- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

The Beauty of Imperfection

Patricia Adams Farmer

|

|

The Elusive Quest for Perfection

Typos are the bane of my existence. Maybe I’m just a singularly neurotic writer, but I doubt that I’m alone in this. Trying to rid a manuscript of typos is like guerrilla warfare in the jungle. The brutality never ends—never. Just when you start to feel safe, the misplaced comma, the missing quotation mark, the glaring absence of a preposition, or worst of all, the misspelled word ambush you. Typos are sinister; they taunt and mock and jeer for the sport of it—it’s what they do. It’s their raison d’etre. That’s why writers have someone else proof their work, but even then, some particularly devious typos sneak by the editor into publication, like stowaways on a ship waiting with evil relish to emerge, brazenly, just after the boat sails. Would I have it any other way? Would it be better to half-heartedly glance over my work and pronounce it “good enough”? Of course not. I think it’s good to struggle with something you love—to do some serious suffering, even while knowing that perfection is elusive. Striving for perfection has its moments—think of great pianists or Olympic athletes—and it can even save lives. I fervently hope that people who dismantle bombs are perfectionists—obsessively so—as well as doctors who perform delicate surgery. And heaven help us if our dentists declare a botched root canal, “good enough.” We need to strive for excellence, of course we do—but we need to be wary of perfectionism, for as we climb that steep mountain on our way to our ideal, we might just lose our footing and go crashing down in a heap. Perfectionism has a dark and dangerous side. Perfectionism: The Dark Side Perfectionism, a fairly innocuous word, can in fact make us miserable and neurotic and play heinous tricks on our psyche. It can make us sick. Perfectionism is a dangerous game and, if not watched carefully, can turn tragic. For example, women are inundated from an early age with magazine ads showing gaunt, curve-less bodies as if they are the “ideal.” Anything outside the perimeters of that ultra-thin, half-emaciated ideal is to be stamped INFERIOR, and thus most of us go around feeling quite dissatisfied with—or even ashamed of—our bodies. Thanks to the Tyranny of Thin, eating disorders continue to take their toll on—even kill—bright, talented young women. Remember Karen Carpenter. Listen to her voice and weep for all that was lost. She died of complications from anorexia nervosa at age 32, a complex illness, but one in which a driving force is perfectionism-gone-mad. And for the anorexic, perfectionism does not stop with body image, but infiltrates the whole personality. One's entire life-orientation becomes hostage to elusive ideals of perfection. On the socio-political level, radical idealists strive, sometimes violently, for their version of the perfect political system or perfect religion. Worse still—maybe worst of all—are those who believe in an ideal skin color or “race.” History breaks our hearts with its testimony of such madness. Granted, these are extreme examples, but even in our everyday lives we are besieged by this vague, unspoken notion that there are “ideals” out there that we have to live up to, or else we are simply inferior beings that might as well be wiped off the page like dangling modifiers. We feel we need the perfect house, the perfect spouse, the perfect job, the perfect nose—even perfect happiness. Tracking Down the Source . . . Chasing after elusive ideals: Where does it come from? Who can we blame for the tormenting power of perfectionism to blight our peace of mind? Our parents? Our culture? Our “super-egos”? Maybe. But in this essay, I’m going to blame Plato. Yes, Plato. He was the philosopher who came up with the whole idea of perfection in the first place. Of course, Plato pretty much laid the foundations for Western Civilization, so it’s best not to be too hard on him. Can you imagine a world without, say, The Republic? Socrates himself? Never. Plato taught us through Socrates how to think critically, how to examine our lives. Plato had his moments. Yet, there is a downside to the great philosopher. Yes, it’s true—and I say this with relish: Plato was NOT PERFECT. |

Plato’s Flaw

Truth is, Plato left to his own devices can cause a great deal of mischief. He believed that every imperfect thing has a perfect ideal in some heavenly realm—and that only those perfect “forms” are truly, truly real. Everything else—actual people, trees, and monkeys are mere shadows of their perfect counterpart ideals. It’s as if there are perfect Greek statues lined up in the heavens—perfect body, perfect tree, perfect monkey—looking down on us in judgment.

