that students, too, bear a significant responsibility—one that is often underestimated, especially in an era where higher education can be reduced to a form of entertainment, with teachers cast as advertisers or marketers of ideas.

According to Confucius, students must enter the classroom with an inherent desire and enthusiasm for learning. Sometimes, to be sure, this eagerness may stem from the belief that the course material aligns with personal goals. A student wants to make money, so he or she takes a course in finance; a student wants to become a physician, so he or she takes a course in organic chemistry; a student wants to help create a more just and sustainable world, so he or she majors in sociology. Yet, relevance alone is insufficient. Students need to arrive at class with a pre-existing enthusiasm for learning, even when the subject matter initially appears uninteresting or not especially relevant to personal goals. It helps if they find life itself interesting. This is what Whitehead believed. He believed that the ultimate subject of education is life itself.

In today's consumer-driven society, where everything is commodified, and individuals, including students, are often seen as mere "consumers" of goods and services, an enthusiasm for learning takes on a counter-cultural significance. It runs counter to the idea that ideas are to be consumed for the sake of other ends, primarily making money. Students embodying a post-consumer spirit not only brings enthusiasm to the classroom but also a desire to expand their horizons—a quality known in process philosophy as having a "wide soul." A wide soul is a person whose sense of self expands by embracing new and unfamiliar ideas. Becoming a wide soul is not about making money or even being "successful" in life. It finds its value in the joy and beauty of learning itself, in soul widening. The process of soul-widening unfolds in the educational context when a student aspires to grow as an individual and recognizes that teachers, whether or not they are entertaining, can be midwives for this growth. The key question here is not, "How can I be entertained?" but rather, "What can I learn?"

Indeed, there is an element of romance in this perspective as well, but it largely hinges on the student's willingness to exercise patience and allow the romance to emerge in the context of the subject matter itself, irrespective of how it is presented by the teacher. Calculus becomes interesting; history becomes interesting; botany becomes interesting; accounting becomes interesting. Nothing is boring.

Even if a student is not particularly inspired by his or her teacher, the student's eagerness to learn remains undiminished. Typically, such eagerness inspires the teacher to become more engaging when possible. I know this first hand. I know that when I sense my students are interested, I become a better teacher - more interesting. However, it remains the student's duty, not the teacher's, to approach each class with a positive attitude—an enthusiasm for learning—regardless of how captivating the teacher may be or how directly the subject matter aligns with personal interests.

For those of us who teach effectively, there is immense gratification in having students who bring this attitude to class. Our students need not bring three corners; even one corner, even a single spark of curiosity, is sufficient. That tiny spark can make all the difference. In such an environment, teaching becomes not just a duty but a source of pleasure and joy. We are more than willing to provide our own corner, to the best of our abilities. Confucius would understand. So would Whitehead. Education becomes relational in the deepest of senses: a meeting of minds, spurred by the mutual assumption that, after all, life itself is very interesting.

- Jay McDaniel