- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

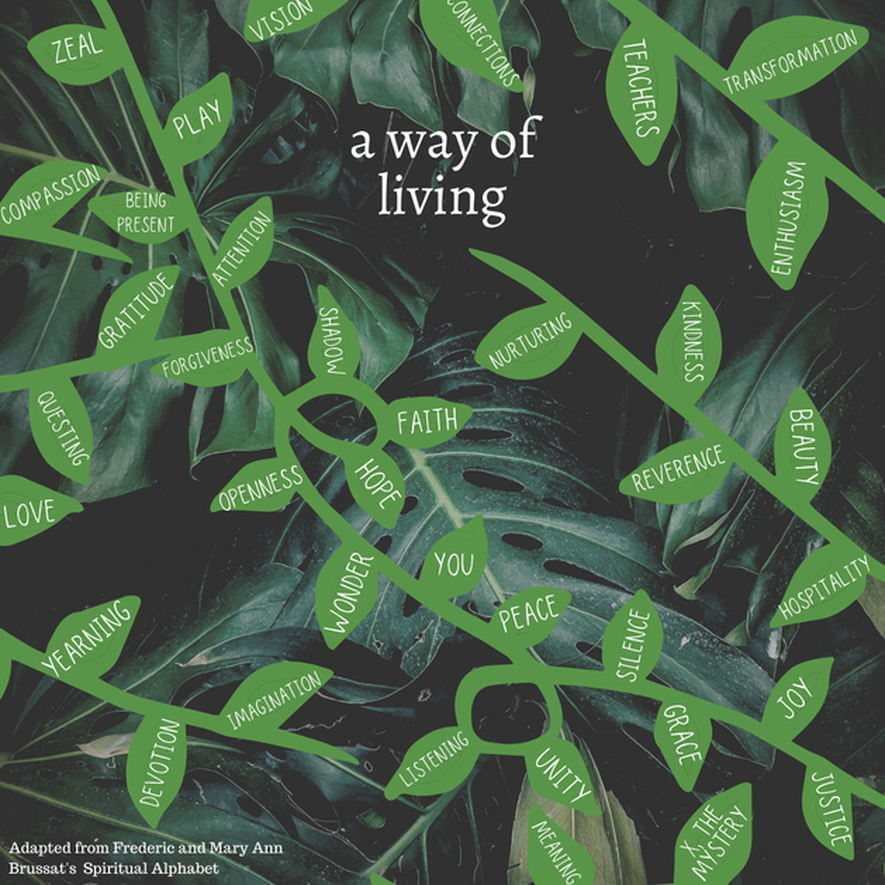

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

Compassion Education

Dr. Frank Rogers

From The Essential Components of Compassion: The Pulse Method (Dr. Frank Rogers, Claremont Center for Engaged Compassion). Reprinted with his permission.

“The pulse of compassion beats within us all. The essence of this pulse is straightforward. Compassion is simply “being moved in one’s depths by another’s experience, and responding in a way that intends either to ease their suffering or promote their flourishing.” Metaphorically, compassion is a movement of the heart, the quiver we feel, for example, when we see someone in pain. The compassionate heart, we say, is soft and tender. In contrast to the cold or hard heart of one unmoved by suffering, it beats freely, supple enough to take in another’s pain, to be moved, and to respond with acts of kindness, good will, healing, and justice.

.

Often this pulse happens naturally and with an elegant simplicity, like when a child notices a wounded puppy, is moved by its mournful eyes, and soothes it with a tender caress. Other times, the process is agonizing and complex and requires a sustained commitment to one’s own healing and the spiritual practices that support it. Either way, this compassionate pulse, when examined more closely, has several essential components. Though sometimes implicit or so subtle as to seem instinctive, every experience of compassion involves the following six dimensions:

1. Paying attention (Contemplative awareness). A precondition for compassion is a particular way of seeing others. Usually when we relate to one another we do so through judgments and reactions that are conditioned by our own needs, desires, feelings, and sensitivities. We do not see other persons on their own terms; rather, we perceive them through the filtered lenses of our own agendas. I seldom see my son, Justin, for example, in the poignant particularity of his longings and fears, wounds and delights—I usually see him as the forgetful college kid who neglects to pick up his dishes, or the straight-A student about whom I like to brag to my colleagues. Either way, he becomes objectified, a virtual pawn in my own personal projects, not a subject with depth and uniqueness.

Contemplative awareness, as Walter J. Burghardt classically defined it, entails “a long, loving look at the real.” We experience contemplative awareness through the nonreactive, non-projective apprehension of others in the mystery of their uniqueness….The recipient knows the difference between being seen and objectified. Compassion engenders the sense of truly being seen without the distortional filter of another’s judgments or agenda.

2. Understanding empathically (Empathic care). Compassion entails being moved by another’s experience. In Pali, Arabic, Hebrew, and Greek, the etymological roots for the primary words translated as compassion are linked to a person’s vital organs—specifically the womb, heart, belly, and bowels. In essence, when we are moved to compassion, our depths are stirred—often viscerally. When Muhammad, for example, sees the plight of a widow or when Jesus surveys the pain of Jerusalem, they are gut-wrenched before the suffering, heartbroken, sickened to the stomach, their womb-like cores contract. In contrast to the coldness and indifference of the unmoved, a compassionate person allows another’s pain or joy to reverberate within his or her deepest core such that he or she is moved to pathos before the other’s suffering or stirred to delight before the other’s flourishing. A compassionate person understands, in his or her depths, the wounds, heartaches, and longings at the core of another person’s behavior and experience.