And the more divergent something is from the perfect ideal, the less value it has. You can see the disturbing moral implications piling up here. Rabbi Bradley Shavit Artson explains this particularly well in his book God of Becoming and Relationship: The Dynamic Nature of Process Theologywhere he takes on Plato’s perfect forms. He says, “A view that elevates the ideal is profoundly mistrustful of any individuality, of people being stubbornly not the ideal, of being irreducibly unique and different. It is also important to point out that if the ideal is perfect and if the physical is denigrated, then how much more so are people who are physically disabled or socially degraded: how inferior are they!” Rabbi Artson gives a compelling argument for both process theology and Jewish thought as remedies for this huge flaw in Plato.

Thinking of Jesus may be another remedy for Plato’s obsession with abstract perfectionism and ideal forms. Jesus much preferred real, earthy, imperfect people—sinners, tax collectors and the “least of these”—to the “perfect” Pharisees. Perfect people don’t have the capacity for love like imperfect people. Jesus knew that; he knew only love is the answer to the mystery of life—not perfection.

The Consolation of Wabi Sabi

Yet another remedy for getting Mr. Perfect, aka Plato, off our backs comes from Japan. The Japanese do not revere Plato like we Westerners do. Thank goodness. When the tyranny of perfectionism hits, we can turn to the Japanese notion of wabi-sabi for consolation. What is wabi-sabi? To me, it is a bed of flowers in which to rest after typos have taken their exhausting, demoralizing toll on the spirit. Wabi-sabi is a Japanese aesthetic, a view of beauty that actually embraces imperfection.

Richard Powell, in his book Wabi Sabi Simple, explains that wabi-sabi “nurtures all that is authentic by acknowledging three simple realities: nothing lasts, nothing is finished, and nothing is perfect.” This is a Buddhist way of thinking, and the Japanese prefer this as a standard for beauty rather than Plato’s ideal forms. In a spiritual sense, wabi-sabi says to us: Perfectionists, step aside! Bring in the rustic tea pot, chipped and scarred with use; the fallen leaf, brown and withered; the old woman, wrinkled and full of history and stories. All these are beautiful, my friends, if only you could see.

As a process thinker, I am drawn to wabi-sabi. I have recently created a wabi-sabi rock garden—a simple, earthy affair of collected rocks washed in by the tide, set in the form of a spiral so it can go on and on as I find more rocks. Not only is it forever unfinished, it is also filled with diverse, rough, oddly shaped rocks of various colors and sizes—all of which somehow create a more intense harmony. This is a process view of beauty: the beauty is in the differences, like the different notes of a chord of music, each note with its own integrity—together spilling out into the air in clusters of intense harmony that further the creative advance of the universe.

Widening Circles

"I live my life in widening circles," says the poet Rilke. My wabi-sabi garden will grow in size to make room for more rocks, yet keep its integrity as a spiral. It is a rock garden in process—a widening beauty—an unfinished becoming rather than a static being. So it is with our very souls; they are not static “things.” We are not perfect, self-enclosed billiard balls bumping up against each other. We are created out of our relatedness to one another—and to the past and possible future. We are hurt by our relationships and we are healed by our relationships. And we are forever free to choose a more healing path, a more beautiful path that the one we are on.

Our souls or psyches constantly erupt into fresh becomings and can, despite the pressure of the past, re-imagine the world in widening circles. The beautiful soul, the wide soul--or what I like to call the fat soul—does not subscribe to the narrow ideals thrust upon it by the Tyranny of Thin mentality. The fat soul is one that, for the sake of love and beauty and intensity of feeling, expands to include the so-called imperfect, the not-quite-right, and the sweet but sad melancholy of “perpetual perishing.”

And so, Dear Plato . . .

Thus, beauty in terms of process thought and wabi-sabi bears scant resemblance to the Platonic ideals of abstract perfection to which we must aspire or be counted inferior. We “subversives” who stand up against the Tyranny of Thin and all the trouble perfectionism has wrought in the world, choose instead to fatten our vision, our psyches, our souls. Rather than hold ourselves up to a static, abstract perfection, we choose to embrace the warts-and-all diversity and contrasts in the real world of fresh becomings. We choose to love our unfinished selves, our bodies, our work, our relationships—all in their natural “imperfections” and unique differences. We throw out our scales and give ourselves over to a worldview with wide hips—one that can make room for all the variegated colors and shapes and striking contrasts that make life beautiful.

