Photo by Chenyu Guan on Unsplash

The Four Harmonies

The ancient Chinese document, the Western Inscription, invites us to orient our lives around four hamonies. At least this is how Haipeng Guo and Jay McDaniel interpret it in the essay following this introduction. The harmonies are:

In each instance the Harmony is fllowing and creative, not stagnant. It is is harmony-in-process. And in each instance the Harmony includes differences, like the diversity of flowers and plants and music in human life.

This emphasis on Harmony as creativity and diversity is relevant even to Harmony with Heaven. The unity of heaven, however understood, is a unity that includes differences. When are 'at one' with Heaven, not when assume and act as if all things must be the same, but when we live with respect for differences as well as similarities, multiplicity as well as unity. Indeed, all things under Heaven and within Heaven are felt and known in their uniqueness, their differences, as beloved members of a larger sacred whole. An appreciation of diversity-in-unity and unity-in-diversity is found in many cultural traditions and many of the world's religions. Consider, for example, the Bahá’í faith which, among the many world religions, highlights Unity most prominently. I borrow the metaphor of flowers, plants, and music, offered above, from The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh.

- Harmony with yourself (harmony between mind and body, inner peace, sincerity, humble self-confidence)

- Harmony with other people (compassionate living: healthy friendships, health family life, healthy neighborhoods)

- Harmony with nature (respect and care for the more than human world, care for animals, eco-communities)

- Harmony with Heaven (a sense of being small but included in a larger sacred whole, a deeper unity)

In each instance the Harmony is fllowing and creative, not stagnant. It is is harmony-in-process. And in each instance the Harmony includes differences, like the diversity of flowers and plants and music in human life.

This emphasis on Harmony as creativity and diversity is relevant even to Harmony with Heaven. The unity of heaven, however understood, is a unity that includes differences. When are 'at one' with Heaven, not when assume and act as if all things must be the same, but when we live with respect for differences as well as similarities, multiplicity as well as unity. Indeed, all things under Heaven and within Heaven are felt and known in their uniqueness, their differences, as beloved members of a larger sacred whole. An appreciation of diversity-in-unity and unity-in-diversity is found in many cultural traditions and many of the world's religions. Consider, for example, the Bahá’í faith which, among the many world religions, highlights Unity most prominently. I borrow the metaphor of flowers, plants, and music, offered above, from The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh.

Consider the flowers of a garden. Though differing in kind, color, form and shape, yet, inasmuch as they are refreshed by the waters of one spring, revived by the breath of one wind, invigorated by the rays of one sun, this diversity increaseth their charm and addeth unto their beauty. How unpleasing to the eye if all the flowers and plants, the leaves and blossoms, the fruit, the branches and the trees of that garden were all of the same shape and color! Diversity of hues, form and shape enricheth and adorneth the garden, and heighteneth the effect thereof. In like manner, when divers shades of thought, temperament and character, are brought together under the power and influence of one central agency, the beauty and glory of human perfection will be revealed and made manifest.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá, The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh, p. 41

In reality all are members of one human family -- children of one Heavenly Father. Humanity may be likened unto the vari-colored flowers of one garden. There is unity in diversity. Each sets off and enhances the other's beauty.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Divine Philosophy, p. 25-26

The diversity in the human family should be the cause of love and harmony, as it is in music where many different notes blend together in the making of a perfect chord. If you meet those of a different race and colour from yourself, do not mistrust them and withdraw yourself into your shell of conventionality, but rather be glad and show them kindness.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá, Advent of Divine Justice, p.32

https://www.openhorizons.org/four-hopes-of-the-process-movement.html

https://www.openhorizons.org/four-hopes-of-the-process-movement.html

As the Bahá’í faith emphasizes, along with many other traditions, Harmony with Heaven is rightly expressed in harmony within yourself, with other people, and with nature. The latter three harmonies come together in the ideal of Ecological Civlization and its image of a nation, indeed a world, consisting of compassionate communities that, together, form a community of communities of communities. A community can be neighborhood, a village, a town, or a city. It is a compassionate community if people know each other and take care of each other, and if they treat other animals and the Earth with respect as well. It is a community that is creative, compassionate, participatory, humane to animals, and good for the Earth, with no one left behind.

The Four Harmonies and Process Philosophy

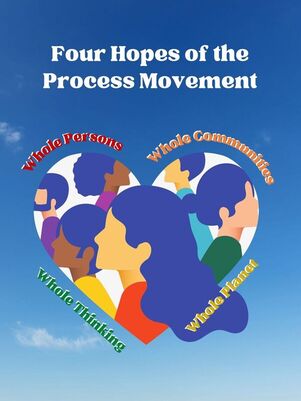

We in the world of process philosophy sometimes speak of our aims as guided by four hopes: (1) Whole Persons, (2) Whole Communities, (3) A Whole Planet, and (4) Whole Thinking that integrates science, art, and spirituality, that recognizes our responsibilities to live with respect and care for the community of life, and that sees all things as interwoven within a sacred whole. The fourth hope - that for holistic or whole thinking -- is in service to the first three. Only if we think in holistic ways, learning from science, art, and spirituality, and thus partaking of many kinds of wisdom, can we help nurture whole personood, whole community, and a whole planet.

The philosophy of Whitehead is one excellent example of Whole Thinking, but there are certainly others. These include so many of the teachings of Bahá’í faith and, for that matter, in an early form the Western Inscription from China.

A short article with only 253 Chinese characters, it was written by Zhang Zai (1020-1077), a Chinese philosopher in Song dynasty. It is considered as one of the most fundamental documents of the Neo-Confucian tradition. It does not speak of the Four Harmonies explicitly, but it implies them implicitly. In our time this message is crucial to the emergence of ecological civilizations and local communities that are its embodiment. This is one of China’s many gifts to the world.

The Four Harmonies and Process Philosophy

We in the world of process philosophy sometimes speak of our aims as guided by four hopes: (1) Whole Persons, (2) Whole Communities, (3) A Whole Planet, and (4) Whole Thinking that integrates science, art, and spirituality, that recognizes our responsibilities to live with respect and care for the community of life, and that sees all things as interwoven within a sacred whole. The fourth hope - that for holistic or whole thinking -- is in service to the first three. Only if we think in holistic ways, learning from science, art, and spirituality, and thus partaking of many kinds of wisdom, can we help nurture whole personood, whole community, and a whole planet.

The philosophy of Whitehead is one excellent example of Whole Thinking, but there are certainly others. These include so many of the teachings of Bahá’í faith and, for that matter, in an early form the Western Inscription from China.

A short article with only 253 Chinese characters, it was written by Zhang Zai (1020-1077), a Chinese philosopher in Song dynasty. It is considered as one of the most fundamental documents of the Neo-Confucian tradition. It does not speak of the Four Harmonies explicitly, but it implies them implicitly. In our time this message is crucial to the emergence of ecological civilizations and local communities that are its embodiment. This is one of China’s many gifts to the world.