- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

What are the fundamental units of human thought? Arguably, they are little sonnets, little songs. We begin with an image, undertake a journey, arrive at a moment of realization, and then the little song perishes, like the concluding couplet of an English sonnet, to be succeeded by other little songs. Maybe thought itself is, deep down, poetic not literal. We don't just think in metaphors, we also think musically. Things have to sound right to us. Maybe theology and philosophy, science and history - maybe they are all little songs. No need to be so literal about everything. No need to pretend that human thought rests on absolutely solid foundations. Maybe it rests on little songs.

*

Whitehead is well-known for proposing that life unfolds in moments, in occasions of experience. A corollary is that our thinking likewise unfolds in moments, which are occasions of thought. Hence, Whitehead's idea is that our experience has a mental pole as well as a physical pole. Occasions of thought would be the mental pole of experience.

The poet and scholar Phillis Levin, editor of "The Penguin Book of the Sonnet," suggests that mental occasions, acts of thinking, are like sonnets. They begin with an idea, undertake a journey, undergo a turning point or a moment of awakening, and then perish, to be succeeded by other such events. The process sounds very much like what Whitehead calls the process of concrescence.

The word "sonnet" literally means "little song." Thus, if Levin is right, her suggestion could be expressed in language that everyone can understand: we think in little songs. Our songs consist of images, journeys, realizations, and endings that inhabit our mental life.

These songs would represent the deeper layer of our thinking. Our songs, our momentary thoughts, begin with bodily experiences, such as breathing, and with memories from the past, from which we derive our images. Here, images can be pictorial, auditory, tactile, or affective. They are, in Whitehead's words, the "objective data" we receive from the past. Influenced and sometimes inspired by these images, we undertake and undergo a journey, seeking momentary insights or realizations, not unlike the end of a sonnet. When our little songs end, they are succeeded by other songs.

This page explores that possibility and some of its implications. Whitehead states in "Process and Reality" that it is more important for a proposition to be interesting than to be true. I do not know if it is "true" that we think in little songs, but I do think it is "interesting." It is also interesting to wonder if more abstract forms of thought - scientific, philosophical, theological, legal, and narrative - might themselves be built of little songs, such that they are little songs added together.

One value of this possibility is that it encourages us to be less legalistic and literalistic than we might otherwise be. Another is that it invites us to consider the possibility that even the clearest thinking may be grounded in something deeper, more bodily, and more amorphous, in little songs that lie just beneath the surface.

Who knows, maybe even the soul of the universe, maybe even God, is an ongoing symphony composed of little songs woven together, such that each song connects with the other, like words on the page of a truly good sonnet. Maybe even God is a sonnet in the making and our lives are the images from which the divine sonnet is being made.

Maybe.

- Jay McDaniel

*

Whitehead is well-known for proposing that life unfolds in moments, in occasions of experience. A corollary is that our thinking likewise unfolds in moments, which are occasions of thought. Hence, Whitehead's idea is that our experience has a mental pole as well as a physical pole. Occasions of thought would be the mental pole of experience.

The poet and scholar Phillis Levin, editor of "The Penguin Book of the Sonnet," suggests that mental occasions, acts of thinking, are like sonnets. They begin with an idea, undertake a journey, undergo a turning point or a moment of awakening, and then perish, to be succeeded by other such events. The process sounds very much like what Whitehead calls the process of concrescence.

The word "sonnet" literally means "little song." Thus, if Levin is right, her suggestion could be expressed in language that everyone can understand: we think in little songs. Our songs consist of images, journeys, realizations, and endings that inhabit our mental life.

These songs would represent the deeper layer of our thinking. Our songs, our momentary thoughts, begin with bodily experiences, such as breathing, and with memories from the past, from which we derive our images. Here, images can be pictorial, auditory, tactile, or affective. They are, in Whitehead's words, the "objective data" we receive from the past. Influenced and sometimes inspired by these images, we undertake and undergo a journey, seeking momentary insights or realizations, not unlike the end of a sonnet. When our little songs end, they are succeeded by other songs.

