Dear Process Friends,

I'm afraid Whitehead's philosophy seems reductionist to many of my friends. It reduces lived human experience to non-human "building blocks" he calls actual entities. Can Whitehead's philosophy be articulated in a way that would make sense to the people in these photographs? Or is it primarily about very small actual entities, devoid of personal qualities, that are somehow combined to create a human life? I look forward to your response.

Whiteheadian

*

Dear Whiteheadian,

John Cobb says that in Process and Reality there are two primary examples of 'actual entities." One is, as you say, a very small event in the depths of an atom. The other is a single moment of human experience and, by extension, animal experience. Some people neglect the example of lived human experience; they read Whitehead from a third-person persoective, as if his analysis of concrescence and its feelings is only about very small bursts of energy. But we recommend reading Whitehead from both perspectives, taking all of his ideas and seeing if they might illuminate lived human experience. We think Whitehead would appreciate what we are saying. We see him as doing what philosophers call phenomenology: describing lived experience. This page is for you,

Open Horizons

I'm afraid Whitehead's philosophy seems reductionist to many of my friends. It reduces lived human experience to non-human "building blocks" he calls actual entities. Can Whitehead's philosophy be articulated in a way that would make sense to the people in these photographs? Or is it primarily about very small actual entities, devoid of personal qualities, that are somehow combined to create a human life? I look forward to your response.

Whiteheadian

*

Dear Whiteheadian,

John Cobb says that in Process and Reality there are two primary examples of 'actual entities." One is, as you say, a very small event in the depths of an atom. The other is a single moment of human experience and, by extension, animal experience. Some people neglect the example of lived human experience; they read Whitehead from a third-person persoective, as if his analysis of concrescence and its feelings is only about very small bursts of energy. But we recommend reading Whitehead from both perspectives, taking all of his ideas and seeing if they might illuminate lived human experience. We think Whitehead would appreciate what we are saying. We see him as doing what philosophers call phenomenology: describing lived experience. This page is for you,

Open Horizons

Where is Lived, Human Experience

in Whitehead's Philosophy?

Answer: It's in the moment, whether drunk or sober,

intellectual or physical, happy or grieving.

An immediate human experience

is itself an actual entity.

The Elucidation of Immediate Experience

The elucidation of immediate experience is the sole justification for any thought; and the starting-point for thought is the analytic observation of components of this experience. (Whitehead, Alfred North. Process and Reality)

Nothing can be omitted.

Nothing can be omitted, experience drunk and experience sober, experience sleeping and experience waking, experience drowsy and experience wide-awake, experience self-conscious and experience self-forgetful, experience intellectual and experience physical, experience religious and experience sceptical, experience anxious and experience care-free, experience anticipatory and experience retrospective, experience happy and experience grieving, experience dominated by emotion and experience under self-restraint, experience in the light and experience in the dark, experience normal and experience abnormal. (Whitehead, Adventures of Ideas)

Dogs have lived experience, too.Actual occasions are the actual entities of which the world, meaning thereby this cosmos and any other cosmos that may have been, may now be, or may come to be, is composed. This is a sharp challenge to most of the Western tradition and to the “common sense” inculcated in us by our language. When we say, “the dog barks,” or “the rug is blue,” most of us think of the dog and the rug as actual entities. Whitehead disagrees. To understand his thought we must shift from giving priority to what most of our nouns, such as “dog” and “rug” designate to the experience of the one who hears the barking of the dog or sees the blueness of the rug. The dog-as-barking and the rug-as-blue are abstractions from the experience of the individual who is hearing or seeing. It is the experience of the individual that is fully actual. However, once we understand what kind of thing is actual, we can find actuality also in the barking dog and the blue rug. With the barking dog it is easier. Common sense suggests that the dog is not exhausted by an observer’s hearing the barking. The dog also has a point of view. At any given moment there is the dog’s experience as well as the observer’s. The dog’s experience, in each moment, is just as much an actual occasion as is the experience of the human observer. (John Cobb, Whitehead Word Book) |

And so do quantum events.The two clearest examples of actual occasions are, thus, a momentary experience, whether of a human being or of some other animal, and a quantum of energy. By giving them the same name, Whitehead calls attention to what, with all their differences, they have in common. First, we may point out what they are not. They are not “matter” in the Greek or the modern sense. That is, they are not passive recipients of form or action. They act to constitute themselves as what they become. Second, they become what they become out of a given world. What they are is largely a function of what other things are. In the case of the quantum, it is what it is largely because of the quantum field in which it occurs. In the case of a moment of human experience, it is what it is largely because of the character and content of antecedent human experiences and the neuronal events in the brain. A Moment of Lived Experience in Whiteheadian Perspective |

