- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

To Harm or to Heal: the Power of Words

by Teri Daily

|

Moses said: The Lord your God will raise up for you a prophet like me from among your own people; you shall heed such a prophet. This is what you requested of the Lord your God at Horeb on the day of the assembly when you said: “If I hear the voice of the Lord my God any more, or ever again see this great fire, I will die.” Then the Lord replied to me: “They are right in what they have said. I will raise up for them a prophet like you from among their own people; I will put my words in the mouth of the prophet, who shall speak to them everything that I command. Anyone who does not heed the words that the prophet shall speak in my name, I myself will hold accountable. But any prophet who speaks in the name of other gods, or who presumes to speak in my name a word that I have not commanded the prophet to speak—that prophet shall die.”

(Deuteronomy 18:15-20, New Revised Standard Version) |

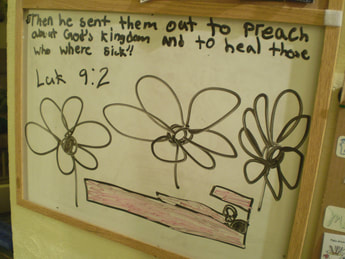

Jesus and his disciples went to Capernaum; and when the sabbath came, he entered the synagogue and taught. They were astounded at his teaching, for he taught them as one having authority, and not as the scribes. Just then there was in their synagogue a man with an unclean spirit, and he cried out, “What have you to do with us, Jesus of Nazareth? Have you come to destroy us? I know who you are, the Holy One of God.” But Jesus rebuked him, saying, “Be silent, and come out of him!” And the unclean spirit, convulsing him and crying with a loud voice, came out of him. They were all amazed, and they kept on asking one another, “What is this? A new teaching—with authority! He commands even the unclean spirits, and they obey him.” At once his fame began to spread throughout the surrounding region of Galilee.

(Mark 1:21-28, New Revised Standard Version) |

Scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright © 1989 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

|

A sermon given on January 28, 2018...

