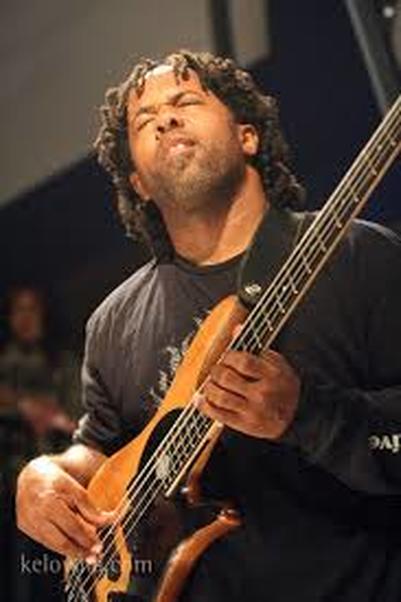

Victor Wooten

Connections between Ecotheology and Music

Music with an upper Case M |

Make Music Not War |

|

|

|

Victor Wooton's Ecotheology

an interpretation by Jay McDaniel

Victor Wooten is a five-time Grammy winner, bass guitarist, husband and father, and coordinator of a Center for Music and Nature in Tennessee. He doesn't think of himself as a process theologian or an ecotheologian, but I think of him this way. Here's why. He sees himself and all others as part of, not apart from, the more-than-human world; he believes that all entities are alive (vibrating) in one way or another; he believes that making music and living with respect for life and environment go together; he finds touches of transcendence in music, plants, animals, and people; he believes in a divine Lure at work in the world, not all powerful but all-inspiring, who presents herself in human-like terms, beckoning us to live with compassion and creativity. Sure sounds like process theology to me. Process theologians speak of this Lure as "God" and Victor Wooten calls her as "Music." Both are good names; see Theology from a Jazz Bar. If we take a music lesson from Victor Wooten, I think it goes something like this:

The Music Lesson

1. Learning to play an instrument can be a spiritual practice. We don't need to be experts to learn. We can learn to play in the same way that we learned to speak as children: by experimenting, joining in, and embracing our mistakes.

2. Even if we aren't musicians, we are called to dwell musically in the world. Music is a lifestyle and not simply a language. Practicing the lifestyle does not require that we listen to music all the time. Instead we listen to the voices of other people and the natural world as if they were music and then respond by trying to make music with them, adding beauty of our own. The beauty we add can be a kind word to a friend, offering a helping hand to a stranger, caring for animals, or dancing barefoot in the moonlight. Whenever we act in the world in healing ways we are adding a moment of beauty to the world, a scrap of light, a fresh melody. Even justice is an act of music-making, a kind of harmony.

3. The basic question of our lives is "What does the world need from me?" Consumerism asks: "What can I get from the world?" This is to put ourselves at the center and make everything else a satellite. It is much better to approach the world humbly and creatively: that is, lovingly. We find our own fulfillment in working with other people and the natural world, in a spirit of musical rapport.

4. The hills and rivers, trees and stars, play music, too. Everything is interconnected and vibrating all the time. The whole of the universe is an ongoing act of improvisation. This does not mean that the world is always pretty. Witness the violence and greed and despair. Witness the loss of life and the absence of love. There is too much unspeakable suffering, and too much missed potential, to say that the world is an ode to joy. Nevertheless, the world is music-like in that it is a fluid and evolving process composed of events that come into existence and then pass away, like musical notes of varying durations in an ongoing concert. Mountains are events, rivers are events, and people are events. Some events last longer than others but all arise and then perish. And each event is a blending of influences from other sources. In its creativity it transcends the strict determinism of the past. It displays what the Chinese call a continuous creativity – a qi – which is always here and now, always spontaneous, and always expressing itself in the sheer as-it-is-ness of whatever is.

5. God - the Soul of the Universe who beckons us to dwell musically -- is Music personified. God is the poet of the world, spiritual but natural, who operates through love not compulsion, luring each and every human being to live in a spirit of wisdom, compassion, and creativity. God can be known and felt as a personal presence (a mother, a father, a lover) but also as an energy or consciousness: that is, as Love, Emotion, Beauty, Expression, Harmony, Communication, Nature, and Vibrations. Music as presented by Wooten might well be another name for God, and a very good one.