3. Loving with connection (All-accepting presence). A nonjudgmental, all-embracing, infinitely loving quality resides at the core of compassion. Like the mother cradling her child, the womb-like love of compassion carries no hint of shame, critique, aversion, or belittlement. Rather, it wells up with a connective care that extends toward the other like the soothing wash of the sunlight’s warmth.

4. Sensing the sacredness (Spiritual expansiveness). Compassion is a spiritual energy. When our hearts open to others’ suffering and a sustaining love flows through us, the veil of the everyday world we live in is pierced and relativized: time seems to stop; errands lose their urgency; perennial irritations can feel petty and frivolous. In those moments, our spirits expand—our capacity to care deepens; our understanding for the plight of another extends; our patience can seem infinite; grace abounds.

Some people experience these compassion-filled moments as holy. These moments are icons of a sacred energy, cosmic and benevolent. They are portals of presence that remind us that compassion flows not from our hearts alone but from the very texture of the universe. We are plugged into, and instruments of, a cosmic field of loving energy that reverberates throughout all time and space, carefully holds every scar and wound no matter how deep or brutal, and seeps through the open heart willing to be the instrument of care for another.

5. Embodying new life (Desire for flourishing). Compassion not only grieves with the wounded in pain but also yearns for suffering to be transformed into joy. Compassion celebrates when new life is birthed and embodied. Like the womb that receives and incubates with protective care, holding another’s pain brings about life. Genuine compassion is not limited to moments of suffering, offering an empathic connection only as long as the other is in pain. Genuine compassion takes as much delight in others’ flourishing as it feels pathos for their pain. Indeed, pathos, when soaked with compassionate care, gives rise to the yearning that wounded persons flourish with the fullness of life .

6. Restorative Action: The sentiment of compassion does not close in on itself. It does not soak in a moment of tender pathos then simply walk away. Compassion is responsive. It takes some step toward easing others’ suffering and nurturing their flourishing. A mother cradling a sick child searches for medicine that will heal; television images of a hurricane’s destruction give rise to relief trips delivering supplies and repairing the damage.

Compassion includes restorative action. Without it, compassion degenerates into sentimentality—feeling bad for others’ pain but ultimately abandoning them to fend for themselves. Compassion walks toward not away. It sits with the grieving, companions the forlorn, and walks shoulder-to-shoulder with those on the road pushing toward liberation. As the Jewish prophet Abraham Heschel remembered his marching beside Martin Luther King Jr. at the Selma march, in the way of compassion, there comes a time to pray with our legs.”

“The pulse of compassion beats within us all. The essence of this pulse is straightforward. Compassion is simply “being moved in one’s depths by another’s experience, and responding in a way that intends either to ease their suffering or promote their flourishing.” Metaphorically, compassion is a movement of the heart, the quiver we feel, for example, when we see someone in pain. The compassionate heart, we say, is soft and tender. In contrast to the cold or hard heart of one unmoved by suffering, it beats freely, supple enough to take in another’s pain, to be moved, and to respond with acts of kindness, good will, healing, and justice.

.

Often this pulse happens naturally and with an elegant simplicity, like when a child notices a wounded puppy, is moved by its mournful eyes, and soothes it with a tender caress. Other times, the process is agonizing and complex and requires a sustained commitment to one’s own healing and the spiritual practices that support it. Either way, this compassionate pulse, when examined more closely, has several essential components. Though sometimes implicit or so subtle as to seem instinctive, every experience of compassion involves the following six dimensions:

1. Paying attention (Contemplative awareness). A precondition for compassion is a particular way of seeing others. Usually when we relate to one another we do so through judgments and reactions that are conditioned by our own needs, desires, feelings, and sensitivities. We do not see other persons on their own terms; rather, we perceive them through the filtered lenses of our own agendas. I seldom see my son, Justin, for example, in the poignant particularity of his longings and fears, wounds and delights—I usually see him as the forgetful college kid who neglects to pick up his dishes, or the straight-A student about whom I like to brag to my colleagues. Either way, he becomes objectified, a virtual pawn in my own personal projects, not a subject with depth and uniqueness.

Contemplative awareness, as Walter J. Burghardt classically defined it, entails “a long, loving look at the real.” We experience contemplative awareness through the nonreactive, non-projective apprehension of others in the mystery of their uniqueness….The recipient knows the difference between being seen and objectified. Compassion engenders the sense of truly being seen without the distortional filter of another’s judgments or agenda.

2. Understanding empathically (Empathic care). Compassion entails being moved by another’s experience. In Pali, Arabic, Hebrew, and Greek, the etymological roots for the primary words translated as compassion are linked to a person’s vital organs—specifically the womb, heart, belly, and bowels. In essence, when we are moved to compassion, our depths are stirred—often viscerally. When Muhammad, for example, sees the plight of a widow or when Jesus surveys the pain of Jerusalem, they are gut-wrenched before the suffering, heartbroken, sickened to the stomach, their womb-like cores contract. In contrast to the coldness and indifference of the unmoved, a compassionate person allows another’s pain or joy to reverberate within his or her deepest core such that he or she is moved to pathos before the other’s suffering or stirred to delight before the other’s flourishing. A compassionate person understands, in his or her depths, the wounds, heartaches, and longings at the core of another person’s behavior and experience.

