Leaning out for Love

A Reflection on Thomas Oord's God Can't

There are heroes in the seaweed, there are children in the morning.

They are leaning out for love and they wil lean that way forever.

-- Leonard Cohen, Suzanne

by Jay McDaniel 1/15/2019

A Book for Love-Leaners

I think Suzanne might understand the motivation of Thomas Oord's book. I'm talking about the Suzanne of Leonard Cohen's song, as sung by Judy Collins. The one who sees heroes in the seaweed and children in the morning, and who is leaning out for love and will lean that way forever.

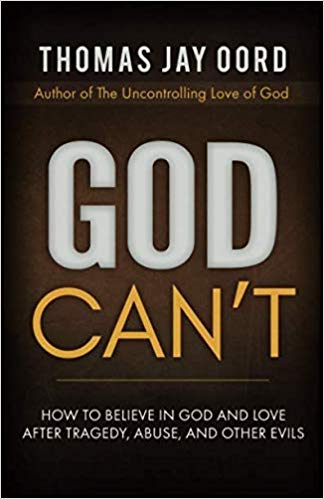

Thomas Oord's God Can't is leaning out for love, too. Don't let its title deceive you. He wants to talk about a Love that is at the center of the universe whom he names God. But he wants you to understand that there are some things that happen in the world that God can't control, because God is love. He wants you to be able to love the Love and maybe even worship it, albeit out of affection and attraction, not fear of punishment. He thinks the Love is a person and not just a force. He thinks this Love was revealed in, but not exhausted by, a young Jew from Nazareth whose healing ministry was and still is a beacon of light for the world. In God Can't Thomas Oord wants to speak to your heart.

If you are a theologian you might not recognize Oord's pastoral aim at first. You might think Thomas Oord's God Can't is all about a battle royale between those who hold (what he takes to be) right ways of thinking about God and those who hold (what he takes to be) wrong ways of thinking about God, given the problem of evil in the world. By evil he means pain and tragedy from which there is no compensating good. Oord is, after all, an evangelical Christian, trained in traditions of theological debate where writers (mostly male) speak with authoritative voices in terms of right view and wrong views. They like to "argue" with each other. They draw lines and defend "positions." They prize "clarity" as if clarity were a god in its own right. Often they speak in what the novelist Ursula K. Le Guin calls a male, authoritarian voice -- declarative and argumentative -- even if they happen to be women. These theologians are not as good at telling stories or accepting life's ambiguities. They can't see heroes in the seaweed.

God Can't is less argumentative and more pastoral. It has lots and lots and lots of stories. It is written most specifically for a Christian whose heart leans out toward love, but who was taught, perhaps at an early age, that the universe is overseen by an all-powerful God who can do anything "he" wants. This Christian is troubled and perhaps tormented by the fact that there is so much tragedy in the world and that, in fact, God doesn't really do anything about it. God seems distant and cold, like a king on a throne. Or perhaps parental, but more like a strict and flattery-preoccupied father than a loving Abba. The Christian begins to wonder if God is really loving at all. Or perhaps even exists at all. The Christian leans out for love, but isn't sure God can be leaned on. Thomas Oord wants to give this Christian something to lean on.

Leaning out toward Love

But let's back up. There are many people in the world whose hearts lean out toward love, and they are not just Christians. Some are religiously affiliated; some are not; and many are somewhere in between. Together they form an extended family of love-leaners. One my favorite theologians, Rabbi Bradley Artson, is a Jewish love-leaner; another, Shoryu Bradley, is a Buddhist love-leaner; still another, Farhan Shah, is a Muslim love-leaner. In the house of love-leaners there are many rooms. My mother, Virginia McDaniel, was a love-leaner, too. I remember asking her one time, when I was about six years old, who Jesus was, and she said, "He is someone who is always holding your hand even when you don't know it."

My mother captured what love-leaners feel. They -- we -- feel that somehow, some way, there's something in the universe, deeply compassionate, that is always holding everyone's hands, even when they don't know it. Or at least we want to believe this. We want to believe that love is more ultimate than anything else. We do not ask that love be all-powerful, but we do ask that love be more fundamental than the violence and the sadness. We want to have faith in love.

Infant Baptism

How does our faith in love emerge? There may or may not be some gene in our bodies which inclines us to lean toward love from the very outset of life. I suspect there is, but I'll leave that to the biologists.