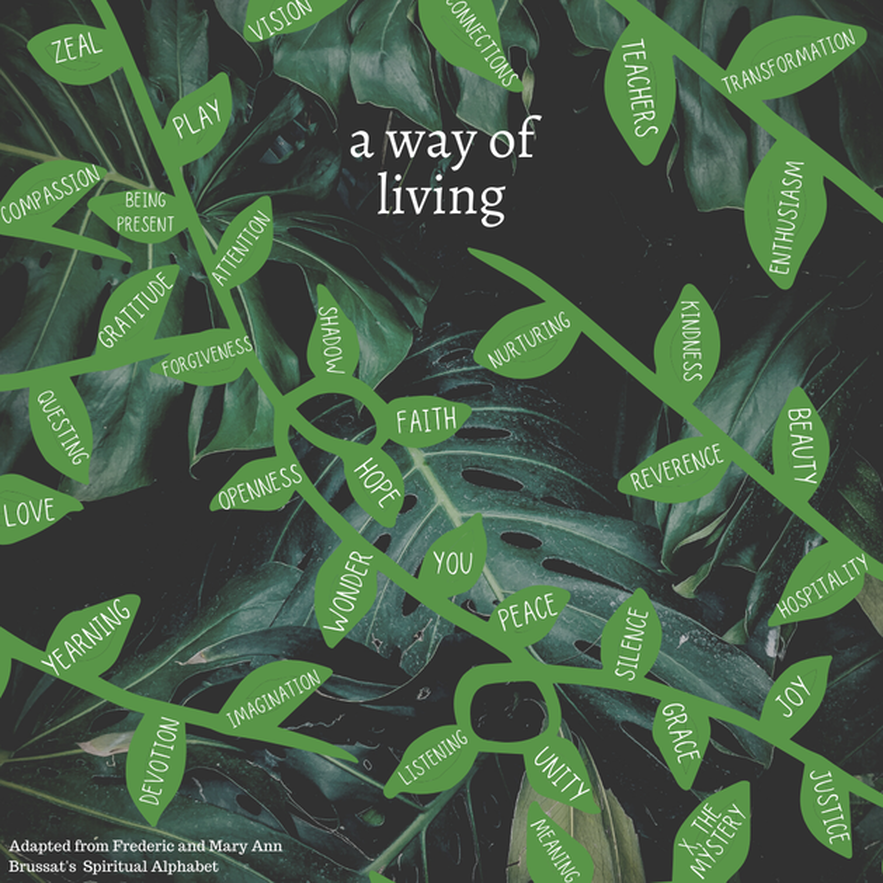

What are healthy or life-nourishing forms of experience?

Lived human experience can include many negative emotions: hatred, confusion and greed, for example. Buddhism talks about these as the three poisons. Lived human experience can also include many more positive emotions. (Whitehead calls them subjective forms.)

The Cobb Institute defines 'spiritual integration' as embodied wisdom and emotional intelligence in daily life. Click here. The Berkeley Center for the Greater Good (associated with the University of California at Berkeley) shows how these modes of experience can be understood with help from positive psychology, anthropology, sociology, and neural science. Click here.

Here are some examples:

Can God be experienced and does God have experiences?

From Whitehead's perspective the answer is 'yes' to both questions.

If, along with Whitehead, we understand God as the mind of the universe (primordial nature of God) and an everlasting companion to the world's joys and sufferings (consequent nature) and as in inwardly felt lure toward truth and goodness and beauty (superjective nature) then God has experiences. Or, perhaps better, God is a concrescing subject, embracing the whole of the cosmos, who is these experiences.

Whitehead says pretty clearly in Process and Reality that God prehends or feels both the realm of pure potentialities (eternal objects) and the world of experience (moments of experience in the lives of human beings and all other creatures" with a "tender care that nothing be lost."

So the question becomes, can God as understood in this way be experienced by human beings? For Whitehead, the answer is 'yes' in two ways. We experience God through the ideals of truth, goodness and beauty and (so John Cobb adds) through 'initial aims' or fresh possibilities available in the situation at hand which are tailored to the situation at hand. In much of his later works John Cobb emphasizes that these fresh possibilities are often for what he calls creative transformation. And, for Whitehead, we experience God through an intuition of Peace: that is, an intuition that we live and move and have our being in a cosmic harmony: a harmony of harmonies which has its own beauty.

Other Whiteheadians add that we can experience God in many other ways. For example, at a communal level, we experience God through the prophetic imagination, which as two sides. The biblical scholar Walter Brueggeman calls them prophetic anunciation and prophetic denunciation. Prophetic annunciation is the imagining of a world that is just, sustainable and joyful, a world of nurturing communities where no one is left behind and the other animals and the earth are treated with respect. It is hopeful, and often cast in terms of an alternative to the status quo. Prophetic denunciation is a critique of the status quo when it falls short of this ideal and foments hatred, cruelty, domination, and injustice. For more on this, see John Cobb's Salvation: Salvation. Jesus' Mission and Ours, which includes both sides. The efforts of the Cobb Institute to promote and encourage a compassionate Pomona are a collective way of experiencing God through social critique and community development. Pope Francis calls it "integral ecology.'

