- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

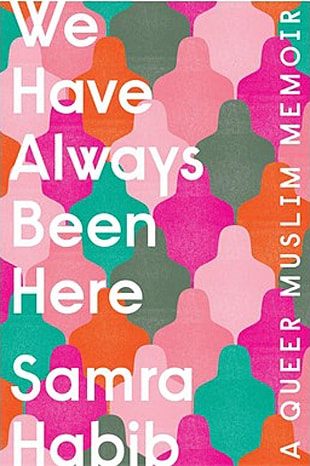

We Have Always Been Here

A Queer Muslim Memoir

By Samra Habib

Powerful memoir of a queer Muslim woman

who “dares to imagine a beautiful life.”

Book Review by Jon M. Sweeney. Reposted from Spirituality and Practice

Samra Habib was born into a traditional Muslim family in Lahore, Pakistan. As a child she remembers, “I’d only ever been surrounded by women who didn’t have the blueprint for claiming their lives.” Her own mother had been assigned a new name, without consultation, by her father. “He had decided that Yasmin would be a more suitable and elegant name for his wife than Frida. It was one of the first signs that her identity was disposable.”

“Allah hates the loud laughter of women!” her father bellowed at her once, when she was a child playing.

This is Samra’s story of claiming her life and identity as her own. She builds it, beginning when her family arrives in Canada as refugees. After many travails and discoveries, including an arranged marriage, then a divorce, she comes out as queer and begins to build a new life. She is still a young woman, and by the book’s conclusion there is the sense that she’s very much still in the process of building.

We Have Always Been Here is also a memoir about religious difference — not only of Habib’s being Muslim in Canada, where Muslims make up only three percent of the population — but of being part of a small sect within a dominant religious tradition. Habib’s family was Ahmadi Muslim in Pakistan. The Ahmadiyya Movement takes its name from their founder, a Muslim reformer, who in the late nineteenth century proclaimed himself the messiah and preached non-violence and tolerance of other faiths as a way of returning to the original intentions of the Prophet Muhammad. Ahmadis are routinely assaulted in Pakistan. “Stories of Ahmadi businesses being set ablaze and Ahmadi mosques being besieged by gunmen are sadly common,” Habib writes. “A cousin of mine narrowly avoided getting killed when Sunni extremists barged into a mosque during Friday prayer and opened fire.” Her family immigrated to Canada on the grounds of religious persecution.

By chapter 10, she’s joining Unity Mosque, a prayer space created for queer Muslims. And by chapter 12, she’s delivering a keynote conference talk in North Carolina entitled “Spirituality as a Radical Tool.”

We think you’ll find this book inspiring for your own path.

- Jon M. Sweeney

Excerpt

“I became a little more adventurous with my look. I started going to a salon downtown that resembled a spaceship, where you were given an asymmetrical mullet no matter what you asked for and Depeche Mode and New Order blasted over the speakers. Inspired by the feeling of ownership over my body, I got my first tattoo, of the Japanese word for beauty (my fascination with the country and culture had only grown since ESL class with Ms. Nakamura). I felt a flicker of buried guilt as the tool pierced my skin, knowing that tattoos are forbidden in Islam. But by the time it healed, I was already thinking about what I’d get for my second.

“I’d started using LiveJournal and connected with a group of young feminist women of colour who were a bit older than me and had started their careers, mostly in media. Meeting people online was one of the few ways I could form connections with people I had something in common with. Alienated from my family and the mosque community, I’d become intensely aware of the lack of people of colour in my life and was trying to remedy that. I was certain that by doing so I would find comfort and finally be understood in my entirety.

“That summer, after weeks of exchanging ideas and messages online, some of the women made plans to meet for a picnic in a park. I showed up late from an afternoon shift at the Body Shop and added the container of mushroom pasta with congealed rose sauce I’d picked up from the grocery store to their array of gluten-free and vegan offerings. I quickly learned that although the group was strictly for women of colour, I was the only one who was not born in Canada. Many of them had the emotional and financial support of their parents, who had well-paying jobs and had never had to struggle with a language barrier.

“ 'What are some of the biggest challenges you’ve had to confront as a person of colour?' the ringleader, a brown girl with a Sleater-Kinney T-shirt, asked the group. One by one, the others in the circle shared how instances of racism and sexism had prevented them from getting the same opportunities in their careers as their peers. I straightened my back, which ached from being on my feet all day at the shop. The privilege of being second or even third generation wasn’t lost on me.

“By the time it was my turn to speak, I could feel myself shaking; I wondered if my voice would betray me. But I couldn’t bring myself to sugar-coat it. 'I guess the biggest challenges I’ve faced are escaping my arranged marriage and dealing with the fear that I’ll have to go on welfare like my parents,' I said, pulling blades of grass from the wet ground, not quite able to look any of the girls in the eye. Everyone was quiet, as if unsure what to say. Weighed down by their silence and inability to connect, I felt even more isolated.”

