- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

Imagine that in your own mind you have undergone a conversion from seeing God as an authoritarian figure, preoccupied with reward and punishment, to God as a nurturing force, imbued with care and compassion, and on the side of life. This is the kind of shift described by John Sanders in his book 'Embracing Prodigals: Overcoming Authoritative Religion by Embodying Jesus’ Nurturing Grace,' published by Eerdmans in 2020.

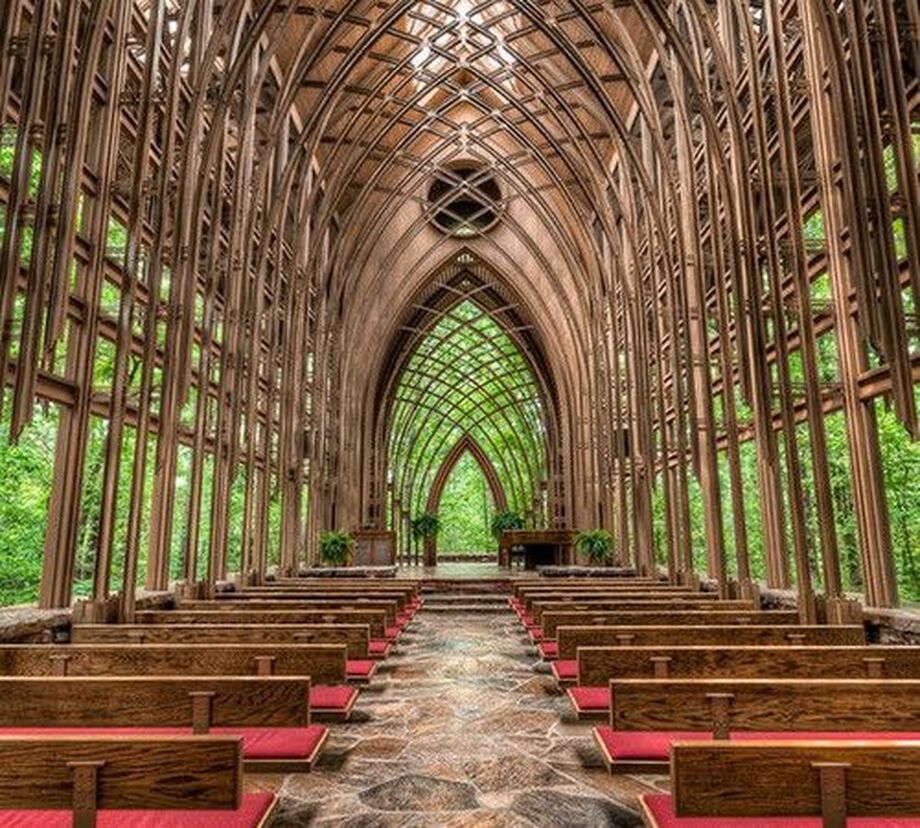

If you have undergone such a shift, you might wonder what worship looks like when worshipping the nurturant power. For some, it might simply mean replacing one image of God in the sky with another, such as shifting from God as King to God as a loving parent, for example. But for others, it may be shifting from experiencing worship as “upward-oriented” toward worship as being held in the presence of a divine, and nurturant, milieu. Here God becomes an encircling presence not easily rendered into a focal object of the imagination. God is better understood as a kind of Light that shines through everything but is more than everything.

This nurturant milieu, this Light, may be mysterious, beautiful, tantalizing, elusive, sometimes confusing, but always safe and caring. It provides a sense of comfort and companionship, but also excites the imagination and gives hope. The milieu can be felt in deeply personal ways, as a 'You' to be addressed in prayer; but it can also be felt as a presence, a force, a power. There is no need to think of this nurturant power as having all the power. There is no need to say that everything that happens “happens” because it's willed or permitted by the nurturant power.

But there is a sense of something more in the universe, independent of you, the worshipper, in the presence of which you stand and sing, kneel and pray, in community with others who do the same. This is worship in an open and relational or process context.

Rowan Williams, an orthodox Christian not a process theologian, puts it well and beautifully, in the paragraphs below, and I am using his language in the paragraph above. The fact that he can experience this presence in the context of traditional liturgies is a healthy reminder that traditional liturgies themselves can be contexts for being standing in the Light. Process oriented Christians need not invent new liturgies; they can rediscover and reclaim inherited liturgies in fresh ways.

When you understand worship as trust in the Light, it is a radical and counter-cultural act because it opens you to something greater than yourself and connects you with others in non-transactional, grace-filled ways. The Light shines upon and within all, without discrimination or preferences. You can cooperate with the spirit and surrender to it, but you cannot control it, nor do you want to do so. Why would anyone want to control Love? Why would anyone want to possess the Light?

Trusting in the Light is especially radical to secularists who think that standing in the presence is a waste of time compared to more practical things related to ambition, problem-solving, or even service to others. Worship undercuts personal ambition because you are pitched into something more and something beautiful than you. Worship is compatible with problem-solving and intellectual inquiry, but in itself, it is not about solving problems or figuring things out. And worship naturally leads to service to others, but in the moment at hand, it is not about helping make the world a better place. It is finding the source, the ground, from which you might want to help make the world a better place in the first place. This momentary contact with others, and often with help from music, liturgy, and a sense of community, is worship.

