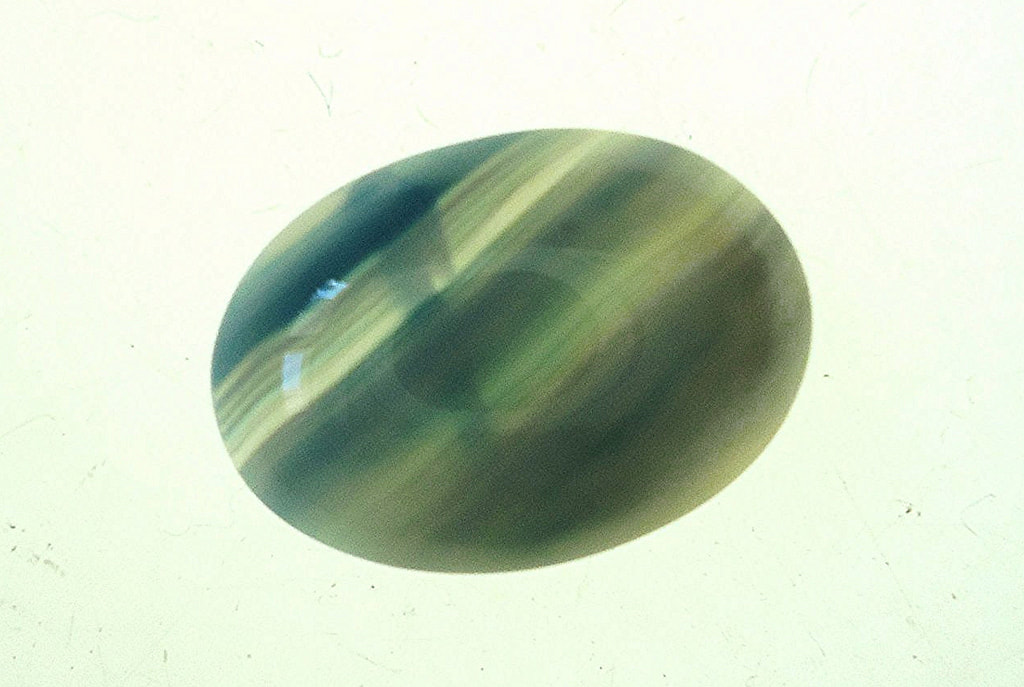

Carrying the Names

of those engraved in the jewelry of the heart

as a daily practice inspired by Torah

|

The practice: Keep an index card by your bedstand. In the morning when you get up, write the name of a person who, in a positive way, has helped make you "you" at this time in your life. Let a feeling of gladness arise in your heart: not just gladness for the positive role they played in your life but also gladness for their existence independent of you. Celebrate their you-ness. Choose a different person every morning. Do it for one year. Then do it the following year, too. And the one after that.

Additional advice: Choose people for whom you feel affection but also people who irritate you. Also, in humility, include people whom you have treated unkindly. You need not be grateful for your unkindness, but you can be grateful for their lives and presence in the world. Put a check by their names and contact them, trying to make amends. Tell them you love them and act on it. |

