- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

No and Yes

A Process Appreciation

The process movement orients itself around four hopes: whole persons, whole communities, a whole planet, and holistic thinking. It recognizes that whole persons need whole communities and a whole planet, and the other way around. And with its emphasis on relationality, it quickly emphasizes that many relationships are toxic not healthy. One form of toxicity, found throughout the world, is patriarchy. Another form, unique to western society, is a culture that equates slimness with beauty.

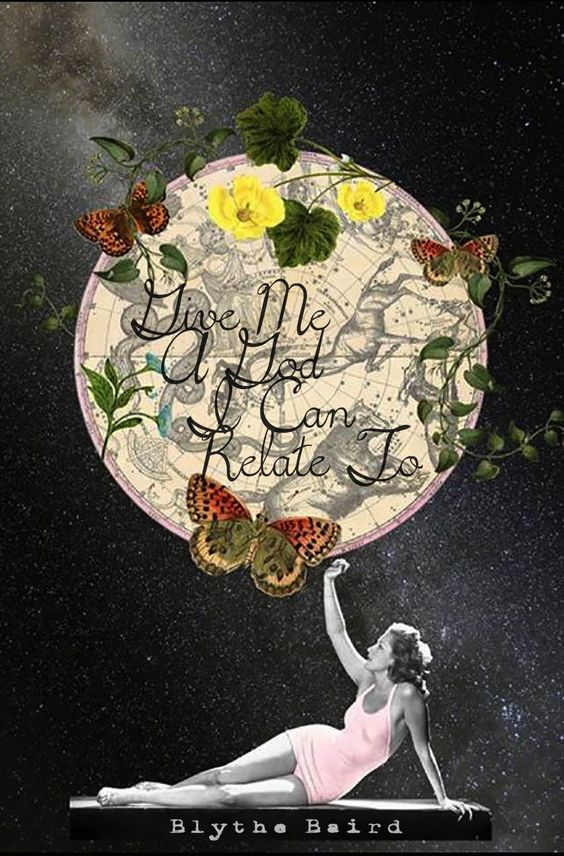

Blythe Baird speaks to both of these toxicities in the poems on this page: When the Fat Girl Gets Skinny and Pocket Size-Feminism. You sense a connection between the two, how eating disorders reflect a world dominated by toxic ideals of beauty internalized by women and valorized by men.

Process theologians often speak of the divine as a lure toward wholeness within and beyond human life: in people, to be sure, and in a different way in other animals and the earth, Indeed, they see this lure in the galaxies as well.

Saying "yes" to the lure means saying "no" to the toxicities. The "no" can take the form of active resistance at a personal and political level, and also at a poetic level. This resistance is more than moralizing. It is story-telling: that is, telling what it is like to be "a fat girl who gets skinny" and to be someone who is raped or assaulted, perpetually subjected to an unhealthy and controlling male gaze.

Poetic resistance is as important as political resistance; it creates a space for new ways of being and forms of consciousness to emerge, for people of all genders: ways and forms that embody the kinds of transformations so important to our time. These new ways are hopeful, but there can be no hope without the resistance, without the stories, without the "no."

Blythe Baird speaks to both of these toxicities in the poems on this page: When the Fat Girl Gets Skinny and Pocket Size-Feminism. You sense a connection between the two, how eating disorders reflect a world dominated by toxic ideals of beauty internalized by women and valorized by men.

Process theologians often speak of the divine as a lure toward wholeness within and beyond human life: in people, to be sure, and in a different way in other animals and the earth, Indeed, they see this lure in the galaxies as well.

Saying "yes" to the lure means saying "no" to the toxicities. The "no" can take the form of active resistance at a personal and political level, and also at a poetic level. This resistance is more than moralizing. It is story-telling: that is, telling what it is like to be "a fat girl who gets skinny" and to be someone who is raped or assaulted, perpetually subjected to an unhealthy and controlling male gaze.

Poetic resistance is as important as political resistance; it creates a space for new ways of being and forms of consciousness to emerge, for people of all genders: ways and forms that embody the kinds of transformations so important to our time. These new ways are hopeful, but there can be no hope without the resistance, without the stories, without the "no."