- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

We Shall Overcome: Joan Baez

by Patricia Campbell Carlson

reposted from Spirituality and Practice

Through benefit concerts and civil disobedience over the course of decades, renowned folksinger and songwriter Joan Baez has brought her influence to bear on issues of free speech, opposition to the Vietnam War and other military engagements of the United States, LGBT rights, desegregated schools, rights of farm workers, abolition of the death penalty, and the nuclear freeze movement. She persists in practicing civil disobedience and has faced legal challenges for following her conscience.

In 1941, Baez was born in New York City to a Methodist family. When she was still a young child, they became Quakers, kindling her ardent dedication to pacifism and social causes. Her Mexican heritage made her the brunt of discrimination when she was growing up, helping her understand prejudice from the inside out. She got involved in nonviolent social action beginning in her high school years, after hearing Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. speak. She marched on the front lines of the Civil Rights Movement in Alabama and Mississippi.

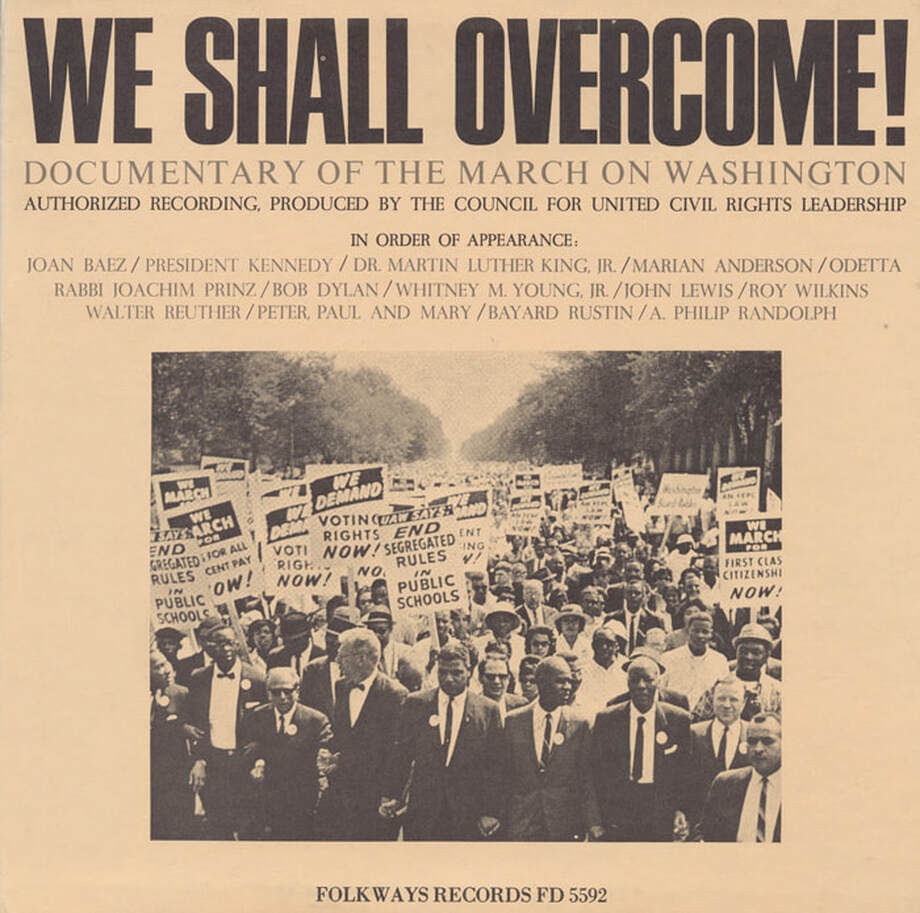

As a singer, Baez first became known for the penetrating clarity of her voice and message while performing at the 1959 Newport Folk Festival. She went on during the 1960s to transform traditional ballads into the rock vernacular. In 1963, she unselfconsciously introduced then little-known Bob Dylan to the world. She was emulated by world-class musicians like Judy Collins, Joni Mitchell, and Bonnie Raitt.