And so, dear Plato, father of Western Civilization, I apologize for being so hard on you. You are part of us—we Westerners, religious and secular alike, who have been raised on your static ideas of perfection. We will not abandon you. You have given us so much. After all, Whitehead said that the whole tradition of Western philosophy is a series of footnotes to you. You are simply unfinished and imperfect like the rest of us. But cheer up, Plato. Even as we declare you to be flawed as an ancient Greek statue missing an arm, in the spirit of process and wabi-sabi, we also pronounce you beautiful.

---Personal Postscript---

THERE IS A FLAW in the above essay, and it has nothing to do with typos—although there are probably several of those. After writing and re-writing and writing again, I couldn't quite get a handle on the problem. It was too deep and elusive—and subconsciously troubling. Something was wrong. In frustration, I played the video above and listened once again to Karen Carpenter sing, and I suddenly realized the problem with a jolt. Her beautiful, rich, contralto voice was the very lure I needed to say something I never dreamed of saying out-loud in public—and certainly never in writing! But her voice from "long ago and oh, so far away" insisted that what I needed to add, if I was to be true to the words above, is this: I am not merely a distant observer. I am a survivor of anorexia nervosa.

In the late 1970s (in my early-twenties) I developed the disease even while Karen Carpenter was losing her battle. She was an icon for me, someone I adored, a fellow musician. She was perfect. I wanted to be. She died and I lived. It could have been me, as we weighed exactly the same: 91 lbs. And yet, even in that emaciated state, I felt that if I just lost another pound or two, I would be perfect. It took an intervention and a stern doctor's warning that I had to choose life or die. I chose life. I was lucky to get the help I needed, but it was a long, long road to recovery. My weight eventually became normal, but I learned that you don't ever quite shake off the demons. They are always there, lurking in the shadows, but the difference is that they lose their power over your life.

Although there are many new theories about the disease, including many biological and genetic factors that doctors were not aware of in the 1970s, perfectionism and the need for control over one's life, two central features of the illness, are not only treatable but can also be transformed. I am living proof. Treatment is one thing, but transformation takes years. I'm not sure that I would have made it even to age thirty-two, the age Karen Carpenter's heart gave out, if I had not learned how to slowly transform my entire world view.

Through the years, process thought—especially process theology—helped expand my narrow, severe, impoverished view of myself, God, and the world into a lovely, widening landscape of beauty, love, and letting go. The psychological effect of process theology helped me slowly regain my health and, eventually, flourish. Yet when, as a professional minister and teacher, I encountered anorexic girls, I related to them only as an objective professional, keeping my own "imperfect" past to myself. But now I am too old and life is too short for such distance and pretense. At least that's what Karen Carpenter was telling me with her voice from somewhere in heaven.

I realize now that my essay was not so much imperfect as it was too perfect. It lacked the embodiment of my own imperfect authenticity—a personal story that might help someone who is suffering. Now, with this added postscript, the essay feels authentic, wabi-sabi—an imperfect offering.

**I borrow the title “The Beauty of Imperfection” from Frederic and Mary Ann Brusatt's insightful article which also explores some of the spiritual implications of wabi-sabi. Their wonderful website has featured my own essay The Numinosity of Rocks, as wella review of my book Embracing a Beautiful God. I encourage you to visit their site.

Truth is, Plato left to his own devices can cause a great deal of mischief. He believed that every imperfect thing has a perfect ideal in some heavenly realm—and that only those perfect “forms” are truly, truly real. Everything else—actual people, trees, and monkeys are mere shadows of their perfect counterpart ideals. It’s as if there are perfect Greek statues lined up in the heavens—perfect body, perfect tree, perfect monkey—looking down on us in judgment.

And the more divergent something is from the perfect ideal, the less value it has. You can see the disturbing moral implications piling up here. Rabbi Bradley Shavit Artson explains this particularly well in his book God of Becoming and Relationship: The Dynamic Nature of Process Theologywhere he takes on Plato’s perfect forms. He says, “A view that elevates the ideal is profoundly mistrustful of any individuality, of people being stubbornly not the ideal, of being irreducibly unique and different. It is also important to point out that if the ideal is perfect and if the physical is denigrated, then how much more so are people who are physically disabled or socially degraded: how inferior are they!” Rabbi Artson gives a compelling argument for both process theology and Jewish thought as remedies for this huge flaw in Plato.