This page explores that possibility and some of its implications. Whitehead states in "Process and Reality" that it is more important for a proposition to be interesting than to be true. I do not know if it is "true" that we think in little songs, but I do think it is "interesting." It is also interesting to wonder if more abstract forms of thought - scientific, philosophical, theological, legal, and narrative - might themselves be built of little songs, such that they are little songs added together.

One value of this possibility is that it encourages us to be less legalistic and literalistic than we might otherwise be. Another is that it invites us to consider the possibility that even the clearest thinking may be grounded in something deeper, more bodily, and more amorphous, in little songs that lie just beneath the surface.

Who knows, maybe even the soul of the universe, maybe even God, is an ongoing symphony composed of little songs woven together, such that each song connects with the other, like words on the page of a truly good sonnet. Maybe even God is a sonnet in the making and our lives are the images from which the divine sonnet is being made.

Maybe.

- Jay McDaniel

The Sonnet: A Scholarly Discussion

Melvyn Bragg and guests discuss the Sonnet, the most enduring form in the poet’s armoury. For over five hundred years its fourteen lines have exercised poetic minds from Petrarch and Shakespeare, to Milton, Wordsworth and Heaney. It has inspired the duelling verse of ‘sonneteering’, encapsulated the political perspectives of Cromwell and Kennedy and most of all it has provided a way to meditate upon love.Dante Gabriel Rossetti called it “the moment’s monument”. What is it about the Sonnet that has inspired poets to bind themselves by its strictures again and again? With Sir Frank Kermode, author of many books including Shakespeare’s Language; Phillis Levin, Poet in Residence and Professor of English at Hofstra University; Jonathan Bate, King Alfred Professor of English at the University of Liverpool.

The Sonnet is the Way We Think

A Suggestion from Phillis Levin

"The sonnet...not only describes a way of thinking. It is the way we think. For example, when we think about something, say there's an image, often we think about an image and then we come to a realization. We can't control the realization we come to. That's why I think of the volta* as a moment of grace. The volta is the turning point in this song...You begin something, it's a kind of small journey and you know you're going to go somewhere and something's going to change and you don't know what or how it's going to happen but it will happen and you know it's going to end...So I think that's the way we think tends to be we have a kind of amorphousness of ideas. They swim around. then they begin to reach a certain point. Then we reach a conclusion."

Phillis Levine, in interview with Melvyn Bragg of BBC above

* The volta, also known as the "turn," is a point of shift or change in the sonnet where the tone, subject matter, or perspective takes a noticeable turn. It marks a transition from the initial argument or idea presented in the octave (the first eight lines) to the resolution or conclusion in the sestet (the final six lines).

Phillis Levine, in interview with Melvyn Bragg of BBC above

* The volta, also known as the "turn," is a point of shift or change in the sonnet where the tone, subject matter, or perspective takes a noticeable turn. It marks a transition from the initial argument or idea presented in the octave (the first eight lines) to the resolution or conclusion in the sestet (the final six lines).

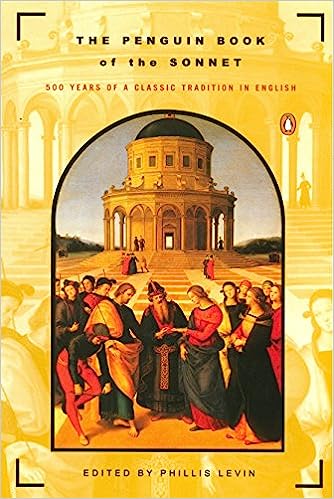

The Penguin Book of the Sonnet

500 Years of Classic Tradition in English

A unique anthology celebrating that most vigorous of literary forms--the sonnet.

The sonnet is one of the oldest and most enduring literary forms of the post-classical world, a meeting place of image and voice, passion and reason, elegy and ode. It is a form that both challenges and liberates the poet.