In 1979, Baez founded Humanitas International Human Rights Committee; she served as its leader for 13 years. She has received seven grammy nominations and, at the 2007 Grammy Awards, was given a Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. In 2011, Amnesty International bestowed on her the inaugural Joan Baez Award for Outstanding Inspirational Service in the Global Fight for Human Rights. You can learn more about her music and her extensive accomplishments at the Joan Baez website.

|

|

|

Mutual Overcoming

We shall overcome with God's loving energy

and God shall overcome with ours

I love the song We Shall Overcome. If given the chance to sing it with others or just listen to it, I’m on board. Sometimes I sing it alone, by myself, just for comfort’s sake. I like Mahalia Jackson’s and Joan Baez’s versions the most. Both are offered on this page.

I know the song has a rich history that precedes the Civil Rights movement in the United States and that it was a signature song in the movement as well. Pete Seeger tells the story below. I feel so small compared to the heroes and heroines of that movement. That doesn't matter.

Still, I sing it, too. Today, as I hear it, I think of so many things I’d like to help overcome - greed, hatred, violence, discrimination, economic inequities, the abuse of animals, and the abuse of the earth, for example. And I think of the habits of thought that give rise to these problems: mechanistic thinking where all things are reduced to “objects” in the marketplace, predatory capitalism and a love of money, the assumptions of white supremacy, for example. All are worth overcoming.

When I imagine what things would be like if they were overcome, I think of beloved communities and ecological civilizations. Those are the kinds of societies I'd to help us overcome into. They are the lights at the end of the tunnel. They are what the song is about. The song is a song of hope.

Occasionally, when I am in the presence of conservative Christians who speak of God as “in control,” I ask myself why, if they really believe this, why don’t they just let God do the overcoming. Or trust that even the problems are part of God’s control and not worth worrying about.

But I know that they don’t really believe God is in this much control. They act as if their actions count, as if God needs them as partners to help in the overcoming. They act as if the overcoming is a mutual process, in which their actions are essential to God.

Along with John Cobb below, I think it best to take the “as if” very seriously. The truth is: God needs us for the will of God to be done on earth as it is in heaven. At least this is the way it seems from an open and relational (process) perspective. We open and relational (process) thinkers believe that God needs us just as we need God.

I don’t really imagine a time on earth when everything will be fully overcome. I don’t imagine a time when beloved communities and ecological civilizations will be fully embodied and here to stay. I’ll wait for heaven on that one.

But I do imagine times when the two ideals of beloved community and ecological civilization can be approximated. I do imagine what some call “a new possible” here on Earth. It is our hands, with God’s help, that will do the overcoming.

Back, then, to the song. For me as a process theologian, We Shall Overcome is an invitation to hope and to roll up our sleeves and get to work, trusting that we’re not alone. We have each other; we have the energies of nature; and even more deeply we have the energy of love pulling us and enlivening us. This love energy is God. Love energy is not just an idea or an object of belief. It is, as Gandhi and King recognized, a force at work in the world: a force that needs our hands to help it be actualized.

I wonder if, deep down, God isn’t singing We Shall Overcome, too. In an essay below, John Cobb says that our hands are God’s hands. Perhaps our lips, or least Mahalia’s and Joan's lips, are God’s lips, too. Maybe even Pete Seeger's lips.

But we sing with them in hearing them with sympathetic hearts. Their lips are our lips, too. The interconnectedness of things, the way in which our feelings flow into others and theirs into ours, sometimes in such loving ways, is part of what God seeks and loves and needs. Our feelings of love and hope flow into God's life, enriching God's own living subjectivity, says the philosopher Whitehead; and that love, as enriched by our own, then flows back into the world in a kind of divine recycling.

Truth be told, in the very singing of We Shall Overcome, there's a little overcoming in us and in God. This overcoming, in singing itself, is love energy, too. It is a seed for more love in the world. Bottom line? Keep singing.

- Jay McDaniel, January 18, 2022

I know the song has a rich history that precedes the Civil Rights movement in the United States and that it was a signature song in the movement as well. Pete Seeger tells the story below. I feel so small compared to the heroes and heroines of that movement. That doesn't matter.

Still, I sing it, too. Today, as I hear it, I think of so many things I’d like to help overcome - greed, hatred, violence, discrimination, economic inequities, the abuse of animals, and the abuse of the earth, for example. And I think of the habits of thought that give rise to these problems: mechanistic thinking where all things are reduced to “objects” in the marketplace, predatory capitalism and a love of money, the assumptions of white supremacy, for example. All are worth overcoming.

When I imagine what things would be like if they were overcome, I think of beloved communities and ecological civilizations. Those are the kinds of societies I'd to help us overcome into. They are the lights at the end of the tunnel. They are what the song is about. The song is a song of hope.