But there's more to worship than worship. Rowan Williams distinguishes between the worshipping mentality and the act of worship in a special setting. The preceding comments focus on the act of worship, but the mentality, the mindset, is also very important. We can, as best we can, live our waking lives in a worshipful spirit, seeking to be grounded or centered in the light of the nurturant power. This, too, is radical because our frame of reference will not be that of consumer culture. Life will not be about fame, fortune, and power. It will not be about self-proclamation or self-promotion. It will be about something deeper and more lasting: the Love, the Nurturance, the Holy Communion that is possible when we live with others humbly, and in peace. This communion can be felt with other living beings, too, and with the whole of the natural world. The web of life is a sanctuary within which the Light shines. Hills and rivers, trees and stars - they, too, know the Light.

Other people will meet the Light through our listening to them, our caring about them. And we will indeed be of service, but not in ways that point back to us. Our guide will be the Nurturing spirit itself. We can freely say "Not my will by thy will O Love" and be glad in the saying. We do not need to be the center of things.

There is a kind of joy, a rejoicing, in nurturant worship. It is a homecoming. In moments of genuine worship, however fleeting, we are, to quote TS Eliot, arriving at the place we started and knowing it for the first time. Or, to be honest, we are knowing it again for the first time. And again and again. This is why we worship regularly. We want to come home, to be replenished, so that we can go out into the world and be vessels of light in our own small, fragile, beautiful ways. We want to live from the Light.

- Jay McDaniel

If you have undergone such a shift, you might wonder what worship looks like when worshipping the nurturant power. For some, it might simply mean replacing one image of God in the sky with another, such as shifting from God as King to God as a loving parent, for example. But for others, it may be shifting from experiencing worship as “upward-oriented” toward worship as being held in the presence of a divine, and nurturant, milieu. Here God becomes an encircling presence not easily rendered into a focal object of the imagination. God is better understood as a kind of Light that shines through everything but is more than everything.

This nurturant milieu, this Light, may be mysterious, beautiful, tantalizing, elusive, sometimes confusing, but always safe and caring. It provides a sense of comfort and companionship, but also excites the imagination and gives hope. The milieu can be felt in deeply personal ways, as a 'You' to be addressed in prayer; but it can also be felt as a presence, a force, a power. There is no need to think of this nurturant power as having all the power. There is no need to say that everything that happens “happens” because it's willed or permitted by the nurturant power.

But there is a sense of something more in the universe, independent of you, the worshipper, in the presence of which you stand and sing, kneel and pray, in community with others who do the same. This is worship in an open and relational or process context.

Rowan Williams, an orthodox Christian not a process theologian, puts it well and beautifully, in the paragraphs below, and I am using his language in the paragraph above. The fact that he can experience this presence in the context of traditional liturgies is a healthy reminder that traditional liturgies themselves can be contexts for being standing in the Light. Process oriented Christians need not invent new liturgies; they can rediscover and reclaim inherited liturgies in fresh ways.

When you understand worship as trust in the Light, it is a radical and counter-cultural act because it opens you to something greater than yourself and connects you with others in non-transactional, grace-filled ways. The Light shines upon and within all, without discrimination or preferences. You can cooperate with the spirit and surrender to it, but you cannot control it, nor do you want to do so. Why would anyone want to control Love? Why would anyone want to possess the Light?

Trusting in the Light is especially radical to secularists who think that standing in the presence is a waste of time compared to more practical things related to ambition, problem-solving, or even service to others. Worship undercuts personal ambition because you are pitched into something more and something beautiful than you. Worship is compatible with problem-solving and intellectual inquiry, but in itself, it is not about solving problems or figuring things out. And worship naturally leads to service to others, but in the moment at hand, it is not about helping make the world a better place. It is finding the source, the ground, from which you might want to help make the world a better place in the first place. This momentary contact with others, and often with help from music, liturgy, and a sense of community, is worship.

But there's more to worship than worship. Rowan Williams distinguishes between the worshipping mentality and the act of worship in a special setting. The preceding comments focus on the act of worship, but the mentality, the mindset, is also very important. We can, as best we can, live our waking lives in a worshipful spirit, seeking to be grounded or centered in the light of the nurturant power. This, too, is radical because our frame of reference will not be that of consumer culture. Life will not be about fame, fortune, and power. It will not be about self-proclamation or self-promotion. It will be about something deeper and more lasting: the Love, the Nurturance, the Holy Communion that is possible when we live with others humbly, and in peace. This communion can be felt with other living beings, too, and with the whole of the natural world. The web of life is a sanctuary within which the Light shines. Hills and rivers, trees and stars - they, too, know the Light.

Other people will meet the Light through our listening to them, our caring about them. And we will indeed be of service, but not in ways that point back to us. Our guide will be the Nurturing spirit itself. We can freely say "Not my will by thy will O Love" and be glad in the saying. We do not need to be the center of things.

