- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

The Obtrusion of Moral Sentiment

Few lines written by Coleridge are more familiar than those near the end of the Rime of the Ancient Mariner:

He prayeth best, who loveth best

All things, both great and small;

For the dear God who loveth us,

He made and loveth all.

And perhaps no lines in his poetry have served as the starting point of so much critical discussion. For the "moral" of the Ancient Mariner has been attacked, defended, denied, affirmed many times since Mrs. Barbauld first raised the question and Coleridge answered her.'

In his Table Talk for May 31, 1830, the poet says: "Mrs. Barbauld once told me that she admired the Ancient Mariner very much, but that there were two faults in it-it was improbable and had no moral. As for the probability, I owned that that might admit some question; but as to the want of a moral, I told her that in my own judgment the poem had too much; and that the only, or chief fault, if I might say so, was the obtrusion of the moral sentiment so openly on the reader as a principle or cause of action in a work of such pure imagination. It ought to have had no more moral than the Arabian Nights' tale of the merchant's sitting down to eat dates by the side of a well, and throwing the shells aside, and lo! a genie starts up, and says he must kill the aforesaid merchant, because one of the date shells had, it seems, put out the eye of the genie's son,

Nitchie, Elizabeth. “The Moral of the Ancient Mariner Reconsidered.” PMLA, vol. 48, no. 3, 1933, pp. 867–76. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/458348. Accessed 4 Feb. 2024.

He prayeth best, who loveth best

All things, both great and small;

For the dear God who loveth us,

He made and loveth all.

And perhaps no lines in his poetry have served as the starting point of so much critical discussion. For the "moral" of the Ancient Mariner has been attacked, defended, denied, affirmed many times since Mrs. Barbauld first raised the question and Coleridge answered her.'

In his Table Talk for May 31, 1830, the poet says: "Mrs. Barbauld once told me that she admired the Ancient Mariner very much, but that there were two faults in it-it was improbable and had no moral. As for the probability, I owned that that might admit some question; but as to the want of a moral, I told her that in my own judgment the poem had too much; and that the only, or chief fault, if I might say so, was the obtrusion of the moral sentiment so openly on the reader as a principle or cause of action in a work of such pure imagination. It ought to have had no more moral than the Arabian Nights' tale of the merchant's sitting down to eat dates by the side of a well, and throwing the shells aside, and lo! a genie starts up, and says he must kill the aforesaid merchant, because one of the date shells had, it seems, put out the eye of the genie's son,

Nitchie, Elizabeth. “The Moral of the Ancient Mariner Reconsidered.” PMLA, vol. 48, no. 3, 1933, pp. 867–76. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/458348. Accessed 4 Feb. 2024.

Obtrusion

Obtrusion is the act of imposing or forcing something, often unwanted or intrusive, upon a person, situation, or environment. It involves making something conspicuous, noticeable, or prominent in a way that it disrupts or interferes with the natural flow or order of things. The obtrusion of moral sentiment" clouds life with a sense of obligation and righteousness, often at the expense of unfettered imagination or pure attention. Or the simple joy of being alive.

