- Home

- Process Worldview

- Community

- Art and Music

- Whitehead and Process Thinking

- Podcasts

- Spirituality

- Ecological Civilization

- Education

- Contact

- Social Justice

- Science

- Animals

- Sacred Poems

- Whitehead Videos

- Index of All Titles

- Practicing Process Thought

- Process Spirituality: A Spiritual Alphabet

- Recent Posts

What is Creativity? What is God?

as you read Whitehead's Process and Reality

- Creativity is pure activity, equally expressed in beauty and horror, love and cruelty, peace and violence, injustice and justice. It is always happening, always advancing into novelty.

- Creativity can be named in different ways. It is analogous to what Buddhists call sunyata or emptiness. Some mystics may speak of it as the godhead. It is entirely beyond good and evil and has no preferences. It is that of which all things are expressions.

- Creative transformation is positive, life-enhancing creativity. It is expressed in beauty, love, peace, and justice.

- All creatures, not just God, are expressions of creativity. God is instead the primordial expression of creativity giving it a positive character: an all-inclusive Life, embracing the universe, in whose consciousness and care the universe unfolds.

- God is a catalyst for creative transformation. Whereas human beings might awaken to creativity; they place their deepest trust in God. God is love.

- God and Creativity are not competitive. Creativity is the ultimate reality. God is the ultimate actuality. Different religions may orient themselves around one or the other, but it is also possible, along with Whitehead, to recognize the truth of both.

Creativity as Ultimate

Open to all and without character of its own,

it is completely neutral morally. It is activity itself.

John Cobb writes:

“Concrescence” focuses attention on the inner dynamics of the becoming of a single occasion. It presupposes that there have been other occasions and that there will be new ones in the future. “Creativity” directs attention equally to concrescence and transition. At every instant the many, the vast many, are becoming one in a myriad of occasions. The becoming of each of these occasions adds a new one to that myriad. Whereas “concrescence” focuses on the individual subjective act of becoming, “creativity” draws attention to the ever ongoing process through which the cosmos continues in being. It is the way of denoting the ultimate fact that “the many become one and are increased by one.”

Whitehead identifies creativity as “the ultimate.” It is that of which every actual entity is an instance. It plays the role in Whitehead that “being itself” plays in the Thomistic tradition. In that tradition to be is to be an instance of being. In Whitehead to be actual is to be an instance of creativity. In Thomism being itself is beyond all attributes or characteristics. In Whitehead, likewise, creativity has no character of its own, in the sense that it is open equally to any and all eternal objects and is in itself characterized by none.

Using different labels for what is ultimate does not in itself determine that there are metaphysical differences. Thomas identified “being itself” as the “act of being.” One could regard Whitehead’s work as explaining what an act of being is, i.e., the unification of the many. Thomism may not be closed to that possibility. However, the term “being itself” easily suggests something more static and substantial, that is, something underlying all diversity and particularity. In some formulations it seems that being itself might even exist without embodiment in particular instantiations. “The many becoming one” cannot underlie anything and certainly cannot exist or occur except in particular instances. It may be that the discussion of what is ultimate has played a larger role in India than in the West. Brahman is the traditional Hindu ultimate and is very much like being itself. Buddhists found the understanding of Brahman to be substantialist, and they rejected it. In one important form of Buddhism, they affirmed instead that everything is an instance of pratitya samutpada or dependent origination. The similarity to Whitehead’s creativity is striking.

Whitehead’s own comparisons are with the “neutral stuff” affirmed by some of his contemporaries and with the ‘prime matter” of the Aristotelian tradition. In other words, by the “ultimate” he means that of which all things consist. It is the ultimate “material cause” in Aristotle’s sense. But for Whitehead the “material cause” is definitely not matter. Metaphysically, and in physics as well, “matter” is fundamentally passive. For Whitehead, creativity could be thought of as activity itself. It is closer to what physicists mean by energy than what is connoted when they speak of matter.

*

Sometimes the reader of Whitehead is likely to project into “creativity” more than he intends. Whitehead does cause us to marvel that whatever happens, the process of bringing new occasions out of old ones continues. Creation is fundamental and ongoing. There is always something new. But what is new may not be better than what is old. Occasions that occur in the process of the decay and dying of larger organisms, such as human beings, are also instances of creativity, no more and no less than those that bring new life into being. Creativity is completely neutral from a moral perspective. Mutual slaughter consists in instances of creativity just as does the composition of a symphony. Also one cannot speak of more and less creativity. Like ultimates in other traditions, creativity is beyond good and evil or any quantification.

Cobb Jr, John B. Whitehead Word Book: A Glossary with Alphabetical Index to Technical Terms in Process and Reality (Toward Ecological Civilization Book 8) . Process Century Press. Kindle Edition.

Whereas Creativity is Morally Neutral

Creative Transformation is Positive, Life-Enhancing Creativity

Jay McDaniel

An astronomer and flute player are talking about how they see the world. The astronomer says “I see the world

as a creative process that began with a big bang and is unfolding through time in a creative and exploratory way.”

