God the Deep Remembering

God remembers each life and story,

with a tender care that nothing be lost,

weaving them into a universal feeling

that includes all lives and stories.

as if they (the lives and stories)

were born today. Always today.

God is these lives and stories

and the loving memory of them.

springboards for reflection

offered by Jay McDaniel, 5/14/2021

The wisdom of subjective aim prehends every actuality for what it can be in such a perfected system— its sufferings, its sorrows, its failures, its triumphs, its immediacies of joy— woven by rightness of feeling into the harmony of the universal feeling, which is always immediate, always many, always one, always with novel advance, moving onward and never perishing. The revolts of destructive evil, purely self-regarding, are dismissed into their triviality of merely individual facts; and yet the good they did achieve in individual joy, in individual sorrow, in the introduction of needed contrast, is yet saved by its relation to the completed whole. The image— and it is but an image— the image under which this operative growth of God's nature is best conceived, is that of a tender care that nothing be lost. (Whitehead, Alfred North. Process and Reality (Gifford Lectures Delivered in the University of Edinburgh During the Session 1927-28) (p. 346)

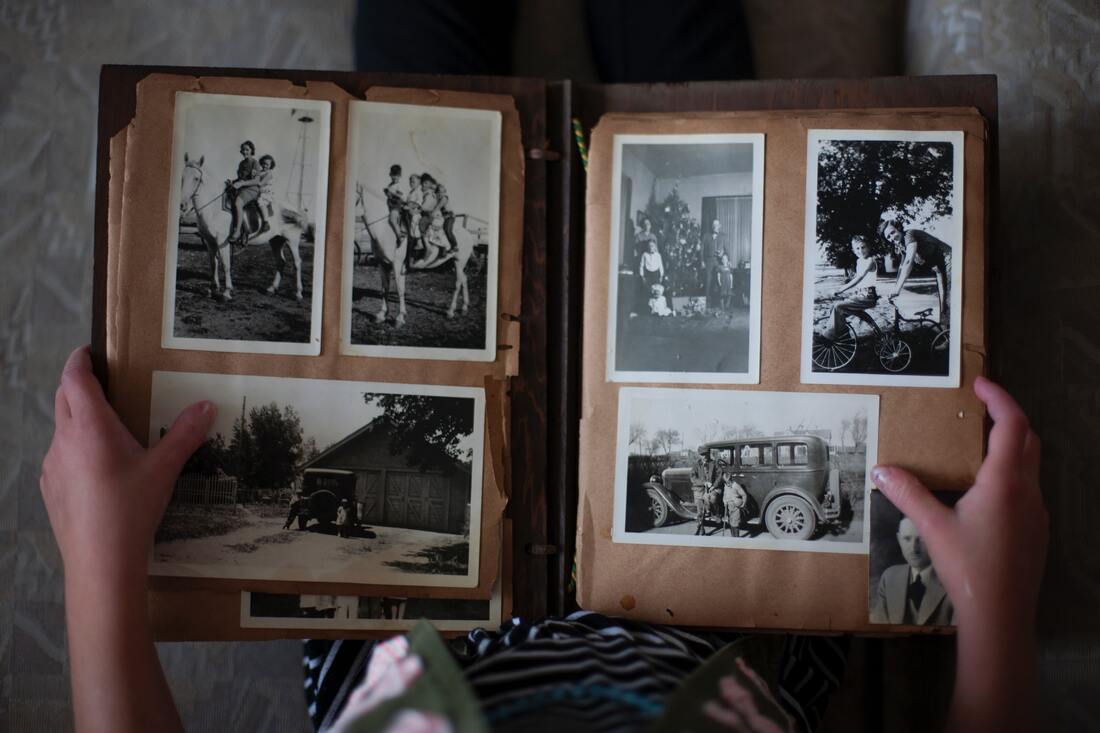

God is a living scrapbook. The contents of God's life are not photographs but feelings: that is, the feelings that each living being on earth or any other dimension of existence suffers, enjoys, or otherwise undergoes: sufferings, sorrows, failures, triumphs, immediacies of joy. Once these feelings happen, they become part of God's memory, who receives them with a tender care that nothing be lost, weaving them into a completed whole.

In the case of human beings, these feelings form a story - the story of a person's life. Each person has a story and each story becomes part of God's life. The end of a person's story is not how that person thinks of his or her life; it is how that person's story is transmuted by God into a meaning and beauty the person may not know. And this end may not have an ending. Or, to say the same things, its ending may be ongoing. We do not and need not know the meaning of our lives. We need only have faith that there is a meaning beyond our imaginations. Only God knows and loves the scrapbook. It is the glory of God, understood not as power, however sublime, but as tender care.