3. Loving with connection (All-accepting presence). A nonjudgmental, all-embracing, infinitely loving quality resides at the core of compassion. Like the mother cradling her child, the womb-like love of compassion carries no hint of shame, critique, aversion, or belittlement. Rather, it wells up with a connective care that extends toward the other like the soothing wash of the sunlight’s warmth.

4. Sensing the sacredness (Spiritual expansiveness). Compassion is a spiritual energy. When our hearts open to others’ suffering and a sustaining love flows through us, the veil of the everyday world we live in is pierced and relativized: time seems to stop; errands lose their urgency; perennial irritations can feel petty and frivolous. In those moments, our spirits expand—our capacity to care deepens; our understanding for the plight of another extends; our patience can seem infinite; grace abounds.

Some people experience these compassion-filled moments as holy. These moments are icons of a sacred energy, cosmic and benevolent. They are portals of presence that remind us that compassion flows not from our hearts alone but from the very texture of the universe. We are plugged into, and instruments of, a cosmic field of loving energy that reverberates throughout all time and space, carefully holds every scar and wound no matter how deep or brutal, and seeps through the open heart willing to be the instrument of care for another.

5. Embodying new life (Desire for flourishing). Compassion not only grieves with the wounded in pain but also yearns for suffering to be transformed into joy. Compassion celebrates when new life is birthed and embodied. Like the womb that receives and incubates with protective care, holding another’s pain brings about life. Genuine compassion is not limited to moments of suffering, offering an empathic connection only as long as the other is in pain. Genuine compassion takes as much delight in others’ flourishing as it feels pathos for their pain. Indeed, pathos, when soaked with compassionate care, gives rise to the yearning that wounded persons flourish with the fullness of life .

6. Restorative Action: The sentiment of compassion does not close in on itself. It does not soak in a moment of tender pathos then simply walk away. Compassion is responsive. It takes some step toward easing others’ suffering and nurturing their flourishing. A mother cradling a sick child searches for medicine that will heal; television images of a hurricane’s destruction give rise to relief trips delivering supplies and repairing the damage.

Compassion includes restorative action. Without it, compassion degenerates into sentimentality—feeling bad for others’ pain but ultimately abandoning them to fend for themselves. Compassion walks toward not away. It sits with the grieving, companions the forlorn, and walks shoulder-to-shoulder with those on the road pushing toward liberation. As the Jewish prophet Abraham Heschel remembered his marching beside Martin Luther King Jr. at the Selma march, in the way of compassion, there comes a time to pray with our legs.”

Education for the Whole Person

in an Ecological Civilization

An ecological civilization consists of local communities in urban and rural settings whose citizens live with respect and care for one another and the larger community of life. They live within the limits of the earth to supply resources and leave space for wildnerness. Their food is healthy and their air is clean. Their hands are not raised except in greeting. Their communities are creative, compassionate, participatory, diverse, inclusive, humane to animals,and good for the earth, with no one left behind.

They are wise, too. Beginning at a young age, at home and in kindergarten, they are educated not only the practical skills needed for healthy and creative living, but also in compassion, spiritual literacy, environmental appreciation, and family life. They call it education for the whole person. An emphasis on whole person education extends through formal education and afterwards. As Whitehead put it, the ultimate subject of education is life. Part of this education, a very important part, is compassion education.

They are wise, too. Beginning at a young age, at home and in kindergarten, they are educated not only the practical skills needed for healthy and creative living, but also in compassion, spiritual literacy, environmental appreciation, and family life. They call it education for the whole person. An emphasis on whole person education extends through formal education and afterwards. As Whitehead put it, the ultimate subject of education is life. Part of this education, a very important part, is compassion education.

Four Kinds of Whole Person Education

Family Life Education, Compassion Education,

Education in Environmental Appreciation,

and Education in Spiritual Literacy

Jay McDaniel

Abstract

An ecological civilization is a nurturing society. Its citizens live with respect and care for one another and the larger community of life. A society of this kind requires for four kinds of moral education: family life education, compassion education, education in spiritual literacy, and education in environmental appreciation. These four kinds of education can help people become eco-persons with wide souls, each in his or her own way. He or she lives with a spirit of respect and care, enjoying a modicum of what the Four Harmonies identified by Zhang Zhai (1020-1077) in the Western Inscription: harmony with self, harmony with other people, harmony with the natural world, and harmony with heaven. This paper introduces these kinds of education and further develops the idea of an eco-person with a wide soul. It offers a suggestion of what constructively postmodern moral education might look like.

Essay

An ecological civilization is easy to imagine and hard to realize. It consists of communities that are creative, compassionate, participatory, culturally diverse, humane to animals, ecologically wise, and spiritually satisfying – with no one left behind. Their citizens live with respect and care for the community of life and one another. They listen to one another and feel listened to, knowing that every voice counts. They belong to, and help create, what scholars have come to call a nurturing society.

The Nurturing Society

A nurturing society is a society oriented toward nurturance rather than domination, mutual support rather than hyper-competition, persuasion rather than coercion. Its citizens understand themselves as individuals, but they do not fall into a cult of individualism. They are faithful to the bonds of relationship: relationships with friends and family, to be sure, but also to neighbors and strangers, and of course to the natural world as well. The hills and rivers, the trees and stars – they, too, are their friends. They are what Zhihe Wang and Meijun Fan call eco-persons; they possess what process philosophers call wide souls. Their approach to life helps build and sustain nurturing societies -- the kind of society encouraged by constructive postmodern thinkers around the world, including those in China.