For this anthology, poet and scholar Phillis Levin has gathered more than 600 sonnets to tell the full story of the sonnet tradition in the English language. She begins with its Italian origins; takes the reader through its multifaceted development from the Elizabethan era to the Romantic and Victorian; demonstrates its popularity as a vehicle of protest among writers of the Harlem Renaissance and poets who served in the First World War; and explores its revival among modern and contemporary poets. In her vibrant introduction, Levin traces this history, discussing characteristic structures and shifting themes and providing illuminating readings of individual sonnets. She includes an appendix on structure, biographical notes, and valuable explanatory notes and indexes. And, through her narrative and wide-ranging selection of sonnets and sonnet sequences, she portrays not only the evolution of the form over half a millennium but also its dynamic possibilities.

The sonnet is one of the oldest and most enduring literary forms of the post-classical world, a meeting place of image and voice, passion and reason, elegy and ode. It is a form that both challenges and liberates the poet.

For this anthology, poet and scholar Phillis Levin has gathered more than 600 sonnets to tell the full story of the sonnet tradition in the English language. She begins with its Italian origins; takes the reader through its multifaceted development from the Elizabethan era to the Romantic and Victorian; demonstrates its popularity as a vehicle of protest among writers of the Harlem Renaissance and poets who served in the First World War; and explores its revival among modern and contemporary poets. In her vibrant introduction, Levin traces this history, discussing characteristic structures and shifting themes and providing illuminating readings of individual sonnets. She includes an appendix on structure, biographical notes, and valuable explanatory notes and indexes. And, through her narrative and wide-ranging selection of sonnets and sonnet sequences, she portrays not only the evolution of the form over half a millennium but also its dynamic possibilities.

Maybe We Think in Little Songs

Whiteheadian meanderings

Sonnet means 'little song.' Phillis Levin, editor of "The Penguin Book of the Sonnet," suggests that the sonnet is more than a way of thinking, it is how we think. We think in little songs.

If this is true, then each little song is a movement of its own, akin to a phrase in a dance. It comes and goes, with some kind of turn, some kind of realization, somewhere in the midst of it.

To be sure, these little songs can also be linked with other songs to form larger narratives. Inside our minds, we are always singing. Nevertheless, the fundamental building blocks of our singing are little songs, akin to the drops of experience of which Whitehead speaks. For Whitehead, such drops are the building blocks of reality: microscopic and macroscopic. He calls them occasions of experience. Perhaps, then, little songs are the building blocks of our thinking, yours and mine. Even our most complex thinking is composed of little songs: occasions of thought with moments of realization, of grace, tucked within them.

Our little songs are momentary, like phrases in a dance. The fourteen lines of a "little song" develop a thought or idea about things that matter: life, love, death, sex, justice, hope, fear, danger, faith, disgust, politics. We craft our little songs in a rhythmic, musical, and concise manner, employing metaphors and analogies, and leading toward momentary conclusions. Some little songs last for only a split second; others for thirty minutes; and some for a whole day. These little songs are our sonnets.

When we think like a sonnet, we are not standing outside the sonnet, observing from a distance. Nor are we merely reading the sonnet as it exists on a page. Instead, we are in the sonnet, engaging in the act of "sonneting." We are a living dewdrop, creating (in Dante's phrase) a monument to the moment. As we create the monument, the monument lies in the immediate future, like the end of a journey. Once created, the monument lies in the past. The present is the act of creating.

As we develop our thought or idea, metaphors and analogies play a central role. They lie at the heart of our sonnetic thinking, interwoven with a sense of rhythm and the sounds of words. The meanings we hold in our minds is inspired not only by the content of the words but also by their sounds. Our little song will make sense to us, if it does at all, because it has a musicality to it. It sounds right.

Our songs are mental but not disembodied. Their lines synchronize with our breath, however shallow or deep, frantic or calm, inevitably drawing upon past experiences. Whitehead calls it experience in the mode of causal efficacy because the past is "efficacious" in the present, a form of lived feeling. Sonnetic songs are always shaped by this kind of experience. They are not created out of nothing. They are created out of amorphous images and feelings, derived from the past actual world.

The lines of our little songs, our sonnets in the moment, are typically not in complete sentences. They are made of sounds, images, words, and ideas. Often, they encompass all these elements, fused together. While pauses occur, there is no punctuation. Punctuation belongs to writing, not to thinking. In the realm of thought, movements flow more fluidly, with the breath serving as the natural punctuation.