One thing is clear. The impulse toward love-leaning is connected to the impulse toward trust in a nurturing environment, and the latter impulse, whether activated or not, is part of our lives from a very early age. Biologically and psychologically, indeed spiritually, we need to trust in nurturance from a very early age. We are born with what Muslims call fitra: a disposition to sense, and feel protected by, a unity beyond our ken, of which we are a part.

For most of us, the trust is satisfied at an early age, with milk. As soon as we survive the trial of birth, and rest in our mother's arms, we begin to sense the possibility of trusting in a nurturing environment.

Not much later, in early childhood if not in infancy, this trust can be nurtured by our families, if we are very lucky. If we had loving families, where we ourselves felt loved, the parental and familial love we received as children became, for us, a window into something deep and wonderful: a kind of supportive love that is more than even our parents. This feeling of a wider love is our first intuition that God is Love. It does not come with words but with feelings, half unconscious. We begin to sense the possibility of feeling the world around us, even the universe, as a nurturing environment, as ultimately trustworthy. We are baptized into a faith in love. My mother, so many years ago, confirmed that baptism with her telling me about Jesus.

The Birth of Theology

Very quickly our religious imaginations come into play, often influenced by parents and friends. Enter theology. We may imagine this more cosmic love as a person -- an Abba or an Amma, except magnified by infinity. Or, alternatively, we may imagine this cosmic love as a field of force that has love as its essence, but which is best described in less personal terminology: the pattern that connects things, the spirit of compassion, the love from which the universe unfolds. In the first instance, the cosmic love is a personal God with intentions and feelings of her own; in the second instance the cosmic love is a transpersonal force that is better named "it" than "she" or "he."

Of course there are many places in between these two alternatives, and many people find themselves vacillating between the two poles -- one personal and one transpersonal -- in the course of a given day, relative to circumstance. I myself am among the vacillators. Sometimes it seems best to speak of cosmic love as a Holy Spirit without clearly-defined human-like characteristics, and sometimes as a cosmic Self in whose presence the universe lives and moves and has its being.

Thomas Oord seems to be in the personalist camp. Thus his book will speak to those who are inclined to imagine God as a cosmic Self but not to those who imagine God as a transpersonal force. What is important to note is that, whether personalists or transpersonalists, we ask the very question Oord also asks. To reiterate: we do not ask that the love in which we place our faith be all-powerful. We ask that it be very powerful and steadfast, such that our faith can be sustained even in hard times. We can lean on it and lean in it.

Coming to Faith in Love

Of course many, many people do not come to faith easily. Their childhoods are not nurturing at all, or not nurturing enough to inspire faith in love. Their arrival at such faith comes primarily through later life experience, perhaps associated with a community of faith (church, synagogue, mosque, sangha), not family environment. Faith in love is, for them, an acquired faith.

William James speaks of two kinds of people in the world: the once-born and the twice-born. The once-born have an optimistic and sometimes overly simple view of life, in part because they have never faced tragedy. If they are optimistic, if they lean toward love, they do so easily. The twice-born have known tragedy, understand the ambiguity of life, and can never look at the world in simple categories. If they have faith in love, it is a twice-born faith.

Many twice-born love-leaners have been tempted by bitterness and collapse. They know what it is like to crumble or, just as hard, to see others crumble around them. But over time they come to hope that, somehow, love is the guiding spirit of the universe, despite the terrible suffering they witness around them and suffer themselves. Others, perhaps the once-borners, may or may not have faced the tragedies, but their hearts are animated by the beauty in the world, human and more than human, and by the kindness they see in others.

Truth be told, our world contains both tragedy and beauty, garbage and flowers. As Whitehead put it: the fairies dance and Christ is nailed to the cross. Our hearts can lean toward love from both vantage points. The dichotomy between once-born and twice-born is but a heuristic tool. Each of us has once-born moments and twice-born moments and we evolve through time with such vacillations,

God Can't and God Can

Thomas Oord's God Can't, then, is written for the love-leaners of the world. Or, more specifically, for the Christian love-leaners who want to believe in a personal God (an Abba or Amma) but who have been shaken to the core by tragedy. On the one hand they want to believe that the love around which they seek to center their lives is in fact God, or part of God. They want to believe that God is love. On the other hand they cannot reconcile the idea that God is love with the genuine evil that shakes them: "rape, betrayal, genocide, theft, abuse, cancer, torture, murder, corruption, incest, disease, war, and more." The reconciliation they seek is not simply intellectual. It is existential and emotional. It is religious.