- Jay McDaniel

In the case of human beings, these feelings form a story - the story of a person's life. Each person has a story and each story becomes part of God's life. The end of a person's story is not how that person thinks of his or her life; it is how that person's story is transmuted by God into a meaning and beauty the person may not know. And this end may not have an ending. Or, to say the same things, its ending may be ongoing. We do not and need not know the meaning of our lives. We need only have faith that there is a meaning beyond our imaginations. Only God knows and loves the scrapbook. It is the glory of God, understood not as power, however sublime, but as tender care.

- Jay McDaniel

The objective immortality of the past as embodied in the palpable presence of what is old (AN Whitehead); both revealing and concealing its history (Martin Heidegger); and revealing something of its own energy, its own aliveness (AN Whitehead); which can be captured but never exhausted in a photograph (Thomas Oord); and which functions as a means by which God's uncontrolling guidance (Thomas Oord and AN Whitehead) becomes available for all who wonder. The stove is not simply an object in the world, reducible to mere data. It is what Whitehead calls a lure for feeling: a proposition. It, too, belongs to the Republic of Stories. Our task is to listen, wonder, and remind ourselves, perpetually, that the universe is not a collection of objects but rather a communion of subjects (Thomas Berry) enfolded within the Deep Remembering whom we name "God." God is the living repository for all the stories and for those who tell them (AN Whitehead). They are cared for, in Whitehead's words, with "a tender care that nothing be lost." Old stoves are among the best of storytellers, both in what they reveal and what they conceal. Rest quietly in their presence.

-- Jay McDaniel

-- Jay McDaniel

human stories - one life at a time

|

WE ARE IN THE MIDST OF SEISMIC CULTURAL CHANGE. In the old paradigm, priorities are shaped by a mechanistic worldview that privileges whatever can be numbered, measured, and weighed; human beings are pressured to adapt to the terms set by their own creations. Macroeconomics, geopolitics, and capital are glorified. . . . In the new paradigm, culture is given its true value. The movements of money and armies may receive close attention from politicians and media voices, but at ground-level, we care most about human stories, one life at a time.” -- Arlene Goldbard, The Culture of Possibility: Art, Artists, and the Future

|

GROWING UP THROUGH THE CRACKS of the broken worldview we call modernity are verdant shoots we call stories—human stories built of words and images and feelings and connected threads of subjective experience. We see them everywhere, not only in film and literature, but in the daily lives of regular people telling their own stories about where they come from and what makes them happy or sad, about people they love and animals that make them laugh or weep. About what makes life meaningful.

-- Patricia Adams Farmer, A Whole Universe of Stories |

God as Deep Memory

Perhaps there’s always a little something sad about the decay side of life: the side which passes away, never to return in its subjective immediacy (Whitehead). Those of us who celebrate “embodiment” – and it’s quite fashionable in the anti-platonic spirit of contemporary times – best remember that part of being embodied is to partake of the decay side. We need not pretend that all death is good, even though some may be beautiful. A life well-lived must come to grips with impermanence (Buddhism). We are all stoves.

Sunset

Imagine that there is “a unifying source of life and connection that links the whole universe and everything that is in the universe” (Artson). Let “God” be one of its names and, along with Rabbi Bradley Artson, think of this source on the analogy of a sunset:

Like a glorious sunset, it can be experienced even without being understood. We are often able to experience a relationship with something/someone we cannot completely describe. If that is true, and I believe that it is, then our descriptions of what we call God is always more than our description, and always also beyond our description. [1]

Recognize as well that the source can be imagined as a force, or a person, or both.

And it should not be a surprise, in a universe that emerges as forces (gravity, the tides, etc.), and as minds (octopi, bees, birds, people) that we would yearn to apply both descriptors to the source of all. [1]

Use whatever metaphors you need to help orient your mind and heart to the source. And use lots of them.

When we encounter something that cannot be contained in our verbal descriptions or mental compartments, the best approach is to multiply incomplete metaphors, each illuminating one aspect of a totality beyond our grasp. In Jewish tradition, God is described as “monarch,” “shepherd,” “fountain of life,” “life of the universe,” “parent,” “artist,” and many other terms that combine to help us create an emotional silhouette of this cosmic mind, this oneness, this source of creativity and goodness.

Don't let anybody tell you there's only one metaphor for God.

Can and Can't

Can this source reverse the decay side of life? Can it un-happen what has happened? Can it eliminate our need, as human beings, to make peace with impermanence?