There is a kind of joy, a rejoicing, in nurturant worship. It is a homecoming. In moments of genuine worship, however fleeting, we are, to quote TS Eliot, arriving at the place we started and knowing it for the first time. Or, to be honest, we are knowing it again for the first time. And again and again. This is why we worship regularly. We want to come home, to be replenished, so that we can go out into the world and be vessels of light in our own small, fragile, beautiful ways. We want to live from the Light.

- Jay McDaniel

What is Worship?

Rowan Williams

from his Reith Lecture, 2022

The freedom to spend time in attention to something held to be mysterious, nurturing, elusive and sometimes frustrating, tantalising and inexhaustible: that’s the freedom of worship.

It means the freedom of a contemplative Carmelite nun to gaze in silence at the altar for an hour. The freedom of the Jew on Shabbat. The freedom of a whole community gathered for an hour or two to sing, listen and articulate what is longed for.

It is you could say an extreme version of the freedom we encounter in music or theatre, the freedom that comes from permission not to be useful or productive, but just to be human and to allow that humanity to come for a moment more fully into focus.

For the religious believer such a coming into focus is inseparable from standing in a certain light, trusting in a certain presence, simply looking into a darkness that is paradoxically illuminating and generates new vision.

The secular observer is free to see this as a waste of time, yet limiting or abolishing such timewasting is an essential violent project because it shuts down vital areas of human imagination, the sense of responsibility to something more than naked power, the sense of irony that allows human power to be put into perspective, the sense of hope that reminds us that the way things happen to me today is not set in stone.

And this mixture of responsibility, irony and hope creates what’s been described by one modern philosopher as “a difficult liberty, the freedom to keep alert to the double dangers of modernity.” One danger is the dominance of an external authority that claims universal and final rationality, the authority at worst of fascism and communism. And the other danger is the sanctifying of an inner authority of individual authenticity and ambition.

Religious liberty, the freedom of worship helps to make political liberty difficult in this constructive and good sense. When it fully understands what it’s about it will not be looking for a religious consensus which itself can become an agent of coercion and control, it will simply seek to leave the question there for the human imagination.

What if there are priorities radically unconcerned with success or profit or popularity? What if the deepest human dignity is visible in the sovereign freedom to adore and delight? What would human society look like if that were true? Difficult, yes, but what if the alternative is the frozen conformity of some imagined end of history where no unsettling moral questions could ever be asked?

It means the freedom of a contemplative Carmelite nun to gaze in silence at the altar for an hour. The freedom of the Jew on Shabbat. The freedom of a whole community gathered for an hour or two to sing, listen and articulate what is longed for.

It is you could say an extreme version of the freedom we encounter in music or theatre, the freedom that comes from permission not to be useful or productive, but just to be human and to allow that humanity to come for a moment more fully into focus.

For the religious believer such a coming into focus is inseparable from standing in a certain light, trusting in a certain presence, simply looking into a darkness that is paradoxically illuminating and generates new vision.

The secular observer is free to see this as a waste of time, yet limiting or abolishing such timewasting is an essential violent project because it shuts down vital areas of human imagination, the sense of responsibility to something more than naked power, the sense of irony that allows human power to be put into perspective, the sense of hope that reminds us that the way things happen to me today is not set in stone.

And this mixture of responsibility, irony and hope creates what’s been described by one modern philosopher as “a difficult liberty, the freedom to keep alert to the double dangers of modernity.” One danger is the dominance of an external authority that claims universal and final rationality, the authority at worst of fascism and communism. And the other danger is the sanctifying of an inner authority of individual authenticity and ambition.

Religious liberty, the freedom of worship helps to make political liberty difficult in this constructive and good sense. When it fully understands what it’s about it will not be looking for a religious consensus which itself can become an agent of coercion and control, it will simply seek to leave the question there for the human imagination.

What if there are priorities radically unconcerned with success or profit or popularity? What if the deepest human dignity is visible in the sovereign freedom to adore and delight? What would human society look like if that were true? Difficult, yes, but what if the alternative is the frozen conformity of some imagined end of history where no unsettling moral questions could ever be asked?

Rowan Williams Reith Lecture

Rowan Williams, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, gives the second of the 2022 Reith Lectures, discussing faith and liberty. Please find the lecture above. In his lecture, he cites Lord Acton, the 19th Century thinker on freedom, who said that religious freedom is the basis of all political freedom. Most of what he talks about is the relation of the worshipping mentality to the world today, how its very conviction that human beings can be attuned to moral values beyond themselves, is essential to democracy. At the end he addresses the question of what worship as a time of meeting, of being in a space, of gathering. The worshipping of which he speaks can be Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist or still other. It takes a person to a place that is mysterious, nurturing, elusive, sometimes frustrating, tantalizing and inexhaustible. It helps a person become centered in something good, something nurturing, beyond themselves, and it is rightly translated or manifest in their daily life. In the moment of worship, he says, a person stands in a certain light. This standing in a presence, he adds, is an extreme version of what people may also experience in music and theatre. This kind of worship that may seem a waste of time to secular people, but it replenishes the soul, in community with others, and perspective giving.