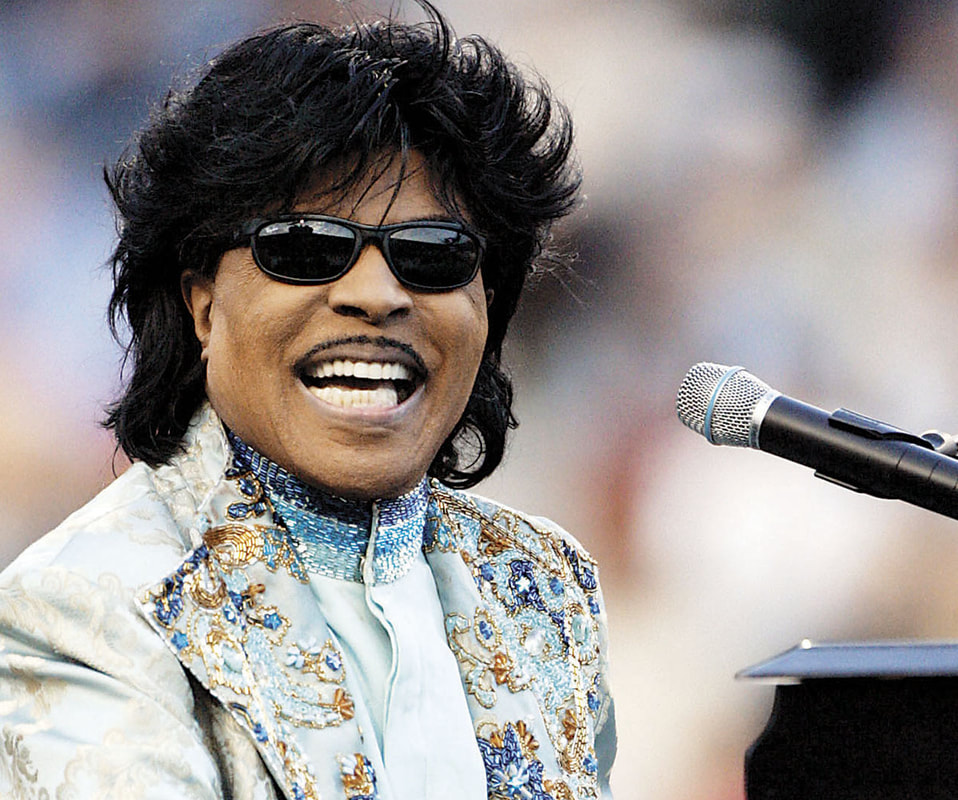

Whitehead and Little Richard

a hunger for intensity, human and divine

Was Heaven prepared for Richard Penniman (Little Richard)? He went to heaven in 2020 at at 87. I think so, but I suspect some of the angels were a little shocked. Ann Powers of NPR speaks of him as an unstoppable libinous superstar. He was so bodily and so intense! It must have shocked a few of the more prudish angels who enjoy being spirits without bodies. But I think God understood fully. After all, isn't the universe itself God's body? Here I learn from the philosopher Alfred North Whitehead, who speaks of the unfolding universe itself as part of God's own life.

Whitehead also speaks of "appetitions constituting the primordial nature of God." These appetitions are for intense experience. We humans feel these divine appetitions -- these divine hungers, these divine desires -- within the depths of our own experience. Moment by moment. say process theologians, God's appetitions are the "initial aims" for intense feeling, for full aliveness, that we ourselves feel relative to the situations we face. The aims are tailored to our own immediate situation. We feel these fresh possibilities with emotions, subjective forms, conformal to God's own emotions, We share in God's appetite for intensity.

When I say "moments" I mean what Whitehead called actual occasions of experience. In A Christian Natural Theology John Cobb explains the relation between God's desire for intensity and our own desires for intensity as follows:

Whitehead speaks of God as having, like all actual entities, an aim at intensity of feeling. (PR 160-161.) In terms of the developed value theory of Adventures of Ideas, we may say his aim is at strength of beauty. This aim is primordial and unchanging, and it determines the primordial ordering of eternal objects.

But if this eternal ordering is to have specified efficacy for each new occasion, then the general aim by which it is determined must be specified to each occasion. That is, God must entertain for each new occasion the aim for its ideal satisfaction. Such an aim is the feeling of a proposition of which the novel occasion is the logical subject and the appropriate eternal object is the predicate. The subjective form of the propositional feeling is appetition, that is, the desire for its realization. (John Cobb in A Christian Natural Theology)

In religious and cultural traditions that emphasize self-sacrifice, this natural and divine desire for intense feeling is too easily forgotten. We fall into thinking that God does not want us to be fully alive, to be fully embodied in our own unique ways, to say "yes" to life. We forget that in the spiritual alphabet of humanity, "Z" is for zeal or zest for life and that this zest includes the sexual and erotic side of life.

There is something inhumane about this forgetfulness and undivine as well. Little Richard may have suffered from this conflict. Growing up a Pentecostal Christian, he knew the value of intensity in worship: shouting and clapping and whooping. He knew that we could praise God with our passions. And yet he was also shaped by religious traditions that condemned any forms of sexuality other than heterosexuality, and he suffered from this. He described himself variously as gay and as polyamorous. He was married and had a son. But what he gave to the world, through his performances, was an invitation to claim the desire for intensity, even amid the conflict.