The flute player says “I see the world in exactly the same way, and I try to play the flute as a way of collaborating

with the creativity of the wind and hills and rivers.”

They go to a museum and see a Chinese landscape painting. Beneath the painting there is a description of the

landscape. The description says: “The hills and rivers, trees and stars are all expressions of a continuous creativity

called qi(气).” The astronomer says “I study the mathematical properties of qi(气).” The flute player

says “I play the musical qualities of qi(气).” They go drink tea together and note that the tea, too, contains qi(气)

This is how Whitehead, steeped in the sciences and the humanities, looks at the world. He sees the world as

inherently creative. He thinks science focuses on the mathematical properties of a continuously creative universe

and the humanities on the axiological or value-laden qualities of the universe. In order to understand this point of

view, let’s consider two realities: creativity and creative transformation.

Creativity

What is creativity? Perhaps it’s best to ask where creativity is.

Creativity is in the subjectivity of each and every human being as she responds to the circumstances of her life,

moment by moment.

Creativity is in the subjectivity of every other living being - each animal, each living cell – as it responds to the

circumstances of its life.

Creativity is in the activity by which a single pulsation of energy within the depths of an atom – a momentary

quantum event within an electron, for example – responds to the conditions which precede its occurrence. It is

the spontaneity of the quantum event itself, to which (so Whiteheadians believe) quantum theory points. This is

how they interpret the principle of indeterminacy. We live in a universe in which the future is not yet decided.

Creativity is in the subjectivity of the supreme being whom Whitehead names “God” in Process and Reality and

which he calls “Peace” in Adventures of Ideas, as this subjectivity gathers each event in the universe into an

everlasting and fluid act of concrescence.

Creativity is also in emergence of new events in the ongoing history of the universe, which occurs every time

there is a perishing of immediacy in the old events. For example, as you are now reading these words, the

event of getting up in the morning, which occurred earlier in the day, has now perished, making way for this

act of reading. This is happening all the time and everywhere. Something new comes after something old has

passed away.

Creativity is in the differences between things: the way in which each entity in the universe asserts itself as being

this rather than that, even as it is connected to every other entity in a network of inter-being. This act of self-assertion is not vain or arrogant; it is simply the entity being what it is, in the moment: an individualized

concrescence of the universe.

It is important to note that creativity as described above is neither good nor evil. It is what philosophers call

ontological creativity. Ontological simply means “related to the existence or being of things.” The new event that

takes the place of older events may be quite tragic. Things can get worse rather than better, less just and more

unjust, less peaceful and more violent. The subjective response of a person to her environment may be filled

with hatred, or confusion, or sadness. The living cell with its creativity may be cancerous and thus destructive to

the life of the person it inhabits. But the creativity is creativity.

We sometimes call this creativity a person’s freedom. Here freedom is not necessarily a positive word, just a

descriptive term. His freedom is the act of decision which occurs moment by moment, amid which one possibility

is cut off and another actualized. Imagine a man climbing a mountain, and he must choose, moment by moment,

where to step. As he steps on one rock, he automatically cuts off, at that moment, the possibility of stepping on

the other. He creates a single action and becomes that action in that moment. Yes, the particular step he takes

is preceded by many other steps, and he may be in the habit of always stepping on a certain kind of rock. But in

the moment of stepping there is a decision to be made. This decision is his creativity.

In Whitehead’s philosophy this kind of creativity is not necessarily conscious. When we drive a car from one

location to another, pressing our foot against the gas pedal and then the brake, we are making decisions all the

time. But most of them are pre-conscious and habitual. The same goes for walking. Whiteheadians believe

that this kind of decision-making is found within other animals, too. As a fox chases a rabbit, it makes decisions

where to run. It is from this creativity that the differences in our world emerge, whether happy or sad. A violent

mob is creative, and so is a peaceful group of monks. Creativity in this sense is the sheer happening of what

happens, as it happens, moment by moment. It is the becoming of what is becoming.

Whiteheadian philosophers in the East and West speak of this creativity as the Brahman of which the Upanishads

sometimes speak, and as the Tao of which Taoism sometimes speak. And the qi of which Chinese medicine

sometimes speak. Or, to put it differently, these diverse traditions illuminate different aspects of, and deepen, our

understanding of creativity. There is not a single word to name the happening of what happens in its newness,

moment by moment. But everywhere we look we see it.

Understood in this sense, creativity is life itself. Imagine a Chinese landscape painting. You see hills and rivers,

trees and stars, rivers and mountains, and in one corner a small village with people in it. You see a man fishing

on a boat. From Whitehead’s perspective all are expressions of creativity. It is the essence of the Ten Thousand

Things.

Creative Transformation

In addition to the creativity just described, there is another kind of creativity that is important in human life.

Whiteheadians call it creative transformation. We might also call it constructive creativity or harmonious creativity.

Creative transformation is the kind of creativity that occurs when people are open to fresh possibilities for harmony

and intensity in their lives, when these fresh possibilities, as actualized, create mutually enhancing bonds with

other people. These mutually enhancing bonds are what, in East Asian traditions, people call harmony.

