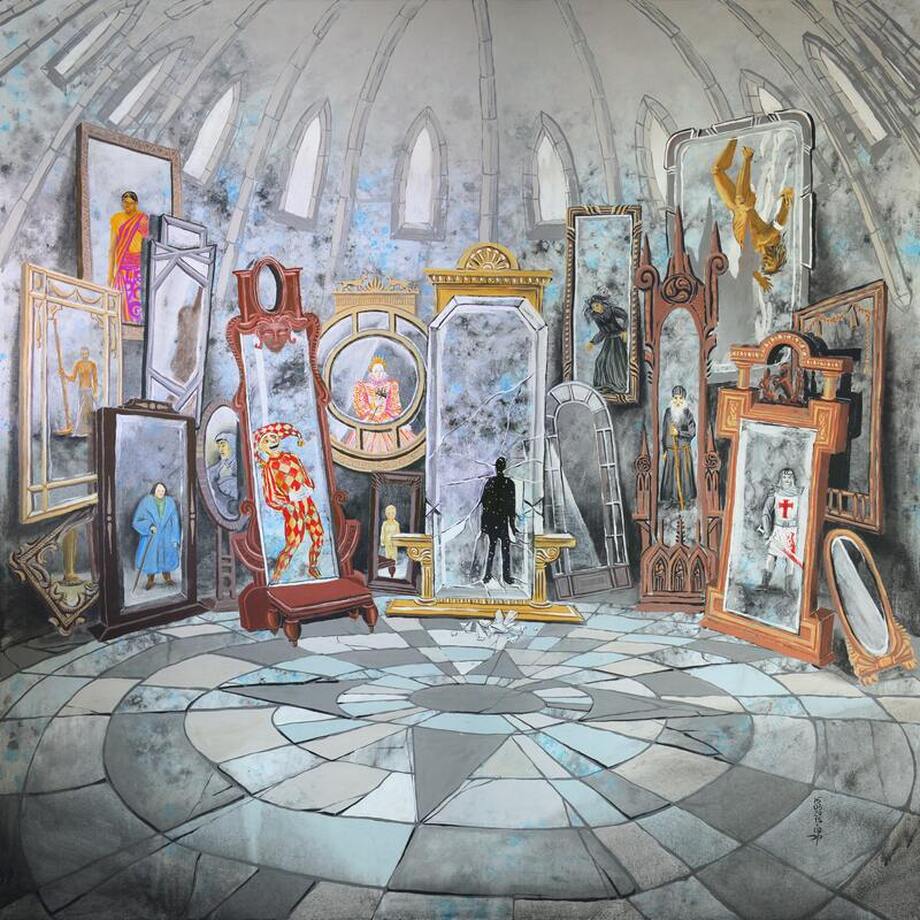

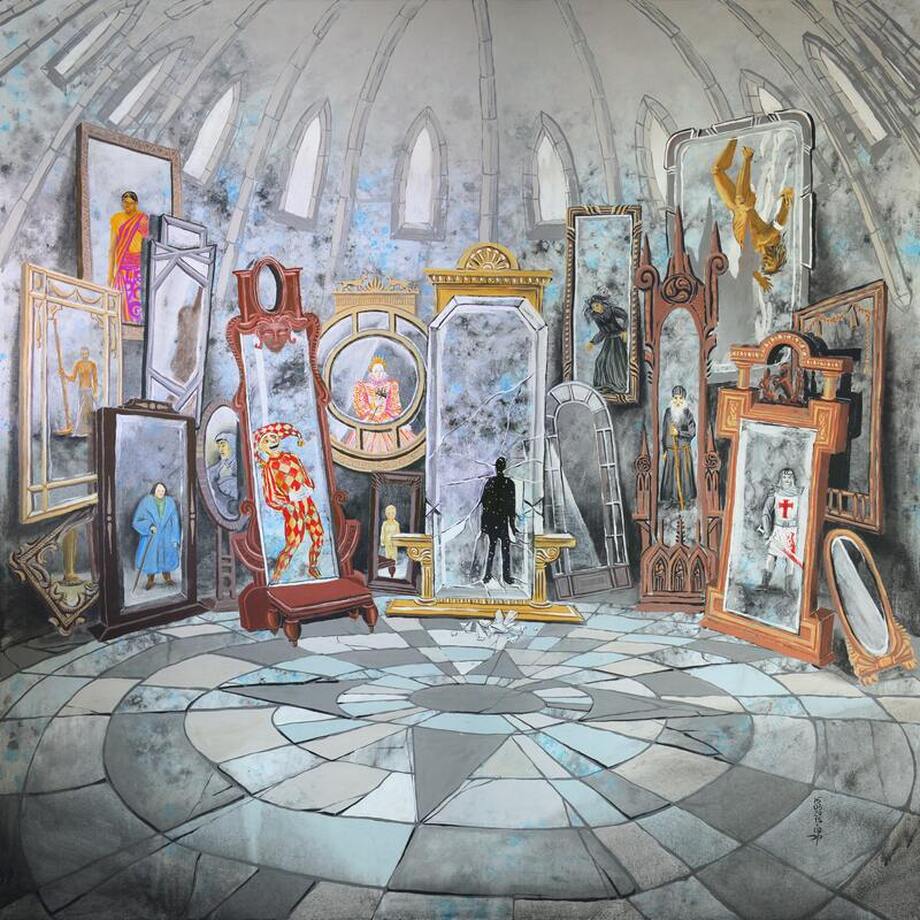

Photo by Дмитрий Хрусталев-Григорьев on Unsplash

| one_life_many_lives_an_internal_hindu_ch.pdf | |

| File Size: | 226 kb |

| File Type: | |

| god_creativity_monism_and_pluralism_the__1_.pdf | |

| File Size: | 325 kb |

| File Type: | |

Affinities between Hinduism and Process Philosophy

Indeed, I suspect the affinities of process thought to Hinduism to be greater than its affinities with Christianity, at least as conventionally conceived.

Hindu Process Theology

As in the translation of languages, the translation of concepts from one system to another is rarely, if ever, a simple matter of one-to-one correlation. Inevitably, taking an idea from one system and correlating it with an idea from another, especially when the two systems of thought have arisen in very different cultural and linguistic settings, involves distortion. But rather than being frustrated by this fact, or seeing it as a barrier to showing the mutual relevance of process thought and Hinduism, I think one should instead see it, in the spirit of Whitehead, as an occasion for ‘creative transformation’–as a ‘creative distortion’–in which a third, new, ‘hybrid’ system can arise: a Hindu process theology, which sheds new light on both Hinduism and process thought at the same time.

The argument

I shall argue that process thought can be of benefit to Hinduism are:

1. To aid in the recovery of the concept of māyā as ‘creativity,’ rather than as ‘illusion,’ as it has often been translated in academic scholarship.

2. To aid in the articulation of the doctrine of the jīva, or soul, by means of the process affirmation of ontological monism with structural dualism.

3. To aid in the articulation of the religious pluralism of the Ramakrishna tradition with the process concept of the three ultimate realities.

I will argue, furthermore, that Hinduism can also benefit process thought, by shedding light on specific process concepts and concerns. Specifically:

1. Hinduism sheds light on the process understanding of soul development by affirming that souls have, like God and the world, always existed.

