Reading Whitehead

in an Octavian Way

Octavia Butler inspires countless numbers of people around the world. Needless to say, she does this quite apart from any connections her ideas and stories might have with the philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead. Nevertheless, given her power as an author, she can also inspire people to read Whitehead's Process and Reality in an Octavian way: not as a literal map of reality, but as an essay in speculative fiction, exploring possible ways of understanding the world. Whereas characters in Butler's fiction are people and other sentient beings, characters in Whitehead's philosophy are ideas. But both the characters and the stories are, in Whitehead's words, "lures for feeling" and both tell stories. Ideas, after all, tell stories, too. Stories about what might be the case, even if not actually the case. Characters do the same.

Sometimes Butler's stories and Whitehead's stories overlap. Both emphasize process or change, the intrinsic value of life, the interconnectedness of all things, and the damage done when authoritarian approaches to life hold sway. What is important, however, is to understand Butler's and Whitehead's work as stories: not objects to cling to, as if they were infallible dogmas, but evocations for wise, compassionate, and resilient living in challenging times. This page offers springboards for thought about Butler and Whitehead.

*

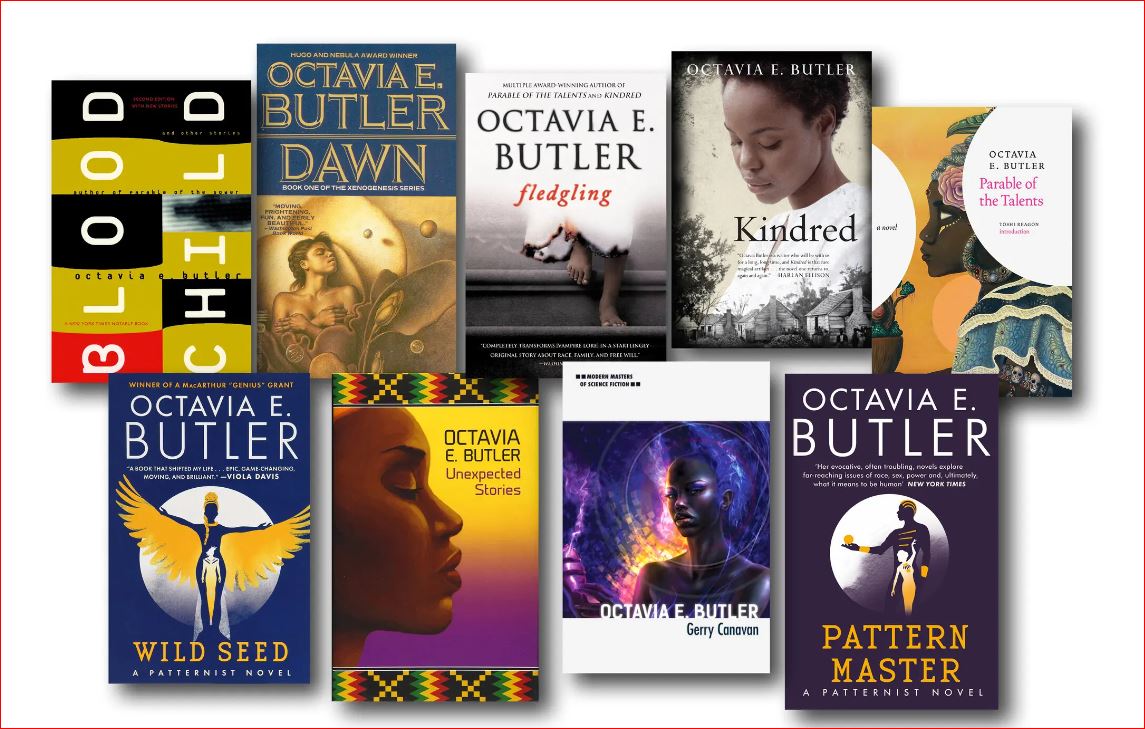

For a consideration of the relevance of Butler in her own right, I recommend her books, of course, along with the podcast series called Octavia Tried to Tell Us, co-hosted by Tananarive Due and Monica A. Coleman—prominent Black authors with specialties in horror and theology, respectively, along with six books they recommend:

A Handful of Earth, A Handful of Sky: The World of Octavia Butler

By Lynell George

Octavia's Brood: Science Fiction Stories from Social Justice Movements

By Walidah Imarisha and adrienne maree brown

Luminescent Threads: Connections to Octavia E. Butler

By Alexandra Pierce and Mimi Mondal

Conversations With Octavia Butler

By Consuela Francis

Changing Bodies in the Fiction of Octavia Butler: Slaves, Aliens, and Vampires

By Gregory Jerome Hampton

Strange Matings: Science Fiction, Feminism, African American Voices, and Octavia E. Butler

By Rebecca J. Holden and Nisi Shawl

I also recommend the BBC podcast below, featuring Irenosen Okojie, the scholar Gerry Canavan, and Nisi Shawl, writer, editor, journalist – and long-time friend of Octavia Butler. And, of course, the 2005 interview with Octavia Butler below along with her books. And for a consideration of Whitehead's ideas, scroll down for a list of twenty key ideas at the bottom of this page.

Whitehead as Speculative Fiction

Science fiction is speculative fiction. Whitehead's cosmology is speculative cosmology. It is possible and desirable to imagine Whitehead's philosophy as a form of speculative fiction. A philosophical version of ideas found in Octavio Butler's Parable of the Sower, but not quite as interesting.

*

In Plato's "Timaeus," the leading speaker describes the account he is about to give as a “likely account” (eikôs logos) or “likely story” (eikôs muthos). By this, he means that the story he is about to tell, about how the demiurge (a finite deity) forms the world, is, to his mind, plausible but not certain. However, the image of cosmology, whether Plato's or anyone else's, as a likely story invites us to consider the possibility that all cosmologies, even the most informed and complex, are, in fact, stories. Perhaps likely, but still stories. The account of "reality" Whitehead offers in "Process and Reality" is such a story.

*

Sometimes, when I am reading Whitehead's "Process and Reality," I interpret it as a form of speculative fiction, not unlike a really good novel by Octavia Butler or J.R.R. Tolkien. It explores truths of possibility that may or may not correspond to the world of actual facts but are interesting in their own right and challenge existing assumptions and expectations. When read as speculative philosophy, his philosophy takes its place alongside other genres of speculative fiction: science fiction, fantasy fiction, horror, alternative history, and dystopian fiction. Whitehead finds his place alongside authors like Butler, Tolkien, George Orwell, and Margaret Atwood.

Interestingly, Whitehead describes his own philosophy as "speculative philosophy." He acknowledges that it is but a likely story concerning what the world is like, much like Plato in the "Timaeus" speaks of his own account of the origins of the world as such a story. Given the speculative nature of his philosophy, Whitehead asserts that any hint of dogmatic certainty about the finality of a statement is an exhibition of folly. He writes:

"There remains the final reflection, how shallow, puny, and imperfect our efforts are to sound the depths in the nature of things. In philosophical discussion, the merest hint of dogmatic certainty as to the finality of a statement is an exhibition of folly."

It seems to me that if those of us influenced by Whitehead read his philosophy as speculative fiction, we might better avoid the folly of which he speaks. We may find many of his ideas plausible and helpful, but we should hold onto them with a relaxed grasp, knowing that the depths in the nature of things may elude his ideas altogether or be of a very different order. His ideas are best understood as plausible possibilities, but nothing more. The world always transcends his ideas.

*

Whitehead's philosophy invites an appreciation of truths of possibility, even if they do not correspond to the world of actuality. He writes: "In the real world, it is more important that a proposition be interesting than that it be true. The importance of truth is that it adds to interest." In Whitehead's philosophy, a proposition is an idea that functions, in his words, as a "lure for feeling." In a Whiteheadian context, feeling includes acts of thinking, imagining, remembering. Whitehead's philosophy is exactly this. An invitation to think about and imagine the cosmos in an organic way.