Occasionally, when I am in the presence of conservative Christians who speak of God as “in control,” I ask myself why, if they really believe this, why don’t they just let God do the overcoming. Or trust that even the problems are part of God’s control and not worth worrying about.

But I know that they don’t really believe God is in this much control. They act as if their actions count, as if God needs them as partners to help in the overcoming. They act as if the overcoming is a mutual process, in which their actions are essential to God.

Along with John Cobb below, I think it best to take the “as if” very seriously. The truth is: God needs us for the will of God to be done on earth as it is in heaven. At least this is the way it seems from an open and relational (process) perspective. We open and relational (process) thinkers believe that God needs us just as we need God.

I don’t really imagine a time on earth when everything will be fully overcome. I don’t imagine a time when beloved communities and ecological civilizations will be fully embodied and here to stay. I’ll wait for heaven on that one.

But I do imagine times when the two ideals of beloved community and ecological civilization can be approximated. I do imagine what some call “a new possible” here on Earth. It is our hands, with God’s help, that will do the overcoming.

Back, then, to the song. For me as a process theologian, We Shall Overcome is an invitation to hope and to roll up our sleeves and get to work, trusting that we’re not alone. We have each other; we have the energies of nature; and even more deeply we have the energy of love pulling us and enlivening us. This love energy is God. Love energy is not just an idea or an object of belief. It is, as Gandhi and King recognized, a force at work in the world: a force that needs our hands to help it be actualized.

I wonder if, deep down, God isn’t singing We Shall Overcome, too. In an essay below, John Cobb says that our hands are God’s hands. Perhaps our lips, or least Mahalia’s and Joan's lips, are God’s lips, too. Maybe even Pete Seeger's lips.

But we sing with them in hearing them with sympathetic hearts. Their lips are our lips, too. The interconnectedness of things, the way in which our feelings flow into others and theirs into ours, sometimes in such loving ways, is part of what God seeks and loves and needs. Our feelings of love and hope flow into God's life, enriching God's own living subjectivity, says the philosopher Whitehead; and that love, as enriched by our own, then flows back into the world in a kind of divine recycling.

Truth be told, in the very singing of We Shall Overcome, there's a little overcoming in us and in God. This overcoming, in singing itself, is love energy, too. It is a seed for more love in the world. Bottom line? Keep singing.

- Jay McDaniel, January 18, 2022

God has no Hands

John B. Cobb, Jr.

from Partnering with God: Exploring Collaboration in Open and Relational Theology,

edited by Rambob, Stedman, and Oord, SacraSage Press, 2021

Perhaps God’s greatest gift to you is to call you to be a responsible partner.

When I was a boy growing up in the Methodist Youth Fellowship, we used to sing a song that began with “God has no hands but our hands.” We did not think that diminished God. But we felt drawn to make our hands available for God’s work. We were partners with God!

The song went on to say: “God has no feet but our feet.” God is lacking not only in hands but in a body. There are many things that can only be done by bodies.

Jesus told a parable about “a good Samaritan” (Luke 10:25-30). The story is about a man who is robbed and beaten and left helpless by the side of the road. Jesus was a Jew. So, he said that Jewish leaders passed by ignoring the man’s needs. They were too busy doing the work of the synagogue or temple to help the man. The Jews were contemptuous of Samaritans; so Jesus said that a Samaritan stopped to help and lavishly assisted the man who was helpless. Of course, his point was to remind Jews that just being a Jew was not a great achievement in God’s eyes. What was important was to act lovingly to those in need. A loving Samaritan was a far better servant of God than an unloving Jew.

The point of the parable was not about what we should expect God to do. There is no hint that God might intervene and miraculously help the wounded man. It is not a story about how people prayed for him and that did the job. Jesus and his hearers took for granted that if the man was going to receive help, it would be from another human being. The question was whether anyone would help and, if so, who.

It is not only for taking physical actions that God needs people. God needs us in the work of sharing the good news. In the tenth chapter of Romans, Paul writes about the need for people to hear the gospel in order to believe. Think about verses 13 and 14 and the first part of 15:

For “everyone who calls upon the name of the Lord will be saved.” But how are men to call upon him in whom they have not believed? And how are they to believe in him of whom they have never heard? And how are they to hear without a preacher? And how can men preach unless they are sent?