How might we grow toward this kind of society? Many of us in the constructive postmodern tradition emphasize the importance of worldviews in approximating this kind of society. We see the world as a communion of subjects, not a collection of objects, and we believe that seeing the world this way can help us live more lightly on the earth and gently with one another. We talk about a universe which is filled with mutual becoming and intrinsic value, and about the priority of persuasive power over coercive power. We propose that the universe carries within it a normative dimension: a lure toward truth and goodness and beauty, toward wisdom and compassion and creativity. We recognize that many worldviews can point in this direction, but we are especially impressed with that of Alfred North Whitehead, because he helps us understand how such an organic worldview can be both scientific and spiritual, neither to the exclusion of the other.

But our focus on worldview can be overly abstract and short-sighted if it fails to attend to on-the-ground, empirical realities. One of them, for example, is family life. Today, a vast range of research literature from psychology, cognitive linguistics, and political science shows that the emergence of a nurturing society is closely connected with parenting styles in early childhood.

Nurturing parenting styles are neither overly permissive nor overly authoritarian. They combine loving support with discipline, affection with authority. The children of such parents typically feel listened to and respected as they are willing to receive instructions and constructive criticism. In a word, they feel loved. Children with nurturing parents grow up combining pro-social traits such as friendliness, a capacity for listening, and an ability to cooperate with others with individualized traits such as a capacity to think for themselves, take initiative, and act independently. They are the kinds of people who can build and help sustain ecological civilizations.

The alternative parenting style is authoritarian. Here a distinction is important between authoritative, which is good, and authoritarian, which is problematic. The nurturing parenting style is authoritative; the nurturing parent has authority over his or her children. Some scholars speak of the nurturing style as authoritative because the parent exercises what we constructive postmodernists call persuasive or relational power, which is itself, in our view, much more powerful in the long run than coercive or unilateral power. But being authoritative in this persuasive way is very different from being authoritarian.

Authoritarian parenting style exercises its authority in a dominating and unilateral way, such that only one voice has power: that of the parent. The authoritarian parent relies on a threat of punishment, does not listen to his or her child, and emphasizes the primacy of order in the household over spontaneity and love. The results are problematic for the child. As John Sanders explains: “Children raised in strongly Authoritarian families are less able to chart their own moral course (they need someone to tell them what to do in new situations), have less of a conscience (they need an external moral guide), are less respectful of those who are different, and have less ability to resist temptations.[i]

These parenting styles carry over into all aspects of society. Educators and coaches, government officials and employers, can embody nurturing or authoritarian leadership styles. Moreover, these styles may in turn appeal to different people relative to the type of parenting style they had as children. In the United States, for example, one citizen may prefer the “strong” leader whose dominant mode of operation is a promise of restoring order by means of strict laws, whereas another citizen may prefer the “nurturing” leader whose mode of operation includes wise guidance, combined with listening and care.

Studies show as well that these two styles – the nurturing and the authoritarian – obtain in different kinds of societies as well. Again, in the words of John Sanders: “These results do not depend on social or racial background or the marital status of the parents. Furthermore, studies show the nurturing approach superior in countries around the world including China, Australia, Pakistan, and Argentina to name but a few. This is important because these counties are quite diverse in many significant respects. For example, some are collectivist while others are individualist cultures. Yet, the nurturing style is superior in these cultures as well. Studies also show that highly effective educators, coaches, and administrators use the nurturing approach. Children raised by nurturing parents and educators exhibit greater degrees of self-reliance, prosocial behavior, confidence in social settings, motivation to achieve, cheerfulness, self-control, and less substance abuse.”[ii]

Family Life Education

Needless to say, many parents and coaches, government officials and educators combine these styles. They are authoritarian in some contexts, and nurturing in other contexts. Or they send mixed signals. Nevertheless, the nurturing approach is by all means preferred by constructive postmodernists, and they – we – believe that the very future of the planet partly depends on it being prioritized in government, education, public policy as well as family life. We want to nurture the nurturing approach.

The research noted above suggests that much of this nurturance must occur at home and begin in early childhood. In social contexts where families have fallen apart, where parents are absent, or where the home atmosphere is primarily cold and disciplinarian, this kind of nurturance will not occur. One thing that a wise government can do is to develop and provide opportunities for parental training, with specific focus on how to be a nurturing parent.

The training must itself be nurturing. Parents and grandparents must feel empowered, not demeaned, as they shift from an authoritarian to a nurturing mode. And they must learn by seeing examples of the nurturing style, not simply by slogans about the virtues of nurturance. And yet parental training is not enough. In addition to training parents, citizens need to be trained about how to approach the larger society and the natural world in nurturing ways. This can best occur through moral education in public schools. [iii] By moral education I do not mean training in ethics alone. I mean training in what it means be a whole person. Three kinds of moral education are especially important.

Compassion Education, Education for Emotional/Spiritual Literacy,

And Education for Environmental Appreciation

.