Thomas Oord has written a book called God Can’t in which he talks about the things God can’t do. Tom has in mind the many evils that God cannot prevent, even as God is doing all that God can do. I've done a review of his book: Leaning out for Love.

I’m with Tom. Some people believe in a God who has the power to manipulate the world for good, but chooses not to use such powers. Along with Tom and his mentor, John Cobb, I believe in a God who is doing all that God can do, all the time, for the sake of what is good and true and beautiful. God is like the sunset -- very, very beautiful -- everywhere at once -- doing all that it can do, but without leaving behind unused powers.

Old but New

So how might this God of boundless yet uncontrolling love help us deal with the decay side of life. Here I find wisdom in Oord's photograph offered above: the old stove. It symbolizes for me, not only the reality if impermanence which is part of each and every embodies being, but also what the philosopher Whitehead calls the objective immortality of the past.

The objective immortality of the past is the palpable presence of what is old; both revealing and concealing its history (Martin Heidegger); and revealing something of its own energy, its own aliveness (AN Whitehead) along the way. The past is not merely dead; it is also living in a new way, devoid of the immediacy it once had, but energetic nevertheless. Thus can become, for us, a source of wonder. The stove is not simply an object in the world, reducible to mere data. It is what Whitehead calls a lure for feeling: a proposition. It, too, belongs to the Republic of Stories.

Our task is to listen, wonder, and remind ourselves, perpetually, that the universe is not a collection of objects but rather a communion of subjects (Thomas Berry) enfolded within the Deep Remembering. God is the living repository for all the stories and for those who tell them. They are cared for, in Whitehead's words, with "a tender care that nothing be lost."

Old stoves are among the best of storytellers, both in what they reveal and what they conceal. We can quietly in their presence.

And we can also wonder, perhaps hope, that their stories are retained in an even more complete way in the ongoing love of the "unifying source of life and connection that links the whole universe and everything that is in the universe."

Whitehead speaks of this ongoing love as the consequent nature of God. It is that side of God in which all things are present as part of God's body. God's body is the universe itself as enfolded into God's life. Imagine that as we see the sunset we are simultaneously included in its beauty. We partake of it, even without our understanding how this occurs.

We really do not know that the stove looks like in God's memory, or what we look like either. But we can have faith that no stories are lost, and that all are part of larger vision belonging to the Sunset. All partake of new life in God even amid, and perhaps even because of, the decay. Does this mean that we old stoves -- and our loved ones -- enjoy a continuing journey after death. Many process theologians believe so; and I am among them. But my faith is in the Sunset and its transformative power. That's enough and, truth be told, plenty.

-- Jay McDaniel

Sunset

Imagine that there is “a unifying source of life and connection that links the whole universe and everything that is in the universe” (Artson). Let “God” be one of its names and, along with Rabbi Bradley Artson, think of this source on the analogy of a sunset:

Like a glorious sunset, it can be experienced even without being understood. We are often able to experience a relationship with something/someone we cannot completely describe. If that is true, and I believe that it is, then our descriptions of what we call God is always more than our description, and always also beyond our description. [1]

Recognize as well that the source can be imagined as a force, or a person, or both.

And it should not be a surprise, in a universe that emerges as forces (gravity, the tides, etc.), and as minds (octopi, bees, birds, people) that we would yearn to apply both descriptors to the source of all. [1]

Use whatever metaphors you need to help orient your mind and heart to the source. And use lots of them.

When we encounter something that cannot be contained in our verbal descriptions or mental compartments, the best approach is to multiply incomplete metaphors, each illuminating one aspect of a totality beyond our grasp. In Jewish tradition, God is described as “monarch,” “shepherd,” “fountain of life,” “life of the universe,” “parent,” “artist,” and many other terms that combine to help us create an emotional silhouette of this cosmic mind, this oneness, this source of creativity and goodness.

Don't let anybody tell you there's only one metaphor for God.

Can and Can't

Can this source reverse the decay side of life? Can it un-happen what has happened? Can it eliminate our need, as human beings, to make peace with impermanence?

Thomas Oord has written a book called God Can’t in which he talks about the things God can’t do. Tom has in mind the many evils that God cannot prevent, even as God is doing all that God can do. I've done a review of his book: Leaning out for Love.

I’m with Tom. Some people believe in a God who has the power to manipulate the world for good, but chooses not to use such powers. Along with Tom and his mentor, John Cobb, I believe in a God who is doing all that God can do, all the time, for the sake of what is good and true and beautiful. God is like the sunset -- very, very beautiful -- everywhere at once -- doing all that it can do, but without leaving behind unused powers.