Ann Powers puts it this way:

In the original, explicit version of what would become his breakthrough hit "Turri Frutti”—a song that defines the spirit of rock and roll as succinctly as did anything by Elvis or the Beatles—the unstoppably libidinal superstar Little Richard called his music’s (and life’s) governing force “good booty.” Within those two words are all the glories and contradictions raised—aroused—by American eroticism as expressed through popular music. There’s the unapologetic crudeness, an openness that refuses to veil sex in niceties. There is an acknowledgment that this is also a realm of commerce and plunder, of booty earned and stolen. There is, of course, that reference to the ass, the centrifuge in a dancer’s body, which can be both an exploited fetish object and a partner’s cherished. private pleasure. And there is the assurance that, fundamentally, the desire for the erotic is good, something that can make a person whole, make them shout and sing. (Powers, Ann. Good Booty: Love and Sex, Black and White, Body and Soul in American Music . HarperCollins. Kindle Edition. )

Is this true? Is the desire for the erotic good and perhaps also sacred. It certainly is, when combined with respect and love. Blind eroticism that makes an object of all things is unholy, but loving eroticism is holy indeed. I'm not sure what the angels say about the erotic side of life, but it seems to me that the One in whose heart the universe unfolds, whose very body is the universe itself, and who is an eternal companion to the world's joys and sufferings, will say, along with Little Richard, "Yes, it is good."

Whitehead also speaks of "appetitions constituting the primordial nature of God." These appetitions are for intense experience. We humans feel these divine appetitions -- these divine hungers, these divine desires -- within the depths of our own experience. Moment by moment. say process theologians, God's appetitions are the "initial aims" for intense feeling, for full aliveness, that we ourselves feel relative to the situations we face. The aims are tailored to our own immediate situation. We feel these fresh possibilities with emotions, subjective forms, conformal to God's own emotions, We share in God's appetite for intensity.

When I say "moments" I mean what Whitehead called actual occasions of experience. In A Christian Natural Theology John Cobb explains the relation between God's desire for intensity and our own desires for intensity as follows:

Whitehead speaks of God as having, like all actual entities, an aim at intensity of feeling. (PR 160-161.) In terms of the developed value theory of Adventures of Ideas, we may say his aim is at strength of beauty. This aim is primordial and unchanging, and it determines the primordial ordering of eternal objects.

But if this eternal ordering is to have specified efficacy for each new occasion, then the general aim by which it is determined must be specified to each occasion. That is, God must entertain for each new occasion the aim for its ideal satisfaction. Such an aim is the feeling of a proposition of which the novel occasion is the logical subject and the appropriate eternal object is the predicate. The subjective form of the propositional feeling is appetition, that is, the desire for its realization. (John Cobb in A Christian Natural Theology)

In religious and cultural traditions that emphasize self-sacrifice, this natural and divine desire for intense feeling is too easily forgotten. We fall into thinking that God does not want us to be fully alive, to be fully embodied in our own unique ways, to say "yes" to life. We forget that in the spiritual alphabet of humanity, "Z" is for zeal or zest for life and that this zest includes the sexual and erotic side of life.

There is something inhumane about this forgetfulness and undivine as well. Little Richard may have suffered from this conflict. Growing up a Pentecostal Christian, he knew the value of intensity in worship: shouting and clapping and whooping. He knew that we could praise God with our passions. And yet he was also shaped by religious traditions that condemned any forms of sexuality other than heterosexuality, and he suffered from this. He described himself variously as gay and as polyamorous. He was married and had a son. But what he gave to the world, through his performances, was an invitation to claim the desire for intensity, even amid the conflict.

Ann Powers puts it this way:

In the original, explicit version of what would become his breakthrough hit "Turri Frutti”—a song that defines the spirit of rock and roll as succinctly as did anything by Elvis or the Beatles—the unstoppably libidinal superstar Little Richard called his music’s (and life’s) governing force “good booty.” Within those two words are all the glories and contradictions raised—aroused—by American eroticism as expressed through popular music. There’s the unapologetic crudeness, an openness that refuses to veil sex in niceties. There is an acknowledgment that this is also a realm of commerce and plunder, of booty earned and stolen. There is, of course, that reference to the ass, the centrifuge in a dancer’s body, which can be both an exploited fetish object and a partner’s cherished. private pleasure. And there is the assurance that, fundamentally, the desire for the erotic is good, something that can make a person whole, make them shout and sing. (Powers, Ann. Good Booty: Love and Sex, Black and White, Body and Soul in American Music . HarperCollins. Kindle Edition. )

Is this true? Is the desire for the erotic good and perhaps also sacred. It certainly is, when combined with respect and love. Blind eroticism that makes an object of all things is unholy, but loving eroticism is holy indeed. I'm not sure what the angels say about the erotic side of life, but it seems to me that the One in whose heart the universe unfolds, whose very body is the universe itself, and who is an eternal companion to the world's joys and sufferings, will say, along with Little Richard, "Yes, it is good."