That's enough to get started. Victor Wooten invites us to recognize that the arts have a profound importance to ecotheology and that the vocation of the artist, among other things, can be to be present lures for feeling and understanding that help us live kindly with each other, gently with animals, and lightly on the earth, for the sake of spirit and nature. What to do first? Pick up a bass guitar and start playing.

an interpretation by Jay McDaniel

Victor Wooten is a five-time Grammy winner, bass guitarist, husband and father, and coordinator of a Center for Music and Nature in Tennessee. He doesn't think of himself as a process theologian or an ecotheologian, but I think of him this way. Here's why. He sees himself and all others as part of, not apart from, the more-than-human world; he believes that all entities are alive (vibrating) in one way or another; he believes that making music and living with respect for life and environment go together; he finds touches of transcendence in music, plants, animals, and people; he believes in a divine Lure at work in the world, not all powerful but all-inspiring, who presents herself in human-like terms, beckoning us to live with compassion and creativity. Sure sounds like process theology to me. Process theologians speak of this Lure as "God" and Victor Wooten calls her as "Music." Both are good names; see Theology from a Jazz Bar. If we take a music lesson from Victor Wooten, I think it goes something like this:

The Music Lesson

1. Learning to play an instrument can be a spiritual practice. We don't need to be experts to learn. We can learn to play in the same way that we learned to speak as children: by experimenting, joining in, and embracing our mistakes.

2. Even if we aren't musicians, we are called to dwell musically in the world. Music is a lifestyle and not simply a language. Practicing the lifestyle does not require that we listen to music all the time. Instead we listen to the voices of other people and the natural world as if they were music and then respond by trying to make music with them, adding beauty of our own. The beauty we add can be a kind word to a friend, offering a helping hand to a stranger, caring for animals, or dancing barefoot in the moonlight. Whenever we act in the world in healing ways we are adding a moment of beauty to the world, a scrap of light, a fresh melody. Even justice is an act of music-making, a kind of harmony.

3. The basic question of our lives is "What does the world need from me?" Consumerism asks: "What can I get from the world?" This is to put ourselves at the center and make everything else a satellite. It is much better to approach the world humbly and creatively: that is, lovingly. We find our own fulfillment in working with other people and the natural world, in a spirit of musical rapport.

4. The hills and rivers, trees and stars, play music, too. Everything is interconnected and vibrating all the time. The whole of the universe is an ongoing act of improvisation. This does not mean that the world is always pretty. Witness the violence and greed and despair. Witness the loss of life and the absence of love. There is too much unspeakable suffering, and too much missed potential, to say that the world is an ode to joy. Nevertheless, the world is music-like in that it is a fluid and evolving process composed of events that come into existence and then pass away, like musical notes of varying durations in an ongoing concert. Mountains are events, rivers are events, and people are events. Some events last longer than others but all arise and then perish. And each event is a blending of influences from other sources. In its creativity it transcends the strict determinism of the past. It displays what the Chinese call a continuous creativity – a qi – which is always here and now, always spontaneous, and always expressing itself in the sheer as-it-is-ness of whatever is.

5. God - the Soul of the Universe who beckons us to dwell musically -- is Music personified. God is the poet of the world, spiritual but natural, who operates through love not compulsion, luring each and every human being to live in a spirit of wisdom, compassion, and creativity. God can be known and felt as a personal presence (a mother, a father, a lover) but also as an energy or consciousness: that is, as Love, Emotion, Beauty, Expression, Harmony, Communication, Nature, and Vibrations. Music as presented by Wooten might well be another name for God, and a very good one.

That's enough to get started. Victor Wooten invites us to recognize that the arts have a profound importance to ecotheology and that the vocation of the artist, among other things, can be to be present lures for feeling and understanding that help us live kindly with each other, gently with animals, and lightly on the earth, for the sake of spirit and nature. What to do first? Pick up a bass guitar and start playing.

Addendum

What is Ecotheology, Anyway?

Ecotheologian. Someone who presents ideas and possibilities -- lures for feeling and understanding -- aimed at helping people live kindly with one another, gently with animals, and lightly on the earth, for the sake of human beings and the entire community of life.