Old but New

So how might this God of boundless yet uncontrolling love help us deal with the decay side of life. Here I find wisdom in Oord's photograph offered above: the old stove. It symbolizes for me, not only the reality if impermanence which is part of each and every embodies being, but also what the philosopher Whitehead calls the objective immortality of the past.

The objective immortality of the past is the palpable presence of what is old; both revealing and concealing its history (Martin Heidegger); and revealing something of its own energy, its own aliveness (AN Whitehead) along the way. The past is not merely dead; it is also living in a new way, devoid of the immediacy it once had, but energetic nevertheless. Thus can become, for us, a source of wonder. The stove is not simply an object in the world, reducible to mere data. It is what Whitehead calls a lure for feeling: a proposition. It, too, belongs to the Republic of Stories.

Our task is to listen, wonder, and remind ourselves, perpetually, that the universe is not a collection of objects but rather a communion of subjects (Thomas Berry) enfolded within the Deep Remembering. God is the living repository for all the stories and for those who tell them. They are cared for, in Whitehead's words, with "a tender care that nothing be lost."

Old stoves are among the best of storytellers, both in what they reveal and what they conceal. We can quietly in their presence.

And we can also wonder, perhaps hope, that their stories are retained in an even more complete way in the ongoing love of the "unifying source of life and connection that links the whole universe and everything that is in the universe."

Whitehead speaks of this ongoing love as the consequent nature of God. It is that side of God in which all things are present as part of God's body. God's body is the universe itself as enfolded into God's life. Imagine that as we see the sunset we are simultaneously included in its beauty. We partake of it, even without our understanding how this occurs.

We really do not know that the stove looks like in God's memory, or what we look like either. But we can have faith that no stories are lost, and that all are part of larger vision belonging to the Sunset. All partake of new life in God even amid, and perhaps even because of, the decay. Does this mean that we old stoves -- and our loved ones -- enjoy a continuing journey after death. Many process theologians believe so; and I am among them. But my faith is in the Sunset and its transformative power. That's enough and, truth be told, plenty.

-- Jay McDaniel

Three Kinds of Life After Death

Subjective Immortality in a Continuing Journey after Death

Recently I saw a photograph of my great grandmother. It was the first time I had seen it, and, to my knowledge, it is the only photograph of its kind. I wondered where she is now.

It is possible that she is on a continuing journey extending beyond her death, and that her journey is unfolding in other dimensions of existence. After all, we live in a multi-dimensional universe; and there is no reason to think that three-dimensional space as we experience it is the whole of things. She may exist in a fifth dimension, or a thirty-fourth dimension.

It is also possible that one of the dimensions is very close to the loving heart of the universe, to God, and that her journey unfolds near the light of God. Perhaps in this sphere she is also reunited with her loved ones in blessed ways, and with all others as well. This would be heaven.

In any case my hope is that she is finding, or has found, the peace and joy that I am sure she sought on earth. My hope is that she is enjoying what process theologians speak of as “subjective immortality.”

Objective Immortality on Earth

I have friends who don’t believe in subjective immortality and who propose an alternative way of thinking about life after death. They say that she was made of energy, as are all living beings; and that the energy of her life still exists in some way on earth. They think of her body as made of energy and her emotions and thoughts. Quoting the law of energy conservation, they say: “Energy is neither created nor destroyed.”

In effect they are saying that something about my great grandmother exists even today, not in heaven but on earth as the energy of her life has been converted into other, newer forms. I am wondering about the energy of her own past form, prior to its being transformed into newer forms. Does her own past form still exist in some way, or has it been extinguished? I have not gotten a clear answer to this, but I certainly understand their intentions. They want to say my great grandmother did not simply die. Something of her continues even today. They are affirming what process theologians call “objective immortality on earth.” I support this idea.

Objective Immortality in God

But it is not really the energy of my great-great grandmother that I am wondering about. It is her concrete, specific experiences: what she felt as she was standing over a stove, how she responded to the death of her first child, what her relationship with her husband was, what she hoped for. It is her life, as lived from the inside, day by day and moment by moment, on her terms. It is her story.

Does her story still exist? Even if it does not continue on its own terms; is it remembered? Does it matter? Does it count? Given that her story in its specifics and on its own terms has been forgotten by everyone on earth, is it nevertheless remembered, and maybe even loved, by God? This would be what process theologians call “objective immortality in God.” I support this idea, too.

- Jay McDaniel