One could hardly be clearer that God needs partners in the process of converting people to the Christian faith. All churches that I know act as if they believe this. They organize and raise money so that more people can hear the gospel. Almost everyone acts as if they understood that we have a role, that God needs partners.

Sadly, some have persuaded themselves that in fact God does it all regardless of what we do. This strange idea is based on a word that appears rarely in the Bible: “predestine.” A whole system of thought has been built around this word. And although even those who adhere to it often act as if God needs humans to spread his word, that system of thought often gets in the way. Indeed, it becomes integrated into an entire system of thought that affirms that God determines everything. That is certainly not the system of thought expressed in this or other passages in Paul’s writings.

Some of us think that Paul remains the greatest Christian theologian. We think that Paul thought of our partnering with God rather than of God predestining us and everything. Even the few passages where Paul uses the word “predestine” don’t support the system that has been built on a misreading of it. Let’s look at one verse often used to support the idea that, from the beginning of time, God had chosen who would believe.

The verse is Romans 8:29, “for those whom he foreknew he also predestined to conform to the image of his Son.” Clearly it is what God foreknows that enables God to predestine. Of course, God foreknows a lot more than we do, and so he can predestine a lot more than we can. But the Bible does not teach that God foreknows just how people will decide. In the biblical accounts, God is often disappointed and sometimes changes plans.

But even I can say that I know some people who I “foreknow” I can trust no matter what. Based on that knowledge, I can plan some parts of the future. If God knows in advance that some people are so oriented that when they hear the good news they will respond enthusiastically, then God can plan in advance “to confirm them in the image of Jesus.” That makes good sense. It certainly does not justify supposing that God makes all the decisions without the need for human partners. It means, instead, that God can be confident that some people will make good partners and plan accordingly.

Thus far I have expressed my strong conviction as a Christian who takes the New Testament seriously. I am convinced that Jesus and Paul and other early followers of Jesus felt they had an important role to play as partners with God. That is true today when we straighten up our room, or join others in a meal, or protect sources of fresh water, or show friendship to someone who is lonely, or work to save the world from self-destruction. In other words, it applies to everything. We have some responsibility in every act.

This leaves open the question of what God is doing. What is God’s role as partner? Some people think God created the world, set up the governing laws, and then left everything to us. I don’t like that image of partnership, and I don’t find it in the Bible. Especially in the New Testament, we read of God’s gracious presence in our lives. Just before the previous quote from Paul is another one: “We know that in everything God works for good.”

That does not say that God controls everything or that God is the only influence on what happens. It says that God plays a role in everything, and it assures us that God’s role is always to bring about what good is possible. God contributes to every event in our lives. So do we. God works for good.

We can partner with God. But we can also resist God or oppose God. Most of us have some experience of working with God. That gives us a sense of living a meaningful life. We also have the experience of falling short of the full possibilities of partnership, what the New Testament calls “missing the mark.” Sometimes that is translated as “sin.” Yes, we are all “sinners.” To the extent that we partner with God, new possibilities for partnering emerge. To the extent that we fall short, what is possible is reduced.

Much else contributes to every experience besides God and our own decisions. Some of us think that everything that has ever happened has some effect on what happens now. Of course, minor events long ago have trivial effects, while an accident the day before may be the most important factor in what is happening now.

Recognizing that much is determined by the past, and that our own decisions play a decisive role, what does God contribute as our partner? That’s a large and important topic. I’ll just make a few quick stabs.

God works in every cell in our bodies, giving life, and growth, and healing. We can partner with God by taking actions supportive of the life and growth and healing of our bodies. Medical professionals cannot take the place of what we call “natural” forces in our bodies. But they can remove obstacles to their effectiveness.

God calls us in each moment to be a good partner, that is, to decide for that which is best. Sometimes that call expresses a wisdom beyond our knowledge. We need to listen to discern the voice of God amid all the competing voices.

God enables us to act as we are called to act. If we trust God, we can do things that our fears would keep us from even trying. New horizons open before us.

We can experience God’s compassion. That is, God feels our feelings with us. This is the one relationship in which we are fully known, fully understood, fully accepted, and totally loved.

Because we know God loves us even when we resist that love and rebel against it, we can become free from preoccupation with ourselves and truly love others. The center of Jewish teaching is that we love God and neighbor. The experience of being totally accepted and loved makes it possible for us to love God and neighbor.