There is white space, too. This is the space outside our thinking that provides the environment for the thinking itself. It is pregnant with possibility. We pull from the white space to create our sonnets.

The lines of our momentary sonnets contain clashes and contrasts, which is part of their beauty. The lines will rub against each other, sometimes gently and sometimes violently, creating part of the integrity, maybe even the beauty, of our living song. There can be no music without the contrasts, no sonnets without the rubbing.

We need not interpret the concept of fourteen lines too rigidly. It, too, is a metaphor. You may think in thirteen, fourteen, or fifteen lines, as the precise count is not crucial. Furthermore, please be clear that thinking like a sonnet is not the sole way of thinking. You may also engage in Haiku or explore other poetic forms as modes of thought. Or you may be so distracted that it seems your thoughts have no obvious coherence at all. The flip side of incoherence is imagination, and that is often a very good thing. The building blocks of imagination are little songs that don't exactly fit together, but have their own beauty.

I have several beloved friends who suffer from dementia. Their thought processes are very different from mine, but not at all inferior. We are all in this together. I suspect that they think in little songs, too, but that their songs are less rigidly linked than my own. And often they know things in the heart that are deeper and more profound than we know with our minds. Little songs can emerge when memories come from the heart as well as the head.

In any case, I want to be open to the possibility that much so-called "normal" thinking has a sonnet-like dimension, a musicality to it. Its rigor is musical. Mathematical thinking, scientific thinking, historical thinking, analytical thinking, philosophical thinking— I want to be open to the possibility that, one way or another, we are all thinking with little songs in our minds.

We may not write sonnets, but we think them and perhaps in some ways live them, too. The idea that life is a single narrative is an illusion. It is a series of little songs. Many of them we sing only to ourselves and maybe also to God. Whitehead says that God feels our feelings at every moment. I suspect that God hears our little songs, too: the painful ones and the pleasant ones. God thinks in little songs, too.

- Jay McDaniel

If this is true, then each little song is a movement of its own, akin to a phrase in a dance. It comes and goes, with some kind of turn, some kind of realization, somewhere in the midst of it.

To be sure, these little songs can also be linked with other songs to form larger narratives. Inside our minds, we are always singing. Nevertheless, the fundamental building blocks of our singing are little songs, akin to the drops of experience of which Whitehead speaks. For Whitehead, such drops are the building blocks of reality: microscopic and macroscopic. He calls them occasions of experience. Perhaps, then, little songs are the building blocks of our thinking, yours and mine. Even our most complex thinking is composed of little songs: occasions of thought with moments of realization, of grace, tucked within them.

Our little songs are momentary, like phrases in a dance. The fourteen lines of a "little song" develop a thought or idea about things that matter: life, love, death, sex, justice, hope, fear, danger, faith, disgust, politics. We craft our little songs in a rhythmic, musical, and concise manner, employing metaphors and analogies, and leading toward momentary conclusions. Some little songs last for only a split second; others for thirty minutes; and some for a whole day. These little songs are our sonnets.

When we think like a sonnet, we are not standing outside the sonnet, observing from a distance. Nor are we merely reading the sonnet as it exists on a page. Instead, we are in the sonnet, engaging in the act of "sonneting." We are a living dewdrop, creating (in Dante's phrase) a monument to the moment. As we create the monument, the monument lies in the immediate future, like the end of a journey. Once created, the monument lies in the past. The present is the act of creating.

As we develop our thought or idea, metaphors and analogies play a central role. They lie at the heart of our sonnetic thinking, interwoven with a sense of rhythm and the sounds of words. The meanings we hold in our minds is inspired not only by the content of the words but also by their sounds. Our little song will make sense to us, if it does at all, because it has a musicality to it. It sounds right.

Our songs are mental but not disembodied. Their lines synchronize with our breath, however shallow or deep, frantic or calm, inevitably drawing upon past experiences. Whitehead calls it experience in the mode of causal efficacy because the past is "efficacious" in the present, a form of lived feeling. Sonnetic songs are always shaped by this kind of experience. They are not created out of nothing. They are created out of amorphous images and feelings, derived from the past actual world.