*

Many people who are influenced by Whitehead do not think of his philosophy as fiction. They think of it as a conceptual cartography, a map, intended to re-present the actual world or, to be more accurate, the actual multiverse. They believe that its general principles can function as guidelines for living in the world. His ideas can help us recognize the world as an interconnected, evolving whole, in which all entities are present in one another, imbued with intrinsic value (value for themselves), and advancing into an indeterminate future, guided but not controlled by a healing and creative spirit. They believe that even this spirit is in a process of change. God is temporal, they say.

But is this not also a story? Indeed, isn't it a story not unlike what we sometimes find, told more brilliantly, in novels by Octavia Butler and others. Maybe a likely story, but a story. The characters in Whitehead's story are abstract ideas, whereas the characters in Butler's fiction are people who have ideas.

= Jay McDaniel

*

In Plato's "Timaeus," the leading speaker describes the account he is about to give as a “likely account” (eikôs logos) or “likely story” (eikôs muthos). By this, he means that the story he is about to tell, about how the demiurge (a finite deity) forms the world, is, to his mind, plausible but not certain. However, the image of cosmology, whether Plato's or anyone else's, as a likely story invites us to consider the possibility that all cosmologies, even the most informed and complex, are, in fact, stories. Perhaps likely, but still stories. The account of "reality" Whitehead offers in "Process and Reality" is such a story.

*

Sometimes, when I am reading Whitehead's "Process and Reality," I interpret it as a form of speculative fiction, not unlike a really good novel by Octavia Butler or J.R.R. Tolkien. It explores truths of possibility that may or may not correspond to the world of actual facts but are interesting in their own right and challenge existing assumptions and expectations. When read as speculative philosophy, his philosophy takes its place alongside other genres of speculative fiction: science fiction, fantasy fiction, horror, alternative history, and dystopian fiction. Whitehead finds his place alongside authors like Butler, Tolkien, George Orwell, and Margaret Atwood.

Interestingly, Whitehead describes his own philosophy as "speculative philosophy." He acknowledges that it is but a likely story concerning what the world is like, much like Plato in the "Timaeus" speaks of his own account of the origins of the world as such a story. Given the speculative nature of his philosophy, Whitehead asserts that any hint of dogmatic certainty about the finality of a statement is an exhibition of folly. He writes:

"There remains the final reflection, how shallow, puny, and imperfect our efforts are to sound the depths in the nature of things. In philosophical discussion, the merest hint of dogmatic certainty as to the finality of a statement is an exhibition of folly."

It seems to me that if those of us influenced by Whitehead read his philosophy as speculative fiction, we might better avoid the folly of which he speaks. We may find many of his ideas plausible and helpful, but we should hold onto them with a relaxed grasp, knowing that the depths in the nature of things may elude his ideas altogether or be of a very different order. His ideas are best understood as plausible possibilities, but nothing more. The world always transcends his ideas.

*

Whitehead's philosophy invites an appreciation of truths of possibility, even if they do not correspond to the world of actuality. He writes: "In the real world, it is more important that a proposition be interesting than that it be true. The importance of truth is that it adds to interest." In Whitehead's philosophy, a proposition is an idea that functions, in his words, as a "lure for feeling." In a Whiteheadian context, feeling includes acts of thinking, imagining, remembering. Whitehead's philosophy is exactly this. An invitation to think about and imagine the cosmos in an organic way.

*

Many people who are influenced by Whitehead do not think of his philosophy as fiction. They think of it as a conceptual cartography, a map, intended to re-present the actual world or, to be more accurate, the actual multiverse. They believe that its general principles can function as guidelines for living in the world. His ideas can help us recognize the world as an interconnected, evolving whole, in which all entities are present in one another, imbued with intrinsic value (value for themselves), and advancing into an indeterminate future, guided but not controlled by a healing and creative spirit. They believe that even this spirit is in a process of change. God is temporal, they say.

But is this not also a story? Indeed, isn't it a story not unlike what we sometimes find, told more brilliantly, in novels by Octavia Butler and others. Maybe a likely story, but a story. The characters in Whitehead's story are abstract ideas, whereas the characters in Butler's fiction are people who have ideas.

= Jay McDaniel