Jesus called for more. God loves not only us but also those whom we fear and oppose, “our enemies.” Because of God’s strengthening us, we can love our enemies too. That is the greatest and most redemptive possibility

John B. Cobb, Jr. is a retired professor from the Claremont School of Theology. He has promoted “process theology” and believes that good theology challenges all the institutions of society to give up destructive assumptions and reconstruct themselves around love. He lives in Pilgrim Place, a retirement community in Claremont, California.

When I was a boy growing up in the Methodist Youth Fellowship, we used to sing a song that began with “God has no hands but our hands.” We did not think that diminished God. But we felt drawn to make our hands available for God’s work. We were partners with God!

The song went on to say: “God has no feet but our feet.” God is lacking not only in hands but in a body. There are many things that can only be done by bodies.

Jesus told a parable about “a good Samaritan” (Luke 10:25-30). The story is about a man who is robbed and beaten and left helpless by the side of the road. Jesus was a Jew. So, he said that Jewish leaders passed by ignoring the man’s needs. They were too busy doing the work of the synagogue or temple to help the man. The Jews were contemptuous of Samaritans; so Jesus said that a Samaritan stopped to help and lavishly assisted the man who was helpless. Of course, his point was to remind Jews that just being a Jew was not a great achievement in God’s eyes. What was important was to act lovingly to those in need. A loving Samaritan was a far better servant of God than an unloving Jew.

The point of the parable was not about what we should expect God to do. There is no hint that God might intervene and miraculously help the wounded man. It is not a story about how people prayed for him and that did the job. Jesus and his hearers took for granted that if the man was going to receive help, it would be from another human being. The question was whether anyone would help and, if so, who.

It is not only for taking physical actions that God needs people. God needs us in the work of sharing the good news. In the tenth chapter of Romans, Paul writes about the need for people to hear the gospel in order to believe. Think about verses 13 and 14 and the first part of 15:

For “everyone who calls upon the name of the Lord will be saved.” But how are men to call upon him in whom they have not believed? And how are they to believe in him of whom they have never heard? And how are they to hear without a preacher? And how can men preach unless they are sent?

One could hardly be clearer that God needs partners in the process of converting people to the Christian faith. All churches that I know act as if they believe this. They organize and raise money so that more people can hear the gospel. Almost everyone acts as if they understood that we have a role, that God needs partners.

Sadly, some have persuaded themselves that in fact God does it all regardless of what we do. This strange idea is based on a word that appears rarely in the Bible: “predestine.” A whole system of thought has been built around this word. And although even those who adhere to it often act as if God needs humans to spread his word, that system of thought often gets in the way. Indeed, it becomes integrated into an entire system of thought that affirms that God determines everything. That is certainly not the system of thought expressed in this or other passages in Paul’s writings.

Some of us think that Paul remains the greatest Christian theologian. We think that Paul thought of our partnering with God rather than of God predestining us and everything. Even the few passages where Paul uses the word “predestine” don’t support the system that has been built on a misreading of it. Let’s look at one verse often used to support the idea that, from the beginning of time, God had chosen who would believe.

The verse is Romans 8:29, “for those whom he foreknew he also predestined to conform to the image of his Son.” Clearly it is what God foreknows that enables God to predestine. Of course, God foreknows a lot more than we do, and so he can predestine a lot more than we can. But the Bible does not teach that God foreknows just how people will decide. In the biblical accounts, God is often disappointed and sometimes changes plans.

But even I can say that I know some people who I “foreknow” I can trust no matter what. Based on that knowledge, I can plan some parts of the future. If God knows in advance that some people are so oriented that when they hear the good news they will respond enthusiastically, then God can plan in advance “to confirm them in the image of Jesus.” That makes good sense. It certainly does not justify supposing that God makes all the decisions without the need for human partners. It means, instead, that God can be confident that some people will make good partners and plan accordingly.

Thus far I have expressed my strong conviction as a Christian who takes the New Testament seriously. I am convinced that Jesus and Paul and other early followers of Jesus felt they had an important role to play as partners with God. That is true today when we straighten up our room, or join others in a meal, or protect sources of fresh water, or show friendship to someone who is lonely, or work to save the world from self-destruction. In other words, it applies to everything. We have some responsibility in every act.