There was a time, not too long ago, when many physicians chose not to speak forthrightly to patients about a diagnosis or prognosis. It seemed kinder and more gentle to withhold, or at least to blur, the whole truth. Times have changed, though, and the important role patients play in treatment decisions is now recognized. It is the patient’s right to know the truth of his or her condition. Still, this doesn’t mean that all ways of explaining that truth are equal. A commentary published by medical professionals explores the various ways physicians explain the diagnosis of heart disease to their patients.[1] Some use ominous terms. You have a lesion in your heart that we call a widow maker. Or you’ve got a ticking time bomb in your chest. Or you flunked your exercise tolerance test. Patients are often already in a very vulnerable position – dressed in a hospital gown, surrounded by an intimidating and sterile setting, stripped of one’s sense of self. And the use of metaphors that further create anxiety or confusion can undermine trust in the patient-physician relationship and leave the patient less capable of rational participation in treatment decisions. Words can harm. However, it doesn’t take much to change the whole dynamics of the physician-patient conversation. According to this same commentary, words that heal do not intensify feelings of dread and doom, or destroy any remnant of hope. Instead, words that heal explain the diagnosis without the use of medical jargon, clarify the priorities of the patient, and enable the patient to fully participate in choosing between treatment options. Words that heal “convey a physician’s compassion, earn the trust of patients, and sustain a bond between equals.” Words can heal. In today’s reading from Deuteronomy, the people need words that heal. They are already starting to worry about what will happen when Moses dies. God gives these reassuring words for Moses to take back to the people of Israel: “I will raise up for them a prophet like you from among their own people; I will put my words in the mouth of the prophet, who shall speak to them everything that I command” (Deuteronomy 18:18, NRSV). The book of Deuteronomy contains stories that circulated by word of mouth from early on in Israel’s history. These stories are believed to have been put together and written down in their present form sometime during the Babylonian Exile. What a comfort this passage must have been to the Jews in exile! There is no longer a temple or a priesthood; the monarchy is defunct; the promised land is taken from them and not even theirs to live in. How can God be with the people now, in this situation? Well, in the word—a word that will spring up from among them. In a time and place where there is no temple or land or kingship that seems to define them as a community, God’s people will be formed by hearing and obeying the word that God sends through the prophets (just as in the time of Moses). But the people were left with a question that still causes us to be perplexed and uncertain, even today: How do we know when someone speaks the word of the Lord? Well, according to verses that immediately follow today’s reading, the Israelites (and we) know a prophet speaks the word of God when that word carries with it power— when the thing spoken of actually comes to pass. It’s the kind of power the people in the synagogue at Capernaum witness in today’s gospel. Jesus and his disciples go to the synagogue on the Sabbath and we’re told that the people are astounded at the authority with which Jesus teaches. A man with an unclean spirit is also present in the synagogue. (It’s important to know that, in the gospel of Mark, having an unclean spirit does not carry a moral judgment. It does not imply that the person is morally corrupt, just that the person is ill or in need.) This man with the unclean spirit cries out: “What have you to do with us, Jesus of Nazareth? Have you come to destroy us? I know who you are, the Holy One of God” (Mark 1:24, NRSV). With one rebuke from Jesus, the spirit leaves the man. Once again, the crowd is amazed, saying “What is this? A new teaching—with authority! He commands even the unclean spirits and they obey him” (Mark 1:27, NRSV). The word translated here as “authority” might actually be better translated as “power.” When Jesus speaks, his word carries power. And for Mark, in particular, the power that Jesus’ word carries is the power to heal. There are eighteen miracles in the gospel of Mark; thirteen of those eighteen miracles are healings. It’s as if Mark is making the point that not only does Jesus’ word carry with it the power to heal, but we know the authority of the word precisely by its ability to heal. After all, God’s power is never separated from God’s love and goodness. We depend on this. We gather in this place week after week for many reasons, but one is that we know the word of God can heal us. It’s interesting that the man with the unclean spirit in today’s gospel story is found within the walls of the synagogue, not outside them. I suspect many of us inside these walls are plagued by our own demons and needs. For some of us these burdens may be physical in nature—illnesses, addictions. Some of us come burdened by sin—the shame of past wrongs, the pain of knowing that we let much in this world pass by without any action on our part, the inability to look past ourselves to see the need of those around us. Maybe we come with an anxiety that consumes us. Or we come with a boredom that springs from doubting that anything new is possible. But we come, because somehow we know that the word of Jesus is a powerful, healing word. We know that true healing requires more than just the cause and effect of medicine or self-help books—it requires actual conversion, newness, transformation. Call it a miracle, if you'd like. The healing we experience in this place is meant to spill over and out into the world. We are to be not only recipients of the healing love of God, but also instruments of it as well. We are to participate in Jesus’ ministry of healing that we see throughout the gospels. Of course, there are times when we don’t get this ministry right—when our words and deeds hurt more than heal, when they foster division instead of reconciliation, when the character of the words we speak lack the authority that comes from love, when our words carry more judgment than mercy. At these times, our words are not what the minister Donna Schaper calls “sacred speech.” She writes: A singular characteristic of sacred speech is its openness. It is humble. It is less interested in being right than in being linked, less interested in self-protection than in self-expression, less interested in cages and doors than in decks and windows. Sacred speech wants clarity and it wants justice. Sacred speech loves a good, honest boundary. But it also wants to maximize love and minimize fear. Sacred speech understands and acknowledges that, in the world that God has made, we need not fear. We may require many fewer locks, keys, borders, and boundaries than we think we do.[2] In other words, sacred speech is speech in service to relationship. This is something ancient monastics have always known. Written in the sixth century as a guideline for life in the monastery, the Rule of Saint Benedict reminds us to communicate with humility—clearly, kindly, without ridicule, choosing to leave some things unsaid to create space for others to speak.[3] Such sacred speech is the key to living life in community, to living a life that brings healing to the hurts of the world. So, in a time in which our world is bombarded by unholy and divisive speech, what might it look like to speak a healing word to the world? Or maybe the more direct question to ask ourselves is simply this: How will what we do and say this week reflect the power of God’s healing love? Will those who come in contact with us know whose we are by the healing power of our words? [1] Susanna E. Bedell MD, Thomas B. Graboys MD, Elizabeth Bedell MA, and Bernard Lown MD, “Words that Harm, Words that Heal.” Archives of Internal Medicine. Volume 164, July 12, 2004. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/571562f1c2ea51227fbd7afd/t/57bccfd4e58c6235ea00d542/1471991765043/Bedell_2004_Arch_of_Int_Med_Words_that_harm_and_heal.pdf. Accessed January 27, 2018. [2] Donna Schaper, Sacred Speech: A Practical Guide for Keeping Spirit in Your Speech (Woodstock, Vermont: Skylight Paths, 2003) 1. [3] A wonderful introduction to Chapter 7 (the chapter on humility) in the Rule of Saint Benedict can be found in John Chittister's book Radical Spirit (New York: Convergent, 2017). |