“I’d started using LiveJournal and connected with a group of young feminist women of colour who were a bit older than me and had started their careers, mostly in media. Meeting people online was one of the few ways I could form connections with people I had something in common with. Alienated from my family and the mosque community, I’d become intensely aware of the lack of people of colour in my life and was trying to remedy that. I was certain that by doing so I would find comfort and finally be understood in my entirety.

“That summer, after weeks of exchanging ideas and messages online, some of the women made plans to meet for a picnic in a park. I showed up late from an afternoon shift at the Body Shop and added the container of mushroom pasta with congealed rose sauce I’d picked up from the grocery store to their array of gluten-free and vegan offerings. I quickly learned that although the group was strictly for women of colour, I was the only one who was not born in Canada. Many of them had the emotional and financial support of their parents, who had well-paying jobs and had never had to struggle with a language barrier.

“ 'What are some of the biggest challenges you’ve had to confront as a person of colour?' the ringleader, a brown girl with a Sleater-Kinney T-shirt, asked the group. One by one, the others in the circle shared how instances of racism and sexism had prevented them from getting the same opportunities in their careers as their peers. I straightened my back, which ached from being on my feet all day at the shop. The privilege of being second or even third generation wasn’t lost on me.

“By the time it was my turn to speak, I could feel myself shaking; I wondered if my voice would betray me. But I couldn’t bring myself to sugar-coat it. 'I guess the biggest challenges I’ve faced are escaping my arranged marriage and dealing with the fear that I’ll have to go on welfare like my parents,' I said, pulling blades of grass from the wet ground, not quite able to look any of the girls in the eye. Everyone was quiet, as if unsure what to say. Weighed down by their silence and inability to connect, I felt even more isolated.”

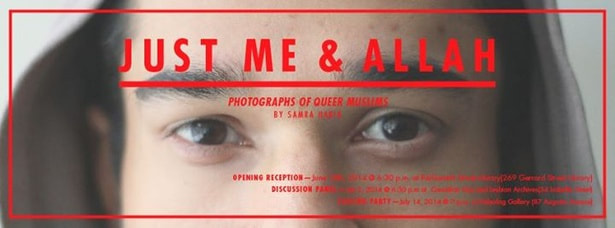

Samra Habib: Videos

|

|

|

Atlanta Unity Mosque

About Us

"El-Tawhid Juma Circle (eTJC) Unity Mosques operate under the concept of radical Tawhid. The eTJC Unity Mosque family of congregations is founded on the certainty that all human beings, without exception, are equal to one another socially and ritually and in potential Divine agency. All are welcome at eTJC Unity Mosques spaces for prayer, community, reflection, and discussion which affirm and include all. ETJC Unity Mosques are places of healing for everyone ETJC Unity Mosques are safe spaces for everyone to worship, commune, and just be. We celebrate pluralism and diversity enshrined in 49:13 of the Quran.

ETJC Unity Mosques extend an intentional welcome to people of all races, classes, abilities, health (including HIV) status, sexual orientations, gender identities, sex, ages, family and relationship statuses, and religions. ETJC Unity Mosque's beliefs and practises are based on the understanding that all persons are equal agents of Allah in all aspects of ritual practice. Everyone is welcome, even encouraged to take a turn in each aspect of Juma services, including but not limited to making the call to prayer, giving the sermon, and leading the ritual Friday prayer. We stand for radical tawhid. Absolute Oneness. Absolute Equality, like the teeth of a comb, shoulder to shoulder against injustice and tyranny, including tyranny from the pulpit. That is our Islam. Nothing else."

"El-Tawhid Juma Circle (eTJC) Unity Mosques operate under the concept of radical Tawhid. The eTJC Unity Mosque family of congregations is founded on the certainty that all human beings, without exception, are equal to one another socially and ritually and in potential Divine agency. All are welcome at eTJC Unity Mosques spaces for prayer, community, reflection, and discussion which affirm and include all. ETJC Unity Mosques are places of healing for everyone ETJC Unity Mosques are safe spaces for everyone to worship, commune, and just be. We celebrate pluralism and diversity enshrined in 49:13 of the Quran.

ETJC Unity Mosques extend an intentional welcome to people of all races, classes, abilities, health (including HIV) status, sexual orientations, gender identities, sex, ages, family and relationship statuses, and religions. ETJC Unity Mosque's beliefs and practises are based on the understanding that all persons are equal agents of Allah in all aspects of ritual practice. Everyone is welcome, even encouraged to take a turn in each aspect of Juma services, including but not limited to making the call to prayer, giving the sermon, and leading the ritual Friday prayer. We stand for radical tawhid. Absolute Oneness. Absolute Equality, like the teeth of a comb, shoulder to shoulder against injustice and tyranny, including tyranny from the pulpit. That is our Islam. Nothing else."