This leaves open the question of what God is doing. What is God’s role as partner? Some people think God created the world, set up the governing laws, and then left everything to us. I don’t like that image of partnership, and I don’t find it in the Bible. Especially in the New Testament, we read of God’s gracious presence in our lives. Just before the previous quote from Paul is another one: “We know that in everything God works for good.”

That does not say that God controls everything or that God is the only influence on what happens. It says that God plays a role in everything, and it assures us that God’s role is always to bring about what good is possible. God contributes to every event in our lives. So do we. God works for good.

We can partner with God. But we can also resist God or oppose God. Most of us have some experience of working with God. That gives us a sense of living a meaningful life. We also have the experience of falling short of the full possibilities of partnership, what the New Testament calls “missing the mark.” Sometimes that is translated as “sin.” Yes, we are all “sinners.” To the extent that we partner with God, new possibilities for partnering emerge. To the extent that we fall short, what is possible is reduced.

Much else contributes to every experience besides God and our own decisions. Some of us think that everything that has ever happened has some effect on what happens now. Of course, minor events long ago have trivial effects, while an accident the day before may be the most important factor in what is happening now.

Recognizing that much is determined by the past, and that our own decisions play a decisive role, what does God contribute as our partner? That’s a large and important topic. I’ll just make a few quick stabs.

God works in every cell in our bodies, giving life, and growth, and healing. We can partner with God by taking actions supportive of the life and growth and healing of our bodies. Medical professionals cannot take the place of what we call “natural” forces in our bodies. But they can remove obstacles to their effectiveness.

God calls us in each moment to be a good partner, that is, to decide for that which is best. Sometimes that call expresses a wisdom beyond our knowledge. We need to listen to discern the voice of God amid all the competing voices.

God enables us to act as we are called to act. If we trust God, we can do things that our fears would keep us from even trying. New horizons open before us.

We can experience God’s compassion. That is, God feels our feelings with us. This is the one relationship in which we are fully known, fully understood, fully accepted, and totally loved.

Because we know God loves us even when we resist that love and rebel against it, we can become free from preoccupation with ourselves and truly love others. The center of Jewish teaching is that we love God and neighbor. The experience of being totally accepted and loved makes it possible for us to love God and neighbor.

Jesus called for more. God loves not only us but also those whom we fear and oppose, “our enemies.” Because of God’s strengthening us, we can love our enemies too. That is the greatest and most redemptive possibility

John B. Cobb, Jr. is a retired professor from the Claremont School of Theology. He has promoted “process theology” and believes that good theology challenges all the institutions of society to give up destructive assumptions and reconstruct themselves around love. He lives in Pilgrim Place, a retirement community in Claremont, California.

We Shall Overcome: Pete Seeger

Like nearly all folk songs, “We Shall Overcome” has a convoluted, obscure history that traces back to no single source. The Library of Congress locates the song’s origins in “African American hymns from the early 20th century” and an article on About.com dates the melody to an antebellum song called “No More Auction Block for Me” and the lyrics to a turn-of-the-century hymn written by the Reverend Charles Tindley of Philadelphia. The original lyric was one of personal salvation—“I’ll Overcome Someday”—but at least by 1945, when the song was taken up by striking tobacco workers in Charleston, S.C., it was transmuted into a statement of solidarity as “We Will Overcome.” Needless to say, in its final form, “We Shall Overcome” became the unofficial anthem of the labor and Civil Rights movements and eventually came to be sung “in North Korea, in Beirut, Tiananmen Square and in South Africa’s Soweto Township.”

Pete Seeger—who passed away at the age of 94—has long been credited with the dissemination of “We Shall Overcome,” but he was always quick to cite his sources. Seeger heard the song in 1947 from folklorist Zilphia Horton, music director at Tennessee’s Highlander Folk Center who, Seeger said, “had a beautiful alto voice and sang it with no rhythm.” As he told NPR recently, his touches were also those of other singers:

I gave it kind of ump-chinka, ump-chinka, ump-chinka, ump-chinka, ump-chinka, ump. It was medium slow as I sang it, but the banjo kept a steady rhythm going. I remember teaching it to a gang in Carnegie Hall that year, and the following year I put it in a little music magazine called People’s Songs. Over the years, I remember singing it two different ways. I’m usually credited with changing [‘Will’] to ‘Shall,’ but there was a black woman who taught at Highlander Center, a wonderful person named Septima Clark. And she always liked shall, too, I’m told.