- Jay McDaniel

- Jay McDaniel

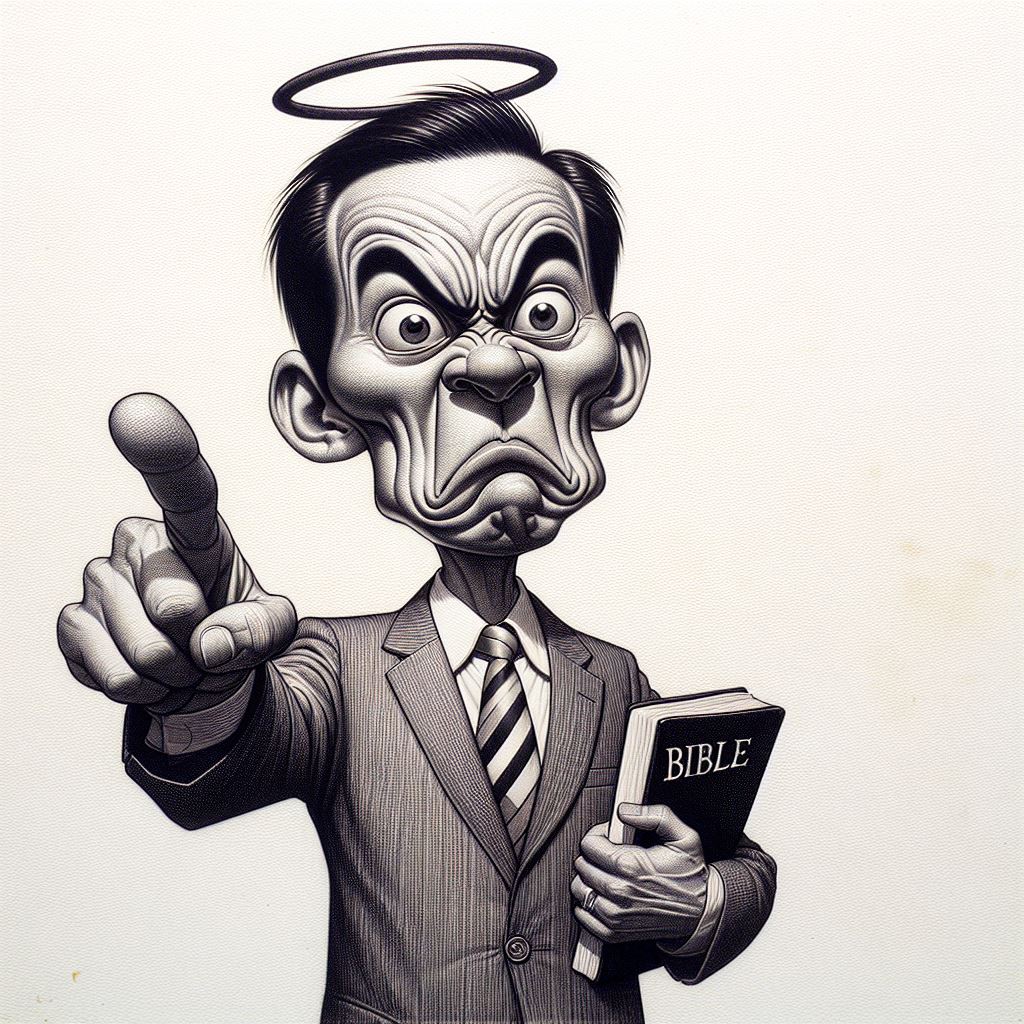

You sure say "Ought" a Lot!

I remember giving a talk in an adult Sunday School class on theology. I think the talk was about God and how we ought to think of God as all-loving but not all-controlling.

During the talk, a man raised his hand and commented, 'You sure say 'ought' and 'should' a lot.' He was talking not just about the content of what I said, but the spirit in which I said it. There was a hidden or not-so-hidden sanctimony in it.

He was right. I was sanctimonious. Somehow, I had it in my mind that theology, all of it, was supposed to be about ethics: about how we 'ought' to live in the world if we are responsive to God's call and if we are loving in our relationship with others. I was all about obligation, albeit of a process kind. Yet, I also had and still have other aspects of my life that are not about ethics at all. I love music, I love dogs, I love a good story even when there is no 'moral' to it, I love life. When I hear a good story or listen to music, I can enjoy them without, to quote Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 'the obtrusion of moral sentiment.'

My friend's comment made me realize that moral sentiment is not the whole of life, and we do life a disservice, as well as God, when our consciousness is overly steeped in the 'ought' at the expense of the 'is' and 'might be.' We become insufferably 'preachy' in the worst sense of the word. This is true of liberals and conservatives and many in between. I suspect I'm being a little preachy in saying what I've just said.

Here's to those many moments in life when moral sentiment does not obtrude. May our theologies, and our ways of living in the world, be faithful to them.

- Jay McDaniel

Why Henry Gave Up on Theology

Once upon a time in a quiet, leafy town nestled between rolling hills, there lived a gentle soul named Henry. He had always been drawn to the beauty of the world, not just as a mere aesthetic, but as a spiritual connection to what he believed was God's body. The way sunlight filtered through leaves, the delicate dance of raindrops on petals, and the symphony of birdsong at dawn – all these wonders whispered to him the divine presence in every corner of existence.

