Alternative Worlds

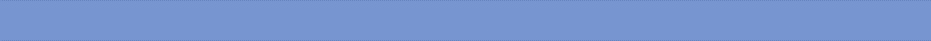

Ursulu K. Le Guin, Process Theology,

and the Kesh People

“Love doesn't just sit there, like a stone, it has to be made, like bread;

remade all the time, made new.”

-- Ursula K. Le Guin

"The people in this book might be going to have lived a long, long time

from now in Northern California"

-- Ursula K. Le Guin

Learning from the Kesh People

When did the Kesh live? They haven't, yet. The Kesh have access to a daunting computer system. But they live 500 years or more in our future, on the northwestern coast of what's left of a United States gone low-tech and depopulated by toxic wastes and radioac-tive contamination. The Kesh are an attractive people. One noun serves them for both gift and wealth. To be rich and to give are, for them, one verb. They do not share the West's present passion for origins and outcomes: their pivotal cultural concept is the hinge, the connecting principle that allows things both to hold together and to move in relation to each other. Their year is marked off by elaborate seasonal dances. Their lives and work are organized in a complicated system of Houses, Lodges, Arts, and Societies. (From NY Times Book Review, Samuel, R. Delany, Sept.. 29, 1985)

Theology of the Kesh

Ursula Le Guin's many influences included the poetry of Wordsworth, the psychology of Jung, and the philosophical ontology of Taoism. That's enough to bring her close to many process theologians, especially feminist process thinkers. Along with process theologians influenced by the ideal of ecological civilization, she wants to speak the earth tongue. In Le Guin's case this tongue takes the form of stories, which she calls the mother's tongue. A problem with process theology is that it is far too often the father's tongue. Moreover, Le Guin was not much interested (or at all interested) in answering the the question of God's existence, which has preoccupied more than a few process theologians She writes:

“To be an atheist is to maintain God. His existence or his non existence, it amounts to much the same, on the plane of proof. Thus proof is a word not often used among the Handdarata, who have chosen not to treat God as a fact, subject either to proof or to belief: and they have broken the circle, and go free. To learn which questions are unanswerable, and not to answer them: this skill is most needful in times of stress and darkness.” ― Ursula K. Le Guin, The Left Hand of Darkness

Thus it can seem as if Le Guin is a far cry from "speculative" philosophy which speculates, among other things, about the nature of God. (See God with a Spacious Heart or Panetheism: The World as God's Body.) But her science fiction points in another direction. Call it speculative anthropology. She wants to imagine how we humans might live on a small, beautiful and fragile planet in ways that are respectful, free, egalitarian, diverse, and fun. Process theologians imagine the same and call it "ecological civilization." Speaking with her mother's tongue, she presents images of such a civilization, as exemplified among many places in the Kesh, who seem especially attuned to movement (process) and who believe in a human capacity to move with one another and other creatures in creative and kindly ways. The implicit aim of much process theology is to encourage a theology of the Kesh.

-- Jay McDaniel

-- Jay McDaniel

Earth tongue, father tongue, mother tongue

the earth tongue"And when you fail, and are defeated, and in pain, and in the dark, then I hope you will remember that darkness is your country, where you live, where no wars are fought and no wars are won, but where the future is. Our roots are in the dark; the earth is our country. Why did we look up for blessing — instead of around, and down? What hope we have lies there. Not in the sky full of orbiting spy-eyes and weaponry, but in the earth we have looked down upon. Not from above, but from below. Not in the light that blinds, but in the dark that nourishes, where human beings grow human souls." Writer Ursula K. Le Guin (1929-2018) was "a one-woman revolution in fiction and fantasy." She wrote 21 novels, 11 volumes of short stories, four collections of essays, 12 children's books, six volumes of poetry, and four of translation.

|

the father tongue"The political tongue speaks aloud-and look how radio and television have brought the language of politics right back where it belongs - but the dialect of the father tongue that you and I learned best in college is a written one. It doesn't speak itself. It only lectures. It began to develop when printing made written language common rather than rare, five hundred years ago or so, and with electronic processing and copying it continues to develop and proliferate so powerfully, so dominatingly, that many believe this dialect - the expository and particularly the scientific discourse - is the highest form of language, the true language, of which all other uses of words are primitive vestiges." the mother tongue"People crave objectivity because to be subjective is to be embodied, to be a body, vulnerable, violable. Men especially aren't used to that; they're trained not to offer but to attack. It's often easier for women to trust one another, to try to speak our experience in our own language, the language we talk to each other in, the mother tongue; so we empower each other. |

The Need for Unprecedented Imagination

"Unprecedented crises require unprecedented cooperation."-Wm. Andrew Schwartz of Ecological Civilization

Andrew Schwartz of the Institute for Ecological Civilization, executive director of the Center for Process Studies, reminds us that unprecedented crises require unprecedented cooperation.

|

Ursula K. Le Guin Speaks (and Margart Atwood, too)

|

In this wide-ranging conversation from 2015, Ursula K. Le Guin talks to Zoë Carpenter about climate change, the definition of progress, and how "the future in science fiction is just a metaphor for now."