2. The Hindu emphasis on the fundamental unity of existence complements the emphasis of process thought on change and difference.

3. Hinduism demonstrates that a non-omnipotent deity can be worshiped with intensity and devotion, contrary to the claims of classical theology

Jeffery Long as Hindu

I believe in reincarnation, meditate daily, and perform pūjā to Hindu deities. I formally became a Hindu through a ceremony performed by a priest of the Ārya Samāj. I have a Hindu wife whom I married in a Hindu ceremony. I have a guru who is a member of an ancient order of Hindu monks. And, on one occasion, I was the officiating priest at a Hindu wedding. If I am not a Hindu, then, I ask, who is? The purpose of all this self-disclosure is to allay the concerns of any Hindus who may be alarmed at the prospect of a Westerner presuming to do Hindu theology–to whom even the word theology sounds suspiciously Christian–and claiming that Hindu traditions might have something to learn from something as Western- and Christiansounding as ‘process theology.’ I am therefore stating at the outset that this theological project is carried out in the service of Hinduism, by a thinker who identifies himself as Hindu, and not by a covert Christian missionary engaged in ‘acculturation’ in order to facilitate the conversion of Hindus to Christianity–a concern of many Hindus today

Brahman, Creativity and God

What is Brahman? Brahman could be defined as existence itself, the totality of Being. Also called ‘the Real’ (sat), Brahman is coextensive with reality as such. It is that which is real pre-eminently, and from which the existence of all other entities is derivative and in which they participate. It is that, by knowing which, all things are known.16 It is also the ultimate object of religious aspiration, of the ancient Upaniṣadic prayer, “Lead me from the unreal to the real, from darkness to light, from death to immortality.” It is eternal. “It is immortal; it is Brahman; it is the Whole.” As a word, Brahman literally means “the expansive” or “that which makes things great.”