The questions they ask are very straightforward. If God is love, why is there so much evil? Why doesn't God intervene from time to time and prevent it? Or why didn't God create a world in which there wouldn't be so much evil in the first place? Is God able to intervene, but simply doesn't? Or was God able to create a world in which there would be less suffering, but didn't?

Oord answers these questions with the expression "God Can't" and then explains his answer biblically and philosophically. His view is that God does not, and cannot, act in purely manipulative or unilateral ways to prevent evil. It's not just that God can but chooses not to prevent evil, which would mean that God "allows" rape, betrayal, genocide, theft, abuse, torture, corruption, incest, disease, war, and more." It is that God cannot do so, because God is love.

Who would disagree? Well, for one, those who think God is, in their language, self-limiting. In their view God could prevent evil or create a world in which there is less of it, but God limits "himself" (this God is almost always male) for the sake of human freedom and mutuality. Oord disagrees vehemently with them.

Oord has a point. Sometimes images of God contradict our impulses to trust in love. If we imagine God as a Brick Wall, or the CEO of the universe, or a Clean Freak, or a detached Eye in the Sky, it can be hard to say that love is at the heart of the universe, because we see God as the heart itself, and God is not all that loving. So much of Oord's book is aimed at dispelling, indeed refuting, these images in order to make space for a truly loving God, personally conceived. Oord’s book will be most meaningful for a certain kind of Christian who has grown up with the image of a God who is, or could be, in complete control of the universe -- a certain kind of Christian who cannot reconcile this image of God with the facts of pain and tragedy. Through anecdote, metaphor, and philosophical analysis, Oord rejects this image of God and presents the alternative image of a God who is infinitely loving but who cannot control all things. (He did the same in an earlier book, The Uncontrolling Love of God.)

The God whom Oord describes is not the self-limiting God who could act unilaterally but chooses not to; instead it is a God who cannot, and never has, acted in such a way, because God’s very nature is love. This can be a breath of very fresh air to such people. Still, there are at least four kinds of readers who may not find Oord's book helpful. I have talked with them, so I speak from personal experience.

Yes, these are problems. But it is very obvious that his heart leans out toward love, and he can help certain kinds of people whose hearts likewise lean in this direction, and who want to believe that when they pray, Someone is indeed listening and responding. He gives us the image of a personal God in whose arms we can indeed lean and live from. Yes, I think Suzanne would understand.

I think Suzanne might understand the motivation of Thomas Oord's book. I'm talking about the Suzanne of Leonard Cohen's song, as sung by Judy Collins. The one who sees heroes in the seaweed and children in the morning, and who is leaning out for love and will lean that way forever.

Thomas Oord's God Can't is leaning out for love, too. Don't let its title deceive you. He wants to talk about a Love that is at the center of the universe whom he names God. But he wants you to understand that there are some things that happen in the world that God can't control, because God is love. He wants you to be able to love the Love and maybe even worship it, albeit out of affection and attraction, not fear of punishment. He thinks the Love is a person and not just a force. He thinks this Love was revealed in, but not exhausted by, a young Jew from Nazareth whose healing ministry was and still is a beacon of light for the world. In God Can't Thomas Oord wants to speak to your heart.

If you are a theologian you might not recognize Oord's pastoral aim at first. You might think Thomas Oord's God Can't is all about a battle royale between those who hold (what he takes to be) right ways of thinking about God and those who hold (what he takes to be) wrong ways of thinking about God, given the problem of evil in the world. By evil he means pain and tragedy from which there is no compensating good. Oord is, after all, an evangelical Christian, trained in traditions of theological debate where writers (mostly male) speak with authoritative voices in terms of right view and wrong views. They like to "argue" with each other. They draw lines and defend "positions." They prize "clarity" as if clarity were a god in its own right. Often they speak in what the novelist Ursula K. Le Guin calls a male, authoritarian voice -- declarative and argumentative -- even if they happen to be women. These theologians are not as good at telling stories or accepting life's ambiguities. They can't see heroes in the seaweed.

God Can't is less argumentative and more pastoral. It has lots and lots and lots of stories. It is written most specifically for a Christian whose heart leans out toward love, but who was taught, perhaps at an early age, that the universe is overseen by an all-powerful God who can do anything "he" wants. This Christian is troubled and perhaps tormented by the fact that there is so much tragedy in the world and that, in fact, God doesn't really do anything about it. God seems distant and cold, like a king on a throne. Or perhaps parental, but more like a strict and flattery-preoccupied father than a loving Abba. The Christian begins to wonder if God is really loving at all. Or perhaps even exists at all. The Christian leans out for love, but isn't sure God can be leaned on. Thomas Oord wants to give this Christian something to lean on.