|

"The Tribute featured tributes from writers and friends who represent the wide-ranging influence Le Guin has had on international literature for more than 50 years. Author Margaret Atwood appeared via this recorded message,"

|

Music and Poetry of the Kesh

music and poetry of The Keshearth-based spirituality"The songs of the Kesh speak to an earth-based spirituality, referencing ceremonies of actual Native Americans: “Sun Dance Poem,” “A River Song,”; there are songs for willow trees, dragonflies, herons, and quail. The titles alone are risky; are these cultural appropriations? In the wrong hands, they could be, of course, particularly if Le Guin and Barton had opted to base them on actual sacred or ceremonial songs. But Le Guin resolved instead to listen not so much to other music but to the land itself, as she had done since childhood." |

poets as realists of a larger reality“Hard times are coming, when we’ll be wanting the voices of writers who can see alternatives to how we live now, can see through our fear-stricken society and its obsessive technologies to other ways of being, and even imagine real grounds for hope,” Le Guin said in a fiery speech at the 2014 National Book Awards. “We’ll need writers who can remember freedom—poets, visionaries—realists of a larger reality.” we need to hear their music, too"In her final months, she was preparing the re-release of a 1985 work that had largely flown under the radar. Music and Poetry of the Kesh,her collaborative album with composer and analog synthesist Todd Barton, was first issued on cassette in 1985, bundled with Le Guin’s novel Always Coming Home, a dark-horse favorite among her readers. It’s an expansive, 523-page portrayal of a future tribe of indigenous people living an anti-colonial existence 500 years from now, their lives ruled by nature and the seasons, their story told by Le Guin in fiction, poetry, plays, recipes, ethnography, a glossary, and hand-drawn maps. Even given those wildly melding genres, Le Guin claimed she needed to “hear the music,” too. She enlisted Barton and began an elaborate and carefully considered process that yielded the deceptively verisimilar Music and Poetry of the Kesh." |

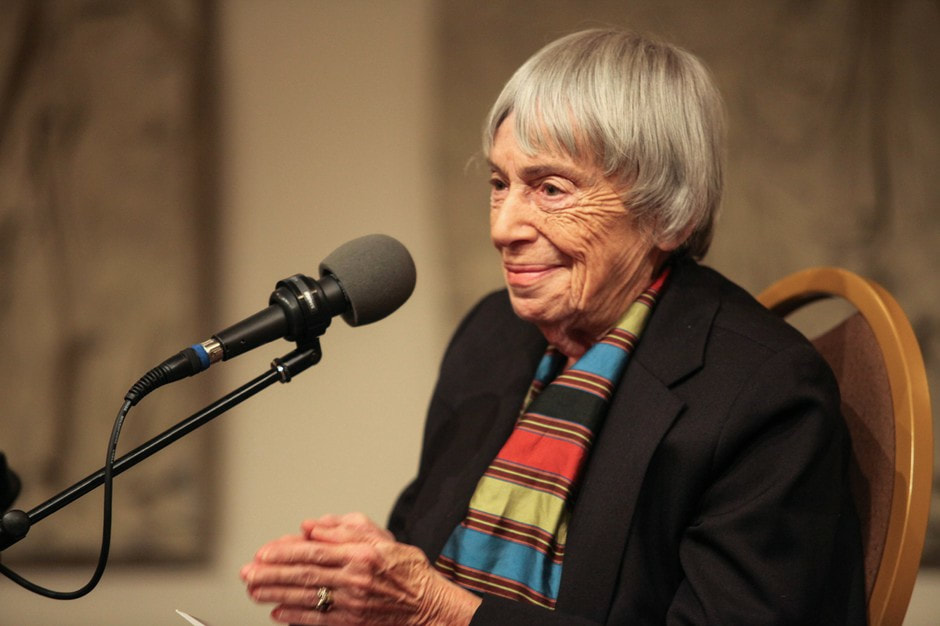

Excerpts from Book Review of Always Coming Home

by James Schellenberg in Challenging Destiny

Always Coming Home was six years in the making, a massive project involving Le Guin's best efforts to create an entire culture, convincing, complete, and worth reading about. It's largely a book of fragments -- songs, stories, poems, anecdotes, dramatic works, maps, illustrations, recipes, genealogies, and personal tales -- all in support of transporting the reader to a Northern California of some time not our own. As Le Guin puts it in her brief "A First Note": "The people in this book might be going to have lived a long, long time from now in Northern California" (xi).

*

Most intriguingly, this original box set of Always Coming Home by Harper and Row includes a cassette tape, Music & Poetry of the Kesh. For this part of the project, Le Guin collaborated with Todd Barton to create thirteen tracks in all, with three recitations of poetry from the book and ten original songs by Barton. The music is clearly folk music, very low on production values, as is appropriate. The lyrics are also sung in the original language of the Kesh, with a translation into English for each song in the accompanying booklet (the entire book is conceived of as a translation from the Kesh by Le Guin, which I'll discuss further, but we only get smatterings of the language in the book). The booklet also explains the context of each song. For example, this is the description for "Yes-Singing":

Words and tune of this song are traditional, more or less, but not sacred. The singers were teasing, provocative, and seductive; the men they were singing at tried hard to pay no attention, being held to celibacy for the period before the Moon Dance. The recording, made on the common place of Sinshan, may give a hint of the tense, wild atmosphere in town before the First Night of the Moon. The singers were Thorn, Chickadee, and River Flowing Northwest.

And yes, the song lives up to its billing (and there's a much longer description of the Moon Dance in the book). Most of the other music is less tense and wild, like the mood piece "Long Singing" which is described an excerpt from an all-night midwinter singing ritual. On the whole, the music is more haunting than catchy, but it's a nifty way of giving the reader an entrance point into this world.

What Sort of World Do We Want to Live In? |