Thinking of Jesus may be another remedy for Plato’s obsession with abstract perfectionism and ideal forms. Jesus much preferred real, earthy, imperfect people—sinners, tax collectors and the “least of these”—to the “perfect” Pharisees. Perfect people don’t have the capacity for love like imperfect people. Jesus knew that; he knew only love is the answer to the mystery of life—not perfection.

The Consolation of Wabi Sabi

Yet another remedy for getting Mr. Perfect, aka Plato, off our backs comes from Japan. The Japanese do not revere Plato like we Westerners do. Thank goodness. When the tyranny of perfectionism hits, we can turn to the Japanese notion of wabi-sabi for consolation. What is wabi-sabi? To me, it is a bed of flowers in which to rest after typos have taken their exhausting, demoralizing toll on the spirit. Wabi-sabi is a Japanese aesthetic, a view of beauty that actually embraces imperfection.

Richard Powell, in his book Wabi Sabi Simple, explains that wabi-sabi “nurtures all that is authentic by acknowledging three simple realities: nothing lasts, nothing is finished, and nothing is perfect.” This is a Buddhist way of thinking, and the Japanese prefer this as a standard for beauty rather than Plato’s ideal forms. In a spiritual sense, wabi-sabi says to us: Perfectionists, step aside! Bring in the rustic tea pot, chipped and scarred with use; the fallen leaf, brown and withered; the old woman, wrinkled and full of history and stories. All these are beautiful, my friends, if only you could see.

As a process thinker, I am drawn to wabi-sabi. I have recently created a wabi-sabi rock garden—a simple, earthy affair of collected rocks washed in by the tide, set in the form of a spiral so it can go on and on as I find more rocks. Not only is it forever unfinished, it is also filled with diverse, rough, oddly shaped rocks of various colors and sizes—all of which somehow create a more intense harmony. This is a process view of beauty: the beauty is in the differences, like the different notes of a chord of music, each note with its own integrity—together spilling out into the air in clusters of intense harmony that further the creative advance of the universe.

Widening Circles

"I live my life in widening circles," says the poet Rilke. My wabi-sabi garden will grow in size to make room for more rocks, yet keep its integrity as a spiral. It is a rock garden in process—a widening beauty—an unfinished becoming rather than a static being. So it is with our very souls; they are not static “things.” We are not perfect, self-enclosed billiard balls bumping up against each other. We are created out of our relatedness to one another—and to the past and possible future. We are hurt by our relationships and we are healed by our relationships. And we are forever free to choose a more healing path, a more beautiful path that the one we are on.

Our souls or psyches constantly erupt into fresh becomings and can, despite the pressure of the past, re-imagine the world in widening circles. The beautiful soul, the wide soul--or what I like to call the fat soul—does not subscribe to the narrow ideals thrust upon it by the Tyranny of Thin mentality. The fat soul is one that, for the sake of love and beauty and intensity of feeling, expands to include the so-called imperfect, the not-quite-right, and the sweet but sad melancholy of “perpetual perishing.”

And so, Dear Plato . . .

Thus, beauty in terms of process thought and wabi-sabi bears scant resemblance to the Platonic ideals of abstract perfection to which we must aspire or be counted inferior. We “subversives” who stand up against the Tyranny of Thin and all the trouble perfectionism has wrought in the world, choose instead to fatten our vision, our psyches, our souls. Rather than hold ourselves up to a static, abstract perfection, we choose to embrace the warts-and-all diversity and contrasts in the real world of fresh becomings. We choose to love our unfinished selves, our bodies, our work, our relationships—all in their natural “imperfections” and unique differences. We throw out our scales and give ourselves over to a worldview with wide hips—one that can make room for all the variegated colors and shapes and striking contrasts that make life beautiful.

And so, dear Plato, father of Western Civilization, I apologize for being so hard on you. You are part of us—we Westerners, religious and secular alike, who have been raised on your static ideas of perfection. We will not abandon you. You have given us so much. After all, Whitehead said that the whole tradition of Western philosophy is a series of footnotes to you. You are simply unfinished and imperfect like the rest of us. But cheer up, Plato. Even as we declare you to be flawed as an ancient Greek statue missing an arm, in the spirit of process and wabi-sabi, we also pronounce you beautiful.