Leaning out toward Love

But let's back up. There are many people in the world whose hearts lean out toward love, and they are not just Christians. Some are religiously affiliated; some are not; and many are somewhere in between. Together they form an extended family of love-leaners. One my favorite theologians, Rabbi Bradley Artson, is a Jewish love-leaner; another, Shoryu Bradley, is a Buddhist love-leaner; still another, Farhan Shah, is a Muslim love-leaner. In the house of love-leaners there are many rooms. My mother, Virginia McDaniel, was a love-leaner, too. I remember asking her one time, when I was about six years old, who Jesus was, and she said, "He is someone who is always holding your hand even when you don't know it."

My mother captured what love-leaners feel. They -- we -- feel that somehow, some way, there's something in the universe, deeply compassionate, that is always holding everyone's hands, even when they don't know it. Or at least we want to believe this. We want to believe that love is more ultimate than anything else. We do not ask that love be all-powerful, but we do ask that love be more fundamental than the violence and the sadness. We want to have faith in love.

Infant Baptism

How does our faith in love emerge? There may or may not be some gene in our bodies which inclines us to lean toward love from the very outset of life. I suspect there is, but I'll leave that to the biologists.

One thing is clear. The impulse toward love-leaning is connected to the impulse toward trust in a nurturing environment, and the latter impulse, whether activated or not, is part of our lives from a very early age. Biologically and psychologically, indeed spiritually, we need to trust in nurturance from a very early age. We are born with what Muslims call fitra: a disposition to sense, and feel protected by, a unity beyond our ken, of which we are a part.

For most of us, the trust is satisfied at an early age, with milk. As soon as we survive the trial of birth, and rest in our mother's arms, we begin to sense the possibility of trusting in a nurturing environment.

Not much later, in early childhood if not in infancy, this trust can be nurtured by our families, if we are very lucky. If we had loving families, where we ourselves felt loved, the parental and familial love we received as children became, for us, a window into something deep and wonderful: a kind of supportive love that is more than even our parents. This feeling of a wider love is our first intuition that God is Love. It does not come with words but with feelings, half unconscious. We begin to sense the possibility of feeling the world around us, even the universe, as a nurturing environment, as ultimately trustworthy. We are baptized into a faith in love. My mother, so many years ago, confirmed that baptism with her telling me about Jesus.

The Birth of Theology

Very quickly our religious imaginations come into play, often influenced by parents and friends. Enter theology. We may imagine this more cosmic love as a person -- an Abba or an Amma, except magnified by infinity. Or, alternatively, we may imagine this cosmic love as a field of force that has love as its essence, but which is best described in less personal terminology: the pattern that connects things, the spirit of compassion, the love from which the universe unfolds. In the first instance, the cosmic love is a personal God with intentions and feelings of her own; in the second instance the cosmic love is a transpersonal force that is better named "it" than "she" or "he."

Of course there are many places in between these two alternatives, and many people find themselves vacillating between the two poles -- one personal and one transpersonal -- in the course of a given day, relative to circumstance. I myself am among the vacillators. Sometimes it seems best to speak of cosmic love as a Holy Spirit without clearly-defined human-like characteristics, and sometimes as a cosmic Self in whose presence the universe lives and moves and has its being.

Thomas Oord seems to be in the personalist camp. Thus his book will speak to those who are inclined to imagine God as a cosmic Self but not to those who imagine God as a transpersonal force. What is important to note is that, whether personalists or transpersonalists, we ask the very question Oord also asks. To reiterate: we do not ask that the love in which we place our faith be all-powerful. We ask that it be very powerful and steadfast, such that our faith can be sustained even in hard times. We can lean on it and lean in it.

Coming to Faith in Love

Of course many, many people do not come to faith easily. Their childhoods are not nurturing at all, or not nurturing enough to inspire faith in love. Their arrival at such faith comes primarily through later life experience, perhaps associated with a community of faith (church, synagogue, mosque, sangha), not family environment. Faith in love is, for them, an acquired faith.

William James speaks of two kinds of people in the world: the once-born and the twice-born. The once-born have an optimistic and sometimes overly simple view of life, in part because they have never faced tragedy. If they are optimistic, if they lean toward love, they do so easily. The twice-born have known tragedy, understand the ambiguity of life, and can never look at the world in simple categories. If they have faith in love, it is a twice-born faith.