One day, while exploring the dusty shelves of the local bookstore, Henry stumbled upon a thick tome with the title "Theology and the Beauty of the World." The book's cover, adorned with an intricate mosaic of nature's wonders, captivated him instantly. He hoped that within its pages, he would find a deeper understanding of the world as a reflection of God's grandeur.

With great anticipation, Henry took the book home and settled into his cozy armchair by the fireplace. The scent of burning wood filled the air as he gently opened the book and began to read. He was immediately struck by the eloquent prose and the author's deep reverence for the divine.

However, as Henry delved deeper into the text, he began to sense a shift in its tone. The book, he discovered, was less about the awe-inspiring beauty of the world and more about the moral obligations one should follow as a devout believer. The author's words became increasingly focused on rules, doctrine, and the strict adherence to religious principles.

Henry's heart sank as he realized that this theology book, despite its promising title, had veered into a realm of strict moralism. It seemed to dwell more on what was permissible and what was forbidden, rather than celebrating the world as God's magnificent creation. The beauty he had sought to explore was overshadowed by a rigid set of guidelines, leaving him feeling trapped and disillusioned.

As the days passed, Henry continued to read the book, hoping that it would eventually reveal the connection between God's beauty and the moral teachings. He yearned for the author to bridge the gap between the spiritual and the practical, but alas, his hopes remained unfulfilled.

One evening, after finishing the book, Henry sat by his open window, gazing at the serene moonlit landscape outside. He felt a deep sense of disappointment and frustration. The world's beauty, which he had once perceived as a testament to God's splendor, now seemed burdened by the weight of morality.

With a heavy heart, he decided to put the book aside, realizing that the true beauty of the world could not be confined to the pages of any tome. It was found in the delicate petals of a blooming flower, the laughter of children at play, and the harmony of nature's rhythms. Henry understood that theology, while essential, should not obscure the simple yet profound beauty of existence.

And so, he continued to explore the world with open eyes and an open heart, finding God's presence not in strict moral codes but in the unending tapestry of the natural world, where beauty and wonder danced freely and uninhibited.

- AI Generated

One day, while exploring the dusty shelves of the local bookstore, Henry stumbled upon a thick tome with the title "Theology and the Beauty of the World." The book's cover, adorned with an intricate mosaic of nature's wonders, captivated him instantly. He hoped that within its pages, he would find a deeper understanding of the world as a reflection of God's grandeur.

With great anticipation, Henry took the book home and settled into his cozy armchair by the fireplace. The scent of burning wood filled the air as he gently opened the book and began to read. He was immediately struck by the eloquent prose and the author's deep reverence for the divine.

However, as Henry delved deeper into the text, he began to sense a shift in its tone. The book, he discovered, was less about the awe-inspiring beauty of the world and more about the moral obligations one should follow as a devout believer. The author's words became increasingly focused on rules, doctrine, and the strict adherence to religious principles.

Henry's heart sank as he realized that this theology book, despite its promising title, had veered into a realm of strict moralism. It seemed to dwell more on what was permissible and what was forbidden, rather than celebrating the world as God's magnificent creation. The beauty he had sought to explore was overshadowed by a rigid set of guidelines, leaving him feeling trapped and disillusioned.

As the days passed, Henry continued to read the book, hoping that it would eventually reveal the connection between God's beauty and the moral teachings. He yearned for the author to bridge the gap between the spiritual and the practical, but alas, his hopes remained unfulfilled.

One evening, after finishing the book, Henry sat by his open window, gazing at the serene moonlit landscape outside. He felt a deep sense of disappointment and frustration. The world's beauty, which he had once perceived as a testament to God's splendor, now seemed burdened by the weight of morality.

With a heavy heart, he decided to put the book aside, realizing that the true beauty of the world could not be confined to the pages of any tome. It was found in the delicate petals of a blooming flower, the laughter of children at play, and the harmony of nature's rhythms. Henry understood that theology, while essential, should not obscure the simple yet profound beauty of existence.

And so, he continued to explore the world with open eyes and an open heart, finding God's presence not in strict moral codes but in the unending tapestry of the natural world, where beauty and wonder danced freely and uninhibited.

- AI Generated