The first is Compassion Education (CE): educating people in practical ways to expand their capacities for respect and care. In the United States three research centers especially promising in this regard: Stanford University’s Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education,[iv] the Center for Mindfulness Studies in Toronto, Canada[v]; and the Claremont Center for Engaged Compassion.[vi] As the Stanford center makes clear, organizations ground their work in leading-edge scientific research: brain-mind and behavior studies, clinical psychology studies, and biomedical studies. The Claremont Center trains facilitators and does “compassion work” all over the world through what it calls the Pulse Method. I offer an excerpt in Appendix A.

The second is Education for Spiritual Literacy (ESL): that is, educating people to recognize the spiritual side of their lives and the spiritual side of other people’s lives, so that they can treat themselves and other people as whole persons: that is, persons with inner capacities for curiosity and wonder, for imagination and listening, as well as for kindness and compassion. Here spirituality does not refer to religious affiliation. It refers instead to the moods and modalities found in the circle below, developed by Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat in Claremont, CA. In their wheel of spirituality they offer a vocabulary, a spiritual alphabet, for appreciating the positive emotions that people seek and feel in daily life, and which are part of what it means to be a whole person.

Spiritual literacy is closely connected to emotional intelligence. In the latter regard the pioneering work of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence is especially important.[vii] This center trains teachers throughout the United States to help children grow in emotional intelligence: knowing and managing their own emotions, understanding the emotions of others. Insofar as moral education includes education in spiritual literacy, it simultaneously included education in emotional intelligence: that is, in recognizing positive emotions in oneself and others.

The third is education for Environmental Appreciation (EA): educating people about the more-than-human world (the hills and rivers, plants and animals) and providing them with opportunities to appreciate that world, in its beauty and intrinsic value (value independent of its usefulness to human beings.) There are many examples of such education around the world and often they rely two models: a cognitive model and an aesthetic model. In the words of Chung-Ping Yang: “The former stresses the necessity of scientific knowledge, including ecology, biology, and geography, while the latter focuses more on imagination, intuition, mystery, and folktales.” See Yang’s Education for Appreciating the Environment – An Example of Curriculum Design of Natural Aesthetic Education in Taiwan.[viii] Both approaches are important, but I suspect that the latter are the most effective, because they appeal to the emotional and spiritual side of student’s lives. In the context of mainland China, the many eco-villages provide an excellent context for such education, as do the Whiteheadian kindergartens in Beijing.

These three forms of education – CE, ESL, and EA – are very important if citizens of a given nation are to build and sustain nurturing societies. Without them, ecological civilizations have little chance of evolving. With them, there is hope,

A Wide Soul Embodies the Four Harmonies

So what, then, is the ultimate aim of moral education in an ecological civilization? I suggest that it is to becoming fully human in a way that includes, rather than excludes, the more than human world. The aim is to become an eco-person or, as constructive postmodernists might put it, become a person with a wide soul. This can be put in a uniquely Chinese, neo-Confucian way. A wide soul embodies the four harmonies of which Zhang Zai (1020-1077) speaks in his short article of 253 characters, called the Western Inscription. Zhang Zai speaks of four kinds of harmony with self, harmony with others, harmony with the earth, and harmony with heaven. [ix] The aim of moral education in an ecological civilization is for people to embody and enjoy these four harmonies, each in his or her own way. In so doing they become, as it were, eco-persons or wide souls.

An eco-person is not a cog in a machine or product of social engineering. He or she is an individual with agency of her own who lives simply, graciously, lovingly, and wisely, with a sense of respect for live and environment, other humans much included. She has, as it were, a wide soul.

I borrow the concept of a wide soul from an early process philosopher, Bernard Loomer. In an essay in 1972 he described a sizeable soul as follows:

By S-I-Z-E I mean the stature of [your] soul, the range and depth of [your] love, [your] capacity for relationships. I mean the volume of life you can take into your being and still maintain your integrity and individuality, the intensity and variety of outlook you can entertain in the unity of your being without feeling defensive or insecure. I mean the strength of your spirit to encourage others to become freer in the development of their diversity and uniqueness. I mean the power to sustain more complex and enriching tensions. I mean the magnanimity of concern to provide conditions that enable others to increase in stature." (Bernard Loomer)[x]

Loomer’s paragraph is rich in its meanings and has influenced many process philosophers. But, in light of our need for ecological civilizations, we need to add two more characteristics to the concept that are not evident in Loomer’s paragraph.

First, we best add ecological consciousness or, perhaps better, ecological appreciation. The width of a “wide soul” includes other people, to be sure, especially the poor and powerless. But its width – its horizons of respect, care, identity, and appreciation – also includes the more than human world. As an eco-person, a wide soul feels connected with plants and animals, hills and rivers, trees and stars, knowing that they, too, form part of who and what she is. She knows that she is inwardly composed, not only of her personal past and her relations with friends and family, but also of the air she breathes, the food she eats, the ground she walks on, the sky above. She is what Kevin Clark calls an eco-self.

Second, we might also add what we might call faith or hope; or trust in the availability of fresh possibilities. A wide soul knows that she lives within a universe of continuous creativity (chi) and that, no matter what the struggles of the past, new possibilities blossom forth from the universe itself, such that she can live with a spirit of faith, hope, and adventure. She is not naïve; she knows that the world contains much tragedy, too much of it human-induced. But she is also hopeful, not resigning herself to fate or to the will of an all-powerful deity. She feels what the western poet Gerard Manley Hopkins called a “freshness deep down” within the depths of life, and she tries to live freely and hopefully, a best she can, from this freshness.