---Personal Postscript---

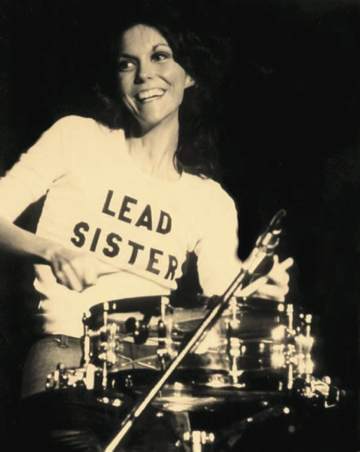

THERE IS A FLAW in the above essay, and it has nothing to do with typos—although there are probably several of those. After writing and re-writing and writing again, I couldn't quite get a handle on the problem. It was too deep and elusive—and subconsciously troubling. Something was wrong. In frustration, I played the video above and listened once again to Karen Carpenter sing, and I suddenly realized the problem with a jolt. Her beautiful, rich, contralto voice was the very lure I needed to say something I never dreamed of saying out-loud in public—and certainly never in writing! But her voice from "long ago and oh, so far away" insisted that what I needed to add, if I was to be true to the words above, is this: I am not merely a distant observer. I am a survivor of anorexia nervosa.

In the late 1970s (in my early-twenties) I developed the disease even while Karen Carpenter was losing her battle. She was an icon for me, someone I adored, a fellow musician. She was perfect. I wanted to be. She died and I lived. It could have been me, as we weighed exactly the same: 91 lbs. And yet, even in that emaciated state, I felt that if I just lost another pound or two, I would be perfect. It took an intervention and a stern doctor's warning that I had to choose life or die. I chose life. I was lucky to get the help I needed, but it was a long, long road to recovery. My weight eventually became normal, but I learned that you don't ever quite shake off the demons. They are always there, lurking in the shadows, but the difference is that they lose their power over your life.

Although there are many new theories about the disease, including many biological and genetic factors that doctors were not aware of in the 1970s, perfectionism and the need for control over one's life, two central features of the illness, are not only treatable but can also be transformed. I am living proof. Treatment is one thing, but transformation takes years. I'm not sure that I would have made it even to age thirty-two, the age Karen Carpenter's heart gave out, if I had not learned how to slowly transform my entire world view.

Through the years, process thought—especially process theology—helped expand my narrow, severe, impoverished view of myself, God, and the world into a lovely, widening landscape of beauty, love, and letting go. The psychological effect of process theology helped me slowly regain my health and, eventually, flourish. Yet when, as a professional minister and teacher, I encountered anorexic girls, I related to them only as an objective professional, keeping my own "imperfect" past to myself. But now I am too old and life is too short for such distance and pretense. At least that's what Karen Carpenter was telling me with her voice from somewhere in heaven.

I realize now that my essay was not so much imperfect as it was too perfect. It lacked the embodiment of my own imperfect authenticity—a personal story that might help someone who is suffering. Now, with this added postscript, the essay feels authentic, wabi-sabi—an imperfect offering.

**I borrow the title “The Beauty of Imperfection” from Frederic and Mary Ann Brusatt's insightful article which also explores some of the spiritual implications of wabi-sabi. Their wonderful website has featured my own essay The Numinosity of Rocks, as wella review of my book Embracing a Beautiful God. I encourage you to visit their site.

Karen Carpenter

Fresh Starts

We've only just begun. In process theology there is something metaphysically true, even ultimate, about this phrase. Truth be told, every moment is a new beginning, distinct from the past. Indeed, every moment is an act of improvising a response to what has been, in light of what can be. The same applies even to the Great Becoming, even to God. She is everlasting, to be sure. And yet in her everlasting Journey she is always fresh, always now, always free.