Again it is best to ask where we see it. We see it in a language student when she enjoys the intensity of learning

a new language and having her mental and spiritual horizons expanded. We see it in a wise old grandfather who,

in the face of hardships in his life, has somehow managed to face the world with grace and true grit. We see it in

a young woman who experiments with making Korean bibimbap in fresh ways, or simply repeats a recipe she

learned from her mother in joyful ways. We see it in a student who enjoys the thrill of discovery in the sciences,

and becomes a physicist or engineer. We see it in another woman who volunteers her time to help orphans.

And in a student who has the courage to be honest about the difficulties he faced in high school.

We also see this kind of creativity can also be found in the business world, when entrepreneurs use their

business skills, not just to make money, but to help the world as best they can. And we see it in people who

resist the injustices of the world, and speak truth to power, like Martin Luther King Jr. In all of these kinds of

creativity there is change or transformation, and something good emerges from the change. Indeed goodness

might be another name for this creativity, all the while realizing that goodness is a process – an activity – and not

a static state of affairs.

For many Whiteheadians the love at the heart of the universe – “God” or “Peace” – is the internal catalyst for this

kind of healthy creativity, this kind of goodness. We find “God” in the goodness itself, as it unfolds in human life,

and also as the lure toward goodness within human life, which is often expressed as a lure toward wisdom and

compassion.

Related to this kind of healthy creativity is also the subjective sense of curiosity or wonder. They are, as it were,

the symptoms or subjective side of creativity. Thus the purpose of education at its best is to help students

discover this kind of curiosity and wonder and then channel it in constructive directions that benefit themselves

and the whole of society. Education should be in service to this kind of creativity: in service to creative

transformation. In Vivian Dong’s essay on Learning to Love Science we see the role that teachers can play in

education, if given the chance. Of course most teachers want to foster this kind of creativity, but face various

constraints in what they can do, given the size of their classes and the demands they face. This is why so many

Whiteheadians are interested in educational reform.

Also related to this kind of healthy creativity is the simple ability to make the best of a bad situation: to make

“lemonade from lemons.” It goes without saying that for many people in our world, life is filled with suffering and

hardship. Every day, every moment, the best they can do is to have courage and turn misfortune into something

creative. High school students who face terrible pressures to succeed must do this; older people who face death

must do this. For people who are seriously depressed, just getting out of bed in the morning is an achievement.

This, too, is creative transformation.

Still another important form of creative transformation is play. As Nietzsche points out, there is something deeply

important – something beautiful – about having a playful and exploratory mind, a flexible and jazzlike mind. This

kind of mind has a certain joy inside it: a love of life. The capacity for having this love of life begins with

childhood, when parents give their children opportunities for unstructured play and when, in addition, they join

them in playing games together. In the mutuality of play, there is the beginning of a creative life. Playfulness then

becomes a habit, which helps a person make it through the most difficult of times. One of the most glorious

expressions of this playfulness is a sense of humor. Humor is a form of creativity, too.

Constructive chaos is a form of creativity, too. We see it in human life when, as life becomes too habitual and

too stale, old habits must be broken in order for new things to emerge. Too much order is the enemy of creativity;

and so is too much chaos. Constructive chaos is that place in between too much order and too much chaos

where improvisation occurs. We see this, for example, in music when artists take an existing piece and do

something creative with it, and also when they experiment with forms of music that may seem chaotic, but that

are making space for new possibilities. And we see it when an educator throws away her game plan and tries

something new in the classroom. Even if her experiment fails, there is something good in the experimentation

itself.

At their best the cultural and religious traditions of the world offer guidelines for creative transformation. At their

worst, they offer obstacles to creative transformation. In China, for example, the May Fourth movement of the

1920’s was an attempt to throw away the cultural traditions of the past and move into something new. The

impulse is understandable but the method was problematic. Genuine creative transformation at a cultural level

occurs when people build upon the wisdom of their past but also enjoy the experiment of being open to new

possibilities. It is sometimes said that a good parent provide children with roots and wings. Cultures need roots

and wings, too. In the very activity of building upon the best of the past there is creativity of the healthy kind; and

in the activity of being open to new possibilities there is also creativity. The aim of creativity in both instances is

harmonious creativity – the fullness of life – moment by moment.

God is an Everlasting Catalyst for, and

Companion to, Life-Enhancing Creativity

In Whitehead's philosophy God is not the ultimate. The ultimate is the pure activity of which all things are expressions. It has no preferences or aims. It is morally neutral. It is equally expressed in all things: God, a puff of energy, a moment of human experience, an act love, an act of cruelty. Wherever there is activity of any kind there is creativity. John Cobb puts it this way.

God is not the “ultimate.” God is an instance of creativity. God does not control what happens. There are many “reasons” for what happens in every event, of which God is always only one; that is God never unilaterally determines what happens. Still God is always one of these reasons, the one who calls for the realization of optimum value and makes that realization possible.

God is the supreme instance of this creativity, indeed the primordial or eternal instance; but not the only instance.