Media for Ecotheology. Words (written and spoken), music, visual arts, dance, film, theater, and liturgy.

Sources for Ecotheology. Hills, rivers, trees, stars, friends, family, poems, essays, paintings, movies, mentors, social problems, and life circumstances, pleasant and painful.

Contexts for Ecotheology: (1) global climate change, social injustices, war and threat of nuclear war, economic inequality, political repression, and cultural despair; (2) the existential need on the part of human beings to enjoy rich connections with the more-than-human world.

Three Dimensions of Ecotheology. Understanding (beliefs about the nature of the universe and what is ultimately real), action (individual acts of service to people, animals, and the earth as well as political action and advocacy) and spirituality (sense of connectedness, wonder and awe, trust in beauty).

What is theological about Ecotheology? The theological side of ecotheology is its spirituality. Eco-spirituality consists of respect and care for the community of life, a sense of being small but included in a larger whole, sensitivity to individual human beings and other animals as subjects of their own lives (not simply objects for others), delight in multiplicity, and gratitude for beauty. It can involve belief in God, understood as a personal presence active in the world who is more than the world, or as a felt energy that pervades the universe and connects all things.

Beauty. Beauty is the heart of the spiritual side of ecotheology. Beauty is felt in the natural world, in the poignancy of human relationships, and in music and the arts. It is what sustains the action and part of what informs the understanding.

Spiritual Practices. Spiritual practices in ecotheology can include prayer, meditation, gardening, running, and, as Victor Wooten makes clear, learning to play a musical instrument.

Nature and its Three Meanings. Nature is important in ecotheology. The word "nature" can mean (a) the web of life on earth, including human beings, or the Earth Community; (b) the universe as a whole, including its galactic dimensions, understood as an ongoing and unfinished journey, also called The Universe Journey; and (c) the more-than-human world on earth: plants, animals, minerals, waterways, land forms, geological formations and, if they exist, earth spirits. Many ecotheologians find each of these meanings important; see Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim: Emerging Earth Community.

World Loyalty. The Earth Community is the web of life on earth, including its biosphere. Ecotheologians encourage us to live in a way that is loyal to life on Earth even as it might also be loyal to their local region, religion, or ethnicity. The philosopher Whitehead calls this world loyalty.

Integral Ecology. Pope Francis' name for a state of affairs in which care for people, care for animals, and care for the earth are integrated. Integral includes the subjective side of life (eco-spirituality) and the objective side of life (governance, economics, public policy).

The Poor. Those who think in terms of 'integral ecology' have a special concern for poor, powerless, and otherwise marginalized human beings who are among the first to suffer from environmental degradation, political repression, and violence.

Eco-Justice. The human side of integral ecology. A state of affairs in which human beings freely participate in the decisions that affect their lives; with ample opportunities for life, liberty, education, health care, and happiness. They are free from fear and free to enjoy rich bonds with other human beings and the more-than-human world.

Shallow Environmentalism. Neglects integral ecology by focusing solely on the rights and needs of the more-than-human world.

Incomplete Social Justice Activism. Neglects integral ecology by focusing solely on the rights and needs of human beings, neglectful of the more-than--human world and the way in which the human poor suffer from environmental problems.

Ethical ideal. The guiding ethical ideal of Ecotheology is to live with respect and care for the community of life, human beings included, and with special care for the poor and powerless. The phrase "respect and care for the community of life" comes from the Earth Charter.

Obstacles to Ecotheology: (1) consumerism, (2) anthropocentrism, (3) patriarchy, (4) western individualism, (5) dualisms that draw sharp distinctions between humanity and the web of life, and (6) mechanistic worldviews that reduce the whole of reality to a machine for human use. Human greed and the will-to-power play important roles as well, but they are fed by these cultural and intellectual factors.

Religion. Religion can be a powerful source for constructive ecotheology and also an obstacle to ecotheology. There are many helpful ideas and practices in the various traditions and also many harmful ideas and practices. The best source for seeing both sides is the Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology. Many ecotheologians with religious affiliations seek to be honest about both sides, with the assumption that their traditions can change and grow over time. There can be progress, even in religion.