But it's not all that pretty. In human life the past can have its overwhelming influence, too, and sometimes it is destructive. We can be stuck in habits, physical and mental, that trap us. An eating disorder, for example. Our improvisations can be little more than repetition. Still, regardless of what has happened in the past, there is the possibility of a fresh start, coming from the Freshness Deep Down. For some of us, it takes a long time, and many mistakes, to accept the grace of a fresh start. In the case of an eating disorder, the treatment can come quickly but the transformation takes years. Karen Carpenter spent much of her life struggling to accept herself even as, along the way, she added incredible beauty to the world with her songs and (melancholy) spirit. In process theology we trust that she now rests and grows in a Beauty beyond this life. And we are ever so thankful that, as she rests and grows in that Beauty, we, too, can rest and grow in it, with help from her music, her struggle, her zest for life. The purpose of this page is to help us learn from her and her music, with help from one of our wisest of process sages, Patricia Adams Farmer, for whom Karen Carpenter was a musical mentor and who, like Karen, knew the importance of fresh starts.

But it's not all that pretty. In human life the past can have its overwhelming influence, too, and sometimes it is destructive. We can be stuck in habits, physical and mental, that trap us. An eating disorder, for example. Our improvisations can be little more than repetition. Still, regardless of what has happened in the past, there is the possibility of a fresh start, coming from the Freshness Deep Down. For some of us, it takes a long time, and many mistakes, to accept the grace of a fresh start. In the case of an eating disorder, the treatment can come quickly but the transformation takes years. Karen Carpenter spent much of her life struggling to accept herself even as, along the way, she added incredible beauty to the world with her songs and (melancholy) spirit. In process theology we trust that she now rests and grows in a Beauty beyond this life. And we are ever so thankful that, as she rests and grows in that Beauty, we, too, can rest and grow in it, with help from her music, her struggle, her zest for life. The purpose of this page is to help us learn from her and her music, with help from one of our wisest of process sages, Patricia Adams Farmer, for whom Karen Carpenter was a musical mentor and who, like Karen, knew the importance of fresh starts.

We've Only Just Begun

BBC Story of what the song

means to people around the world

We've Only Just Begun

"The Carpenters - brother and sister duo Richard and Karen - were one of the most popular groups of the 1970s. His outstanding compositions and her stunning vocals created several massive hits including We've Only Just Begun. Originally written as a TV advert for a bank portraying happy young couples embarking on married life full of hope, they loved it and released it as their third single in 1970. Karen's wistful voice gave the song a melancholy that has long resonated with fans....After her premature death from heart failure due to anorexia nervosa, the song took on an extra poignancy with lyrics like "so much of life ahead." Fans tell their stories about the song and how it relates to their own life journeys...more.

"The Carpenters - brother and sister duo Richard and Karen - were one of the most popular groups of the 1970s. His outstanding compositions and her stunning vocals created several massive hits including We've Only Just Begun. Originally written as a TV advert for a bank portraying happy young couples embarking on married life full of hope, they loved it and released it as their third single in 1970. Karen's wistful voice gave the song a melancholy that has long resonated with fans....After her premature death from heart failure due to anorexia nervosa, the song took on an extra poignancy with lyrics like "so much of life ahead." Fans tell their stories about the song and how it relates to their own life journeys...more.

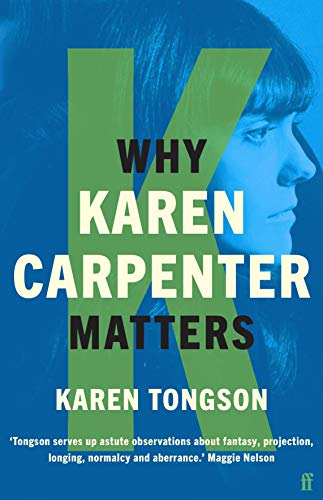

Why Karen Carpenter Matters

|

"The book is equal parts memoir and character study, as we’re treated to the author’s personal history with the music. Having an affinity for the music because it’s important to your cultural heritage is one thing. But it’s something else entirely to have the music swirl around you constantly because your entire family performs the songs as part of its live act for a large swath of your childhood. |

Tongson then outlines myriad instances in her youth and adolescence when she tried to introduce The Carpenters to her friends. I related to those stories of slipping in music that you knew wasn’t necessarily cool, but you loved anyway because you hoped to make new converts.

The author also talks about how she related to Karen’s tomboy nature, specifically her love of culturally masculine symbols like sports (especially baseball), jeans, and drumming. She speaks openly about how she and other LQBTQ+ persons have for decades used Karen as a totem for coming to understand themselves and their identities in a world that tries to shove people into harmful and hurtful binaries."

- Book review by Adam Newton: click here.

BBC Commentary on Karen Carpenter

|

|

|