If we add these two ideas to what Loomer says in his paragraph, we have what we might call eight characteristics of a wide soul or eco-person.

I suggest, then, that these are the traits of character which need to be encouraged among citizens of an ecological civilization, if they are to help build and sustain communities of respect and care. Without a citizenry that embodies meaningful degrees of these traits, there can be no ecological civilization.

Conclusion

The act of becoming fully human is a lifelong process that begins in childhood and extends into old age. Always we are learning how to be human, and often we make mistakes. Still the ideal of becoming fully human is a worthy ideal and, for that matter, a deeply Confucian ideal, even as it has many parallels in other cultural traditions. It can be facilitated by four kinds of education: Parental Education, Compassion Education, Spiritual Literacy, and Education in Environmental Appreciate. All can help a person grow in his or her capacities to become an eco-person with a wide soul. All can help a person build and sustain a nurturing society.

Of course the goal of becoming an eco-person cannot and should not be homogenizing. There will be many kinds of eco-persons – as many as there are people. Their ranks will include extroverts, introverts, laborers, clerks, teenagers, grandparents, religious people and non-religious people. Each person can become an eco-person in his or her unique way. Amid their differences, they will share a desire to build communities of respect and care for the community of life. And with their lives nourished by the four kinds of moral education identified in this essay, their desires just may be realized.

An ecological civilization is a nurturing society. Its citizens live with respect and care for one another and the larger community of life. A society of this kind requires for four kinds of moral education: family life education, compassion education, education in spiritual literacy, and education in environmental appreciation. These four kinds of education can help people become eco-persons with wide souls, each in his or her own way. He or she lives with a spirit of respect and care, enjoying a modicum of what the Four Harmonies identified by Zhang Zhai (1020-1077) in the Western Inscription: harmony with self, harmony with other people, harmony with the natural world, and harmony with heaven. This paper introduces these kinds of education and further develops the idea of an eco-person with a wide soul. It offers a suggestion of what constructively postmodern moral education might look like.

Essay

An ecological civilization is easy to imagine and hard to realize. It consists of communities that are creative, compassionate, participatory, culturally diverse, humane to animals, ecologically wise, and spiritually satisfying – with no one left behind. Their citizens live with respect and care for the community of life and one another. They listen to one another and feel listened to, knowing that every voice counts. They belong to, and help create, what scholars have come to call a nurturing society.

The Nurturing Society

A nurturing society is a society oriented toward nurturance rather than domination, mutual support rather than hyper-competition, persuasion rather than coercion. Its citizens understand themselves as individuals, but they do not fall into a cult of individualism. They are faithful to the bonds of relationship: relationships with friends and family, to be sure, but also to neighbors and strangers, and of course to the natural world as well. The hills and rivers, the trees and stars – they, too, are their friends. They are what Zhihe Wang and Meijun Fan call eco-persons; they possess what process philosophers call wide souls. Their approach to life helps build and sustain nurturing societies -- the kind of society encouraged by constructive postmodern thinkers around the world, including those in China.

How might we grow toward this kind of society? Many of us in the constructive postmodern tradition emphasize the importance of worldviews in approximating this kind of society. We see the world as a communion of subjects, not a collection of objects, and we believe that seeing the world this way can help us live more lightly on the earth and gently with one another. We talk about a universe which is filled with mutual becoming and intrinsic value, and about the priority of persuasive power over coercive power. We propose that the universe carries within it a normative dimension: a lure toward truth and goodness and beauty, toward wisdom and compassion and creativity. We recognize that many worldviews can point in this direction, but we are especially impressed with that of Alfred North Whitehead, because he helps us understand how such an organic worldview can be both scientific and spiritual, neither to the exclusion of the other.

But our focus on worldview can be overly abstract and short-sighted if it fails to attend to on-the-ground, empirical realities. One of them, for example, is family life. Today, a vast range of research literature from psychology, cognitive linguistics, and political science shows that the emergence of a nurturing society is closely connected with parenting styles in early childhood.

Nurturing parenting styles are neither overly permissive nor overly authoritarian. They combine loving support with discipline, affection with authority. The children of such parents typically feel listened to and respected as they are willing to receive instructions and constructive criticism. In a word, they feel loved. Children with nurturing parents grow up combining pro-social traits such as friendliness, a capacity for listening, and an ability to cooperate with others with individualized traits such as a capacity to think for themselves, take initiative, and act independently. They are the kinds of people who can build and help sustain ecological civilizations.

The alternative parenting style is authoritarian. Here a distinction is important between authoritative, which is good, and authoritarian, which is problematic. The nurturing parenting style is authoritative; the nurturing parent has authority over his or her children. Some scholars speak of the nurturing style as authoritative because the parent exercises what we constructive postmodernists call persuasive or relational power, which is itself, in our view, much more powerful in the long run than coercive or unilateral power. But being authoritative in this persuasive way is very different from being authoritarian.