The lines of our little songs, our sonnets in the moment, are typically not in complete sentences. They are made of sounds, images, words, and ideas. Often, they encompass all these elements, fused together. While pauses occur, there is no punctuation. Punctuation belongs to writing, not to thinking. In the realm of thought, movements flow more fluidly, with the breath serving as the natural punctuation.

There is white space, too. This is the space outside our thinking that provides the environment for the thinking itself. It is pregnant with possibility. We pull from the white space to create our sonnets.

The lines of our momentary sonnets contain clashes and contrasts, which is part of their beauty. The lines will rub against each other, sometimes gently and sometimes violently, creating part of the integrity, maybe even the beauty, of our living song. There can be no music without the contrasts, no sonnets without the rubbing.

We need not interpret the concept of fourteen lines too rigidly. It, too, is a metaphor. You may think in thirteen, fourteen, or fifteen lines, as the precise count is not crucial. Furthermore, please be clear that thinking like a sonnet is not the sole way of thinking. You may also engage in Haiku or explore other poetic forms as modes of thought. Or you may be so distracted that it seems your thoughts have no obvious coherence at all. The flip side of incoherence is imagination, and that is often a very good thing. The building blocks of imagination are little songs that don't exactly fit together, but have their own beauty.

I have several beloved friends who suffer from dementia. Their thought processes are very different from mine, but not at all inferior. We are all in this together. I suspect that they think in little songs, too, but that their songs are less rigidly linked than my own. And often they know things in the heart that are deeper and more profound than we know with our minds. Little songs can emerge when memories come from the heart as well as the head.

In any case, I want to be open to the possibility that much so-called "normal" thinking has a sonnet-like dimension, a musicality to it. Its rigor is musical. Mathematical thinking, scientific thinking, historical thinking, analytical thinking, philosophical thinking— I want to be open to the possibility that, one way or another, we are all thinking with little songs in our minds.

We may not write sonnets, but we think them and perhaps in some ways live them, too. The idea that life is a single narrative is an illusion. It is a series of little songs. Many of them we sing only to ourselves and maybe also to God. Whitehead says that God feels our feelings at every moment. I suspect that God hears our little songs, too: the painful ones and the pleasant ones. God thinks in little songs, too.

- Jay McDaniel

The Sonnet

A sonnet is a 14-line poetic form that follows a specific rhyme scheme and meter. It originated in Italy and was popularized by the Italian poet Petrarch in the 14th century. Petrarch's collection of sonnets, known as the "Canzoniere," became highly influential and contributed to the spread of the sonnet form throughout Europe.

The most famous sonnet writers include:

The most famous sonnet writers include:

- William Shakespeare: Shakespeare's sonnets, published in 1609, are among the most well-known and admired in the English language. He wrote 154 sonnets exploring themes of love, beauty, time, and mortality.

- Petrarch: Francesco Petrarca, commonly known as Petrarch, is considered the father of the sonnet. His sonnets were written in Italian and expressed his passionate and unrequited love for Laura, an idealized figure.

- Edmund Spenser: Spenser's collection of sonnets, titled "Amoretti," was published in 1595. It narrates the poet's courtship and eventual marriage to Elizabeth Boyle and is known for its use of intricate imagery.

- John Donne: Donne was an English metaphysical poet who wrote sonnets known for their intellectual and philosophical exploration. His sonnets often blend personal experiences with religious and romantic themes.

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning: Browning's collection, "Sonnets from the Portuguese," published in 1850, is regarded as one of the most celebrated works of Victorian literature. The sonnets chronicle her love for her husband, Robert Browning.

The sonnet's appeal lies in its compact structure and the challenge it presents to the poet. Its strict form, often following a specific rhyme scheme and meter, forces the poet to condense their thoughts and emotions into a limited number of lines. This constraint often leads to the exploration of deep feelings, complex ideas, and the use of vivid imagery. The sonnet's brevity also makes it easily memorable and lends itself to recitation and performance. Its popularity has endured through the centuries due to its versatility and ability to capture a wide range of human experiences.