According to Seeger in the interview above--conducted by Josh Baron before a 2010 performance—the person most responsible for “making it the number one song back in those days” was the Music Director of the Highlander Folk Center, Guy Carawan, who “sent messages to the civil rights movement all through the South from Texas to Florida to Maryland.” Carawan “introduced this song with a new rhythm that I had never heard before.” Seeger goes on to describe the rhythm in detail, then says “it was the hit song of the weekend in February 1960…. It was not a song, it was the song all across the South. I’ve found out since then that the song started off as a union song in the 19th century.”

In this particular interview, Seeger takes full credit for changing the “will” to “shall.” Although it was “the only record [he] made which sold,” he didn’t seek to cash in on his changes (Seeger shared the copyright with Zilphia Horton, Carawan, and Frank Hamilton). As you can easily see from the numerous eulogies and tributes popping up all over (or a quick scan of the “Pete Seeger Appreciation Page”), Seeger deserves to be remembered for much more than his sixties folk singing, but he perhaps did more than anyone to make “We Shall Overcome” a song sung by a nation. And as he tells it, it was song he hoped would resonate worldwide:

I was singing for some young Lutheran church people in Sundance, Idaho, and there were some older people who were mistrustful of my lefty politics. They said: ‘Who are you intending to overcome?’ I said: ‘Well, in Selma, Alabama they’re probably thinking of Chief Pritchett.; they will overcome. And I am sure Dr. King is thinking of the system of segregation across the whole country, not just the South. For me, it means the entire world. We’ll overcome our tendencies to solve our problems with killing and learn to work together to bring this world together.

from Open Culture: https://openculture.com/2014/01/pete-seeger-tells-the-story-behind-we-shall-overcome.html

Pete Seeger—who passed away at the age of 94—has long been credited with the dissemination of “We Shall Overcome,” but he was always quick to cite his sources. Seeger heard the song in 1947 from folklorist Zilphia Horton, music director at Tennessee’s Highlander Folk Center who, Seeger said, “had a beautiful alto voice and sang it with no rhythm.” As he told NPR recently, his touches were also those of other singers:

I gave it kind of ump-chinka, ump-chinka, ump-chinka, ump-chinka, ump-chinka, ump. It was medium slow as I sang it, but the banjo kept a steady rhythm going. I remember teaching it to a gang in Carnegie Hall that year, and the following year I put it in a little music magazine called People’s Songs. Over the years, I remember singing it two different ways. I’m usually credited with changing [‘Will’] to ‘Shall,’ but there was a black woman who taught at Highlander Center, a wonderful person named Septima Clark. And she always liked shall, too, I’m told.

According to Seeger in the interview above--conducted by Josh Baron before a 2010 performance—the person most responsible for “making it the number one song back in those days” was the Music Director of the Highlander Folk Center, Guy Carawan, who “sent messages to the civil rights movement all through the South from Texas to Florida to Maryland.” Carawan “introduced this song with a new rhythm that I had never heard before.” Seeger goes on to describe the rhythm in detail, then says “it was the hit song of the weekend in February 1960…. It was not a song, it was the song all across the South. I’ve found out since then that the song started off as a union song in the 19th century.”

In this particular interview, Seeger takes full credit for changing the “will” to “shall.” Although it was “the only record [he] made which sold,” he didn’t seek to cash in on his changes (Seeger shared the copyright with Zilphia Horton, Carawan, and Frank Hamilton). As you can easily see from the numerous eulogies and tributes popping up all over (or a quick scan of the “Pete Seeger Appreciation Page”), Seeger deserves to be remembered for much more than his sixties folk singing, but he perhaps did more than anyone to make “We Shall Overcome” a song sung by a nation. And as he tells it, it was song he hoped would resonate worldwide:

I was singing for some young Lutheran church people in Sundance, Idaho, and there were some older people who were mistrustful of my lefty politics. They said: ‘Who are you intending to overcome?’ I said: ‘Well, in Selma, Alabama they’re probably thinking of Chief Pritchett.; they will overcome. And I am sure Dr. King is thinking of the system of segregation across the whole country, not just the South. For me, it means the entire world. We’ll overcome our tendencies to solve our problems with killing and learn to work together to bring this world together.

from Open Culture: https://openculture.com/2014/01/pete-seeger-tells-the-story-behind-we-shall-overcome.html