Authoritarian parenting style exercises its authority in a dominating and unilateral way, such that only one voice has power: that of the parent. The authoritarian parent relies on a threat of punishment, does not listen to his or her child, and emphasizes the primacy of order in the household over spontaneity and love. The results are problematic for the child. As John Sanders explains: “Children raised in strongly Authoritarian families are less able to chart their own moral course (they need someone to tell them what to do in new situations), have less of a conscience (they need an external moral guide), are less respectful of those who are different, and have less ability to resist temptations.[i]

These parenting styles carry over into all aspects of society. Educators and coaches, government officials and employers, can embody nurturing or authoritarian leadership styles. Moreover, these styles may in turn appeal to different people relative to the type of parenting style they had as children. In the United States, for example, one citizen may prefer the “strong” leader whose dominant mode of operation is a promise of restoring order by means of strict laws, whereas another citizen may prefer the “nurturing” leader whose mode of operation includes wise guidance, combined with listening and care.

Studies show as well that these two styles – the nurturing and the authoritarian – obtain in different kinds of societies as well. Again, in the words of John Sanders: “These results do not depend on social or racial background or the marital status of the parents. Furthermore, studies show the nurturing approach superior in countries around the world including China, Australia, Pakistan, and Argentina to name but a few. This is important because these counties are quite diverse in many significant respects. For example, some are collectivist while others are individualist cultures. Yet, the nurturing style is superior in these cultures as well. Studies also show that highly effective educators, coaches, and administrators use the nurturing approach. Children raised by nurturing parents and educators exhibit greater degrees of self-reliance, prosocial behavior, confidence in social settings, motivation to achieve, cheerfulness, self-control, and less substance abuse.”[ii]

Family Life Education

Needless to say, many parents and coaches, government officials and educators combine these styles. They are authoritarian in some contexts, and nurturing in other contexts. Or they send mixed signals. Nevertheless, the nurturing approach is by all means preferred by constructive postmodernists, and they – we – believe that the very future of the planet partly depends on it being prioritized in government, education, public policy as well as family life. We want to nurture the nurturing approach.

The research noted above suggests that much of this nurturance must occur at home and begin in early childhood. In social contexts where families have fallen apart, where parents are absent, or where the home atmosphere is primarily cold and disciplinarian, this kind of nurturance will not occur. One thing that a wise government can do is to develop and provide opportunities for parental training, with specific focus on how to be a nurturing parent.

The training must itself be nurturing. Parents and grandparents must feel empowered, not demeaned, as they shift from an authoritarian to a nurturing mode. And they must learn by seeing examples of the nurturing style, not simply by slogans about the virtues of nurturance. And yet parental training is not enough. In addition to training parents, citizens need to be trained about how to approach the larger society and the natural world in nurturing ways. This can best occur through moral education in public schools. [iii] By moral education I do not mean training in ethics alone. I mean training in what it means be a whole person. Three kinds of moral education are especially important.

Compassion Education, Education for Emotional/Spiritual Literacy,

And Education for Environmental Appreciation

.

The first is Compassion Education (CE): educating people in practical ways to expand their capacities for respect and care. In the United States three research centers especially promising in this regard: Stanford University’s Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education,[iv] the Center for Mindfulness Studies in Toronto, Canada[v]; and the Claremont Center for Engaged Compassion.[vi] As the Stanford center makes clear, organizations ground their work in leading-edge scientific research: brain-mind and behavior studies, clinical psychology studies, and biomedical studies. The Claremont Center trains facilitators and does “compassion work” all over the world through what it calls the Pulse Method. I offer an excerpt in Appendix A.

The second is Education for Spiritual Literacy (ESL): that is, educating people to recognize the spiritual side of their lives and the spiritual side of other people’s lives, so that they can treat themselves and other people as whole persons: that is, persons with inner capacities for curiosity and wonder, for imagination and listening, as well as for kindness and compassion. Here spirituality does not refer to religious affiliation. It refers instead to the moods and modalities found in the circle below, developed by Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat in Claremont, CA. In their wheel of spirituality they offer a vocabulary, a spiritual alphabet, for appreciating the positive emotions that people seek and feel in daily life, and which are part of what it means to be a whole person.

Spiritual literacy is closely connected to emotional intelligence. In the latter regard the pioneering work of the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence is especially important.[vii] This center trains teachers throughout the United States to help children grow in emotional intelligence: knowing and managing their own emotions, understanding the emotions of others. Insofar as moral education includes education in spiritual literacy, it simultaneously included education in emotional intelligence: that is, in recognizing positive emotions in oneself and others.

The third is education for Environmental Appreciation (EA): educating people about the more-than-human world (the hills and rivers, plants and animals) and providing them with opportunities to appreciate that world, in its beauty and intrinsic value (value independent of its usefulness to human beings.) There are many examples of such education around the world and often they rely two models: a cognitive model and an aesthetic model. In the words of Chung-Ping Yang: “The former stresses the necessity of scientific knowledge, including ecology, biology, and geography, while the latter focuses more on imagination, intuition, mystery, and folktales.” See Yang’s Education for Appreciating the Environment – An Example of Curriculum Design of Natural Aesthetic Education in Taiwan.[viii] Both approaches are important, but I suspect that the latter are the most effective, because they appeal to the emotional and spiritual side of student’s lives. In the context of mainland China, the many eco-villages provide an excellent context for such education, as do the Whiteheadian kindergartens in Beijing.