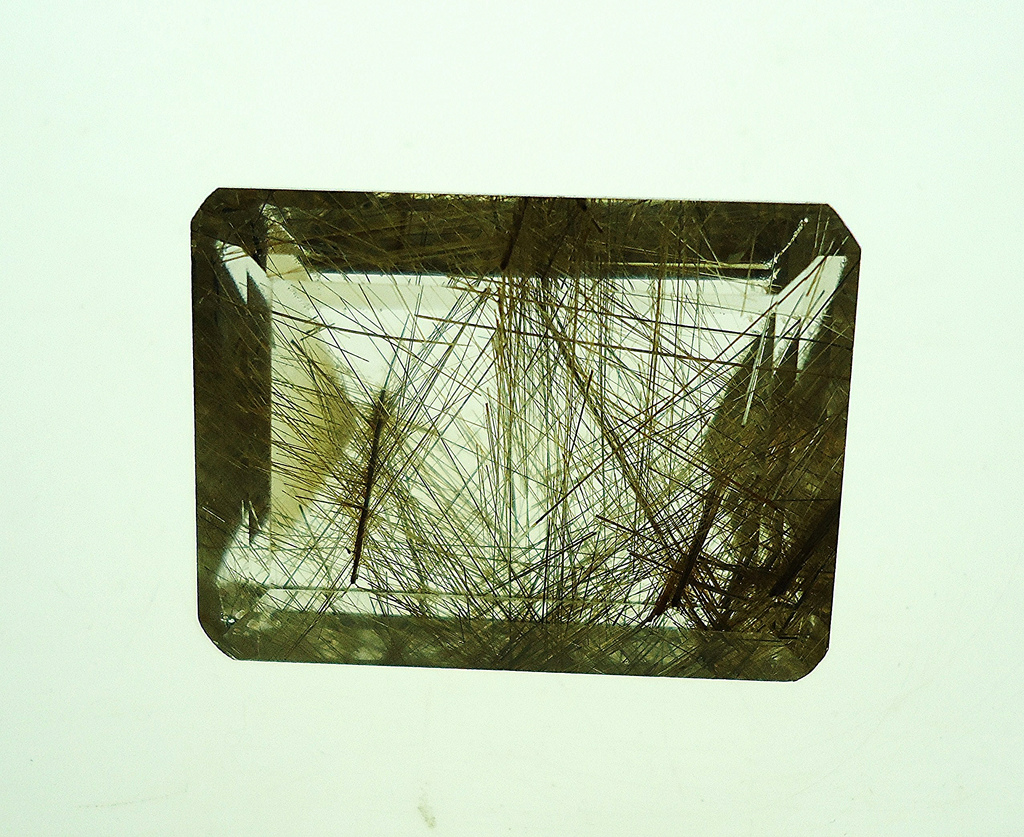

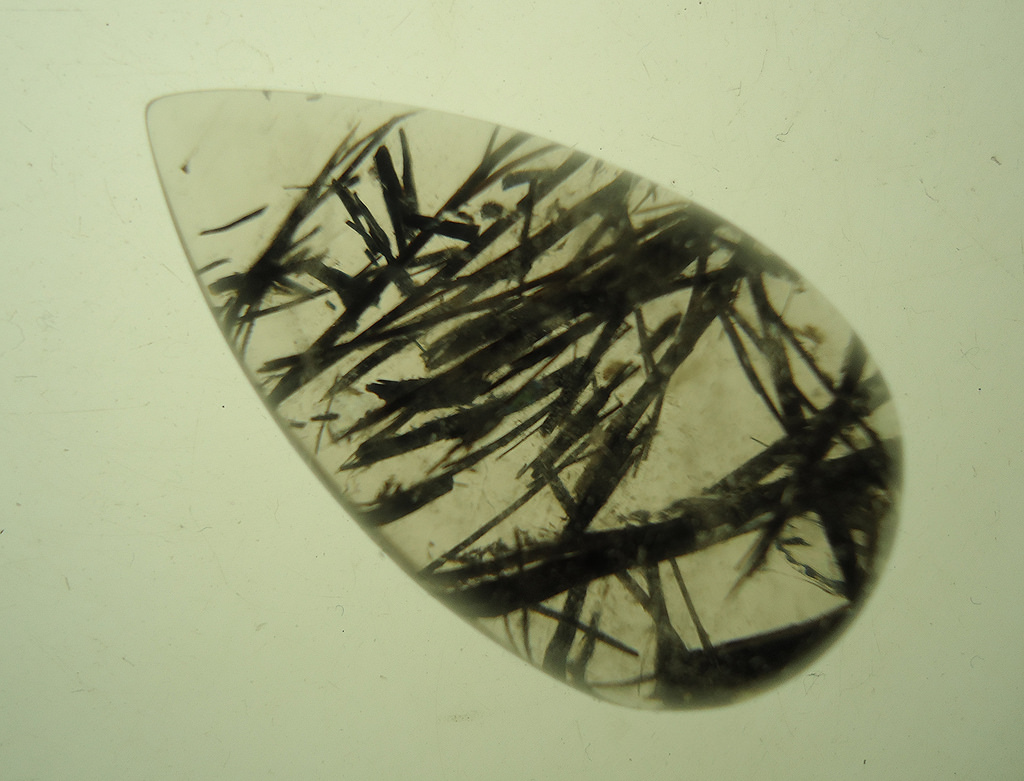

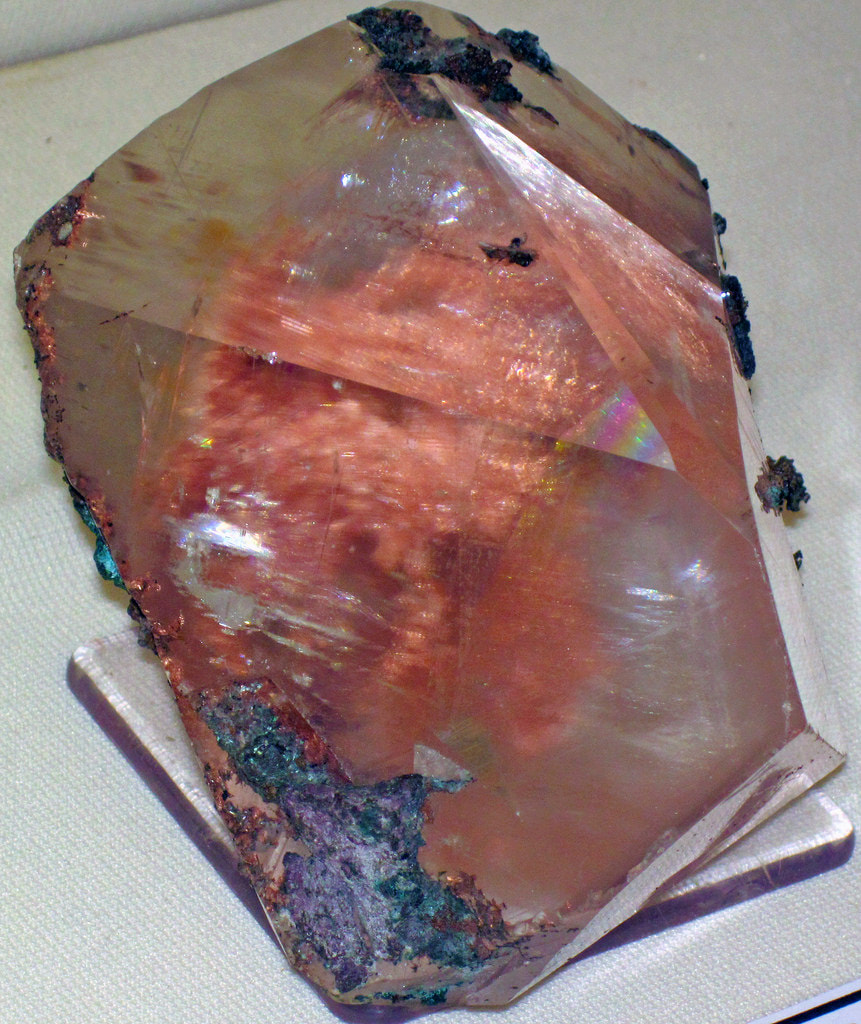

A Midrash on Rabbi Artson's "Moment of Torah"It is 6:30 am. The sun is rising; and I have recently risen as well. I've begun the day as I often do, with a Moment of Torah offered by Rabbi Bradley Artson. Today he is commenting on a passage at the end of the book of Exodus, where a garment to be worn by priests called the Ephod is described. The stones of the garment carry the names of the twelve tribes of Israel. He compares the names on the stones to the names of those whom we carry in our hearts.

Thank You Notes I would like to write a thank you note to each person who has made it possible for me to rise this morning, and whose name is engraved, consciously or unconsciously, in the jewelry of my own heart. This would include my mother and father, gas station attendants and grocery store clerks; Elvis Presley and Bob Dylan; classmates in elementary school and college students I taught at Hendrix College for 39 years; the hospice care nurses who took care of my mother and Betty who sat on the front row of the assisted living center where I played music last night. It would also include strangers in airports, with whom I've had momentary but meaningful conversations. And it would include the bully down the street when I grew up, who through mudballs at me, but who taught me to be brave. It would also include, people who've helped me become "me," but to whom, unfortunately, I've been unkind or neglectful. There would be no "me" to rise this morning, without them. Each thank you note would be different, tailored to the uniqueness of the circumstances in which we knew each other. Some would say "thank you" pure and simple, and some would add, and I'm so sorry I didn't treat you kindly or haven't been in touch. I know it will take a long time to write these notes. One lifetime is reallly not enough. If there's a continuing journey after death, maybe its purpose: to write thank you notes. But I'll begin now, making sure I can thank and make amends to those among the living. I know this is what Rabbi Artson would counsel me to do. Judaism focusses on what we do in this life. That's part of its beauty. Process Theology Rabbi Artson is one of the world's leading process theologians, so he's influenced not only by Torah but also by Whitehead. Whitehead believed that at every moment of our lives we are formed or "composed" of all the people and other living beings -- indeed all the entities of whatever kind -- that we have encountered consciously or unconsciously. They are actually "present in" us even as they are also more than us. They are. in Whitehead's words, "the many that become one" in our experience. This Whiteheadian idea, almost Buddhist in tone, has implications for how we understand ourselves and live in the world. It is an illusion to think that we are skin-encapsulated egos cut off from the world by the boundaries of our skin. Our very selves, moment by moment, are composed of the people we experience and respond to. We "carry their names" within us -- and something of their energy along with their names. The Jewelry of God's Heart Of course, when we thank them, we are not simply grateful for what they've done for us. We are glad that they are, pure and simple, quite apart from how they've helped us. Glad for their you-ness. In their spiritual alphabet Mary Ann and Frederic Brussat speak of a spiritual practice called You. Here's what they say: Each of us is a work-in-progress. The spiritual practice of you challenges us to become all we are meant to be as God's beloved sons and daughters. We are, after all, co-creators of the Great Work of the universe. By attuning ourselves to what in different traditions has been called the image of God, the everlasting soul, or the higher self, we are able to fulfill our mission in life.* As we remember the names we carry, we are practing You in two ways. We are honoring our own You, not as a self-contained island unto itself, but as a composite made up of many without whom we could not become ourselves. We are saying "yes" to our existential multiplicity. And we are simultaneously honoring their You as different from our own. We are saying "yes" to differences. Deep down we are also honoring the You in whom, so process theologians propose, the universe of yous unfolds. God is the You in whose life all the other yous live and move and have their being. God is grateful for the other yous, otherwise God would be so alone and maybe even non-existent. Did God not say, on the seventh day, that the world of hills and rivers, stars and galaaxies, people and other animals, was all very good. Isn't God, too, glad for the existence of multiple yous who help make God "God." Might God, too, write thank you notes? -- Jay McDaniel |

* https://www.spiritualityandpractice.com/practices/alphabet/view/38/you