Media for Ecotheology. Words (written and spoken), music, visual arts, dance, film, theater, and liturgy.

Sources for Ecotheology. Hills, rivers, trees, stars, friends, family, poems, essays, paintings, movies, mentors, social problems, and life circumstances, pleasant and painful.

Contexts for Ecotheology: (1) global climate change, social injustices, war and threat of nuclear war, economic inequality, political repression, and cultural despair; (2) the existential need on the part of human beings to enjoy rich connections with the more-than-human world.

Three Dimensions of Ecotheology. Understanding (beliefs about the nature of the universe and what is ultimately real), action (individual acts of service to people, animals, and the earth as well as political action and advocacy) and spirituality (sense of connectedness, wonder and awe, trust in beauty).

What is theological about Ecotheology? The theological side of ecotheology is its spirituality. Eco-spirituality consists of respect and care for the community of life, a sense of being small but included in a larger whole, sensitivity to individual human beings and other animals as subjects of their own lives (not simply objects for others), delight in multiplicity, and gratitude for beauty. It can involve belief in God, understood as a personal presence active in the world who is more than the world, or as a felt energy that pervades the universe and connects all things.

Beauty. Beauty is the heart of the spiritual side of ecotheology. Beauty is felt in the natural world, in the poignancy of human relationships, and in music and the arts. It is what sustains the action and part of what informs the understanding.

Spiritual Practices. Spiritual practices in ecotheology can include prayer, meditation, gardening, running, and, as Victor Wooten makes clear, learning to play a musical instrument.

Nature and its Three Meanings. Nature is important in ecotheology. The word "nature" can mean (a) the web of life on earth, including human beings, or the Earth Community; (b) the universe as a whole, including its galactic dimensions, understood as an ongoing and unfinished journey, also called The Universe Journey; and (c) the more-than-human world on earth: plants, animals, minerals, waterways, land forms, geological formations and, if they exist, earth spirits. Many ecotheologians find each of these meanings important; see Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim: Emerging Earth Community.

World Loyalty. The Earth Community is the web of life on earth, including its biosphere. Ecotheologians encourage us to live in a way that is loyal to life on Earth even as it might also be loyal to their local region, religion, or ethnicity. The philosopher Whitehead calls this world loyalty.

Integral Ecology. Pope Francis' name for a state of affairs in which care for people, care for animals, and care for the earth are integrated. Integral includes the subjective side of life (eco-spirituality) and the objective side of life (governance, economics, public policy).

The Poor. Those who think in terms of 'integral ecology' have a special concern for poor, powerless, and otherwise marginalized human beings who are among the first to suffer from environmental degradation, political repression, and violence.

Eco-Justice. The human side of integral ecology. A state of affairs in which human beings freely participate in the decisions that affect their lives; with ample opportunities for life, liberty, education, health care, and happiness. They are free from fear and free to enjoy rich bonds with other human beings and the more-than-human world.

Shallow Environmentalism. Neglects integral ecology by focusing solely on the rights and needs of the more-than-human world.

Incomplete Social Justice Activism. Neglects integral ecology by focusing solely on the rights and needs of human beings, neglectful of the more-than--human world and the way in which the human poor suffer from environmental problems.

Ethical ideal. The guiding ethical ideal of Ecotheology is to live with respect and care for the community of life, human beings included, and with special care for the poor and powerless. The phrase "respect and care for the community of life" comes from the Earth Charter.

Obstacles to Ecotheology: (1) consumerism, (2) anthropocentrism, (3) patriarchy, (4) western individualism, (5) dualisms that draw sharp distinctions between humanity and the web of life, and (6) mechanistic worldviews that reduce the whole of reality to a machine for human use. Human greed and the will-to-power play important roles as well, but they are fed by these cultural and intellectual factors.

Religion. Religion can be a powerful source for constructive ecotheology and also an obstacle to ecotheology. There are many helpful ideas and practices in the various traditions and also many harmful ideas and practices. The best source for seeing both sides is the Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology. Many ecotheologians with religious affiliations seek to be honest about both sides, with the assumption that their traditions can change and grow over time. There can be progress, even in religion.