At a personal level, so Cobb and others say, we experience God through the enjoyment of many of forms of embodied wisdom named above. All can be ways of participating in, and knowing, God. All are forms of wholeness. See again the Cobb Institute's statement on spirituality.

What about mysticism? So much depends on how it is defined. In Open Horizons a page is offered called Eight Forms of Mysticism. Some of these forms are examples of experiencing God and some are examples of experiencing other kinds of reality. All can be valuable. Here we are rightly reminded that not all forms of religious experience need to be 'about' God. For Whiteheadian's, God is not jealous and God does not seek flattery. If a person experiences the absolute inter-becoming of all things in the immediacy of the moment, such that the self momentarily drops away, this is mysticism but it is not necessarily about God. It is about inter-becoming.

A final cautionary note. No particular experience ought to be understood as free of perspective, error, and self-delusion. It can seem to many that they are experiencing "God" when in fact they are experiencing their own collective or individual egos. And sometimes they are experiencing forces of evil in the world which they misname God. These forces are real, but they are not manifestations of God. God is good and not all-powerful. There are many things that happen in the world that are not God: violence, abuse, cruelty, violations of integrity, greed, hatred, and falsehoods. Hence the importance of what the Christian tradition calls 'discernment.' The Whiteheadian guideline is that if the experience is of love and from love, or leads to a life of love, it is of God and from God. If it is of hatred or leads to hatred, it is not of God or from God, regardless of its power. Let God be God, say the Whiteheadians, and let God be love.

If, along with Whitehead, we understand God as the mind of the universe (primordial nature of God) and an everlasting companion to the world's joys and sufferings (consequent nature) and as in inwardly felt lure toward truth and goodness and beauty (superjective nature) then God has experiences. Or, perhaps better, God is a concrescing subject, embracing the whole of the cosmos, who is these experiences.

Whitehead says pretty clearly in Process and Reality that God prehends or feels both the realm of pure potentialities (eternal objects) and the world of experience (moments of experience in the lives of human beings and all other creatures" with a "tender care that nothing be lost."

So the question becomes, can God as understood in this way be experienced by human beings? For Whitehead, the answer is 'yes' in two ways. We experience God through the ideals of truth, goodness and beauty and (so John Cobb adds) through 'initial aims' or fresh possibilities available in the situation at hand which are tailored to the situation at hand. In much of his later works John Cobb emphasizes that these fresh possibilities are often for what he calls creative transformation. And, for Whitehead, we experience God through an intuition of Peace: that is, an intuition that we live and move and have our being in a cosmic harmony: a harmony of harmonies which has its own beauty.

Other Whiteheadians add that we can experience God in many other ways. For example, at a communal level, we experience God through the prophetic imagination, which as two sides. The biblical scholar Walter Brueggeman calls them prophetic anunciation and prophetic denunciation. Prophetic annunciation is the imagining of a world that is just, sustainable and joyful, a world of nurturing communities where no one is left behind and the other animals and the earth are treated with respect. It is hopeful, and often cast in terms of an alternative to the status quo. Prophetic denunciation is a critique of the status quo when it falls short of this ideal and foments hatred, cruelty, domination, and injustice. For more on this, see John Cobb's Salvation: Salvation. Jesus' Mission and Ours, which includes both sides. The efforts of the Cobb Institute to promote and encourage a compassionate Pomona are a collective way of experiencing God through social critique and community development. Pope Francis calls it "integral ecology.'

At a personal level, so Cobb and others say, we experience God through the enjoyment of many of forms of embodied wisdom named above. All can be ways of participating in, and knowing, God. All are forms of wholeness. See again the Cobb Institute's statement on spirituality.

What about mysticism? So much depends on how it is defined. In Open Horizons a page is offered called Eight Forms of Mysticism. Some of these forms are examples of experiencing God and some are examples of experiencing other kinds of reality. All can be valuable. Here we are rightly reminded that not all forms of religious experience need to be 'about' God. For Whiteheadian's, God is not jealous and God does not seek flattery. If a person experiences the absolute inter-becoming of all things in the immediacy of the moment, such that the self momentarily drops away, this is mysticism but it is not necessarily about God. It is about inter-becoming.

A final cautionary note. No particular experience ought to be understood as free of perspective, error, and self-delusion. It can seem to many that they are experiencing "God" when in fact they are experiencing their own collective or individual egos. And sometimes they are experiencing forces of evil in the world which they misname God. These forces are real, but they are not manifestations of God. God is good and not all-powerful. There are many things that happen in the world that are not God: violence, abuse, cruelty, violations of integrity, greed, hatred, and falsehoods. Hence the importance of what the Christian tradition calls 'discernment.' The Whiteheadian guideline is that if the experience is of love and from love, or leads to a life of love, it is of God and from God. If it is of hatred or leads to hatred, it is not of God or from God, regardless of its power. Let God be God, say the Whiteheadians, and let God be love.