These three forms of education – CE, ESL, and EA – are very important if citizens of a given nation are to build and sustain nurturing societies. Without them, ecological civilizations have little chance of evolving. With them, there is hope,

A Wide Soul Embodies the Four Harmonies

So what, then, is the ultimate aim of moral education in an ecological civilization? I suggest that it is to becoming fully human in a way that includes, rather than excludes, the more than human world. The aim is to become an eco-person or, as constructive postmodernists might put it, become a person with a wide soul. This can be put in a uniquely Chinese, neo-Confucian way. A wide soul embodies the four harmonies of which Zhang Zai (1020-1077) speaks in his short article of 253 characters, called the Western Inscription. Zhang Zai speaks of four kinds of harmony with self, harmony with others, harmony with the earth, and harmony with heaven. [ix] The aim of moral education in an ecological civilization is for people to embody and enjoy these four harmonies, each in his or her own way. In so doing they become, as it were, eco-persons or wide souls.

An eco-person is not a cog in a machine or product of social engineering. He or she is an individual with agency of her own who lives simply, graciously, lovingly, and wisely, with a sense of respect for live and environment, other humans much included. She has, as it were, a wide soul.

I borrow the concept of a wide soul from an early process philosopher, Bernard Loomer. In an essay in 1972 he described a sizeable soul as follows:

By S-I-Z-E I mean the stature of [your] soul, the range and depth of [your] love, [your] capacity for relationships. I mean the volume of life you can take into your being and still maintain your integrity and individuality, the intensity and variety of outlook you can entertain in the unity of your being without feeling defensive or insecure. I mean the strength of your spirit to encourage others to become freer in the development of their diversity and uniqueness. I mean the power to sustain more complex and enriching tensions. I mean the magnanimity of concern to provide conditions that enable others to increase in stature." (Bernard Loomer)[x]

Loomer’s paragraph is rich in its meanings and has influenced many process philosophers. But, in light of our need for ecological civilizations, we need to add two more characteristics to the concept that are not evident in Loomer’s paragraph.

First, we best add ecological consciousness or, perhaps better, ecological appreciation. The width of a “wide soul” includes other people, to be sure, especially the poor and powerless. But its width – its horizons of respect, care, identity, and appreciation – also includes the more than human world. As an eco-person, a wide soul feels connected with plants and animals, hills and rivers, trees and stars, knowing that they, too, form part of who and what she is. She knows that she is inwardly composed, not only of her personal past and her relations with friends and family, but also of the air she breathes, the food she eats, the ground she walks on, the sky above. She is what Kevin Clark calls an eco-self.

Second, we might also add what we might call faith or hope; or trust in the availability of fresh possibilities. A wide soul knows that she lives within a universe of continuous creativity (chi) and that, no matter what the struggles of the past, new possibilities blossom forth from the universe itself, such that she can live with a spirit of faith, hope, and adventure. She is not naïve; she knows that the world contains much tragedy, too much of it human-induced. But she is also hopeful, not resigning herself to fate or to the will of an all-powerful deity. She feels what the western poet Gerard Manley Hopkins called a “freshness deep down” within the depths of life, and she tries to live freely and hopefully, a best she can, from this freshness.

If we add these two ideas to what Loomer says in his paragraph, we have what we might call eight characteristics of a wide soul or eco-person.

- a capacity for loving relationships with other people, including friends and family, and also including those who are otherwise vulnerable: the forsaken, the forgotten, the downtrodden.

- an open mind that can entertain new ideas without being defensive or insecure.

- a desire for harmony, but also capacity to live with enriching tensions, even when they cannot be resolved, realizing that differences make the whole richer.

- a sense of individuality, a recognition of personal worth, a capacity to stand by principle

- a capacity to accept complexity without reducing things to either-or, a capacity for both-and thinking.

- a willingness to encourage others in constructive ways, meeting them where they are and helping them grow toward width of soul in their own unique ways.

- a strong sense of connection with the more than human world -- the hills and rivers, the trees and stars – cognizant that we humans are small but included in a larger web of life.

- a sense that the universe itself is a creative process, slightly new at every moment, replete with fresh possibilities not reducible to fate.

I suggest, then, that these are the traits of character which need to be encouraged among citizens of an ecological civilization, if they are to help build and sustain communities of respect and care. Without a citizenry that embodies meaningful degrees of these traits, there can be no ecological civilization.

Conclusion

The act of becoming fully human is a lifelong process that begins in childhood and extends into old age. Always we are learning how to be human, and often we make mistakes. Still the ideal of becoming fully human is a worthy ideal and, for that matter, a deeply Confucian ideal, even as it has many parallels in other cultural traditions. It can be facilitated by four kinds of education: Parental Education, Compassion Education, Spiritual Literacy, and Education in Environmental Appreciate. All can help a person grow in his or her capacities to become an eco-person with a wide soul. All can help a person build and sustain a nurturing society.

Of course the goal of becoming an eco-person cannot and should not be homogenizing. There will be many kinds of eco-persons – as many as there are people. Their ranks will include extroverts, introverts, laborers, clerks, teenagers, grandparents, religious people and non-religious people. Each person can become an eco-person in his or her unique way. Amid their differences, they will share a desire to build communities of respect and care for the community of life. And with their lives nourished by the four kinds of moral education identified in this essay, their desires just may be realized.

Education in Spiritual Literacy

In an Ecological Civilization, it is very important to be spiritually literate and emotionally intelligent. A person can be non-religious and have a spiritual side to his or her life, A person can be “scientific” and have a spiritual side to his or her life. Spirituality is the emotional intelligence that holds families together giving hope and joy to individuals and communities, even in times of tragedy and difficulty.