Many twice-born love-leaners have been tempted by bitterness and collapse. They know what it is like to crumble or, just as hard, to see others crumble around them. But over time they come to hope that, somehow, love is the guiding spirit of the universe, despite the terrible suffering they witness around them and suffer themselves. Others, perhaps the once-borners, may or may not have faced the tragedies, but their hearts are animated by the beauty in the world, human and more than human, and by the kindness they see in others.

Truth be told, our world contains both tragedy and beauty, garbage and flowers. As Whitehead put it: the fairies dance and Christ is nailed to the cross. Our hearts can lean toward love from both vantage points. The dichotomy between once-born and twice-born is but a heuristic tool. Each of us has once-born moments and twice-born moments and we evolve through time with such vacillations,

God Can't and God Can

Thomas Oord's God Can't, then, is written for the love-leaners of the world. Or, more specifically, for the Christian love-leaners who want to believe in a personal God (an Abba or Amma) but who have been shaken to the core by tragedy. On the one hand they want to believe that the love around which they seek to center their lives is in fact God, or part of God. They want to believe that God is love. On the other hand they cannot reconcile the idea that God is love with the genuine evil that shakes them: "rape, betrayal, genocide, theft, abuse, cancer, torture, murder, corruption, incest, disease, war, and more." The reconciliation they seek is not simply intellectual. It is existential and emotional. It is religious.

The questions they ask are very straightforward. If God is love, why is there so much evil? Why doesn't God intervene from time to time and prevent it? Or why didn't God create a world in which there wouldn't be so much evil in the first place? Is God able to intervene, but simply doesn't? Or was God able to create a world in which there would be less suffering, but didn't?

Oord answers these questions with the expression "God Can't" and then explains his answer biblically and philosophically. His view is that God does not, and cannot, act in purely manipulative or unilateral ways to prevent evil. It's not just that God can but chooses not to prevent evil, which would mean that God "allows" rape, betrayal, genocide, theft, abuse, torture, corruption, incest, disease, war, and more." It is that God cannot do so, because God is love.

Who would disagree? Well, for one, those who think God is, in their language, self-limiting. In their view God could prevent evil or create a world in which there is less of it, but God limits "himself" (this God is almost always male) for the sake of human freedom and mutuality. Oord disagrees vehemently with them.

Oord has a point. Sometimes images of God contradict our impulses to trust in love. If we imagine God as a Brick Wall, or the CEO of the universe, or a Clean Freak, or a detached Eye in the Sky, it can be hard to say that love is at the heart of the universe, because we see God as the heart itself, and God is not all that loving. So much of Oord's book is aimed at dispelling, indeed refuting, these images in order to make space for a truly loving God, personally conceived. Oord’s book will be most meaningful for a certain kind of Christian who has grown up with the image of a God who is, or could be, in complete control of the universe -- a certain kind of Christian who cannot reconcile this image of God with the facts of pain and tragedy. Through anecdote, metaphor, and philosophical analysis, Oord rejects this image of God and presents the alternative image of a God who is infinitely loving but who cannot control all things. (He did the same in an earlier book, The Uncontrolling Love of God.)

The God whom Oord describes is not the self-limiting God who could act unilaterally but chooses not to; instead it is a God who cannot, and never has, acted in such a way, because God’s very nature is love. This can be a breath of very fresh air to such people. Still, there are at least four kinds of readers who may not find Oord's book helpful. I have talked with them, so I speak from personal experience.

- More orthodox Christians who lean toward love, but find inspiration for leaning in, not apart from, more traditional imagery, Oord’s points notwithstanding.

- People who believe in a personal God, but who have never been tempted by images of God as controlling power, and who can’t quite understand what all the fuss is about.

- People who belong to other religions in which images of a controlling God have never been paramount.

- Spiritual independents – i.e. the spiritual but not religious – for whom images of a powerful, controlling God are not at all tempting in the first place. For the latter three, Oord is waging battles of which they are not a part.

Yes, these are problems. But it is very obvious that his heart leans out toward love, and he can help certain kinds of people whose hearts likewise lean in this direction, and who want to believe that when they pray, Someone is indeed listening and responding. He gives us the image of a personal God in whose arms we can indeed lean and live from. Yes, I think Suzanne would understand.

Who God Is

|

Who God is Not

|