At this point, a process thinker might recall Whitehead’s characterization of the ultimate reality as ‘creativity,’ to which I would argue Brahman corresponds. On Whitehead’s account, this ultimate reality “is actual in virtue of its accidents. It is only then capable of characterization through its accidental embodiments, and apart from these accidents it is devoid of actuality.” It is an ultimate principle that takes on a concrete reality as the actual entities making up the world. Whitehead goes on to say that, “In monistic philosophies, Spinoza’s or absolute idealism, this ultimate is God, who is also equivalently termed ‘The Absolute.’” This is quite similar to Brahman’s being the ultimate object of religious aspiration. But, Whitehead continues, “In such monistic schemes, the ultimate is illegitimately allowed a final, ‘eminent’ reality, beyond that ascribed to any of its accidents.." If anything, this would seem to point to a radical disjuncture between Vedānta and process thought; for what is Brahman but a supremely real reality, from which all other things are held to be derivative, and which is regarded as God? Is Vedānta not another form of monistic absolute idealism?

But we must recall here the various systems of interpretation that exist within the broad framework of Vedānta, as well as Whitehead’s own distinction between the ultimate reality which he terms ‘creativity’ and God. For Whitehead, God is not creativity and creativity is not God. Creativity is, again, “an ultimate which is actual in virtue of its accidents.” It is actual inasmuch as it is manifested in and as the realm of time and space. But God is creativity’s “primordial, non-temporal accident.” God is, for Whitehead, derivative from creativity, the supreme embodiment of creativity, “a stable actuality whose mutual implication with the remainder of things secures an inevitable trend towards order.”

God as Isvara

The Vedāntic concepts that correlate with the process ideas of God and world are Īśvara and Jagat. Īśvara, ‘the Lord’–usually visualized as either Viṣṇu or Śiva– plays much the same role in Vedānta that God does in process thought: as the supreme actuality that coordinates all other actual entities and constitutes them into a coherent universe. The jagat, or world, correlates with the process idea of the world made up of actual entities. Interestingly, the literal meaning of jagat is ‘flow’ or ‘process.’ So the world is understood in Hinduism as a flow of temporary events, in a state of constant flux, just as it is in process thought. Similarly, Īśvara and the jagat have both always existed. Although the entities that make up the jagat are individually of a momentary and impermanent character, the collective flow that they make up is ongoing. God is not the creator of the world ex nihilo, but co-exists with it perpetually in a state of mutual interaction, just like in process thought.

Body and Soul

Turning now to ways in which Hinduism can be of benefit to process thought, the first of these is with regard to the topic, discussed earlier, of the relationship of soul and body. We have already seen that process thought elucidates the Hindu view of the distinction between soul and body with its idea of the different types of structure that are formed by actual entities. As Griffin argues, the Hindu doctrine of rebirth–or reincarnation–which I have mentioned earlier, but have not yet discussed in any depth, is wholly compatible with process thought. For a Hindu process thinker, an important contribution of Hinduism to process thought regards the origin of souls–that, like God and the world, they simply have always existed–and that the reasons for their associating themselves with bodies, for rebirth, have to do with lessons they need to learn, with their search for that state of freedom from the conditioning of the past–from karma–that is their ultimate goal.

No Omnipotent Deity: No Problem! The God of Dvaita Vedānta, and of Hindu theism in general, is omniscient in the sense of knowing all actuality and all possibility, and is also supremely benevolent, being the pre-eminent locus of all good qualities (guṇāśraya). But, while being supremely powerful, God is not understood in Dvaita Vedānta as being omnipotent in the sense to which process thinkers typically object. Mādhva is at one with process thought in affirming that God co-exists in the world with numerous other free beings–the jīvas, or living souls. Just as in process thought, the freedom of non-divine actual entities is not an illusion, or a gift that has been shared with them by an inherently omnipotent being, with which all the power ultimately resides. Actual entities simply are free. Because of its affirmation of divine non-omnipotence, Dvaita scholar Deepak Sarma describes this system as a ‘mitigated monotheism.’...The greatest single obstacle to the widespread acceptance of process thought in the West has been precisely the idea of God as non-omnipotent, an idea that many believe renders God unworthy of worship. Yet this conception of God does not prevent Hindus from experiencing intense theistic devotion.

Only the surface

Clearly, I have only begun to scratch the surface of the potential interactions of process thought and Hinduism in this essay. Further development of Hindu process theologies will no doubt reveal even more points of contact, as well as potential areas of creative tension, between process thought and the rich, vast, and complex family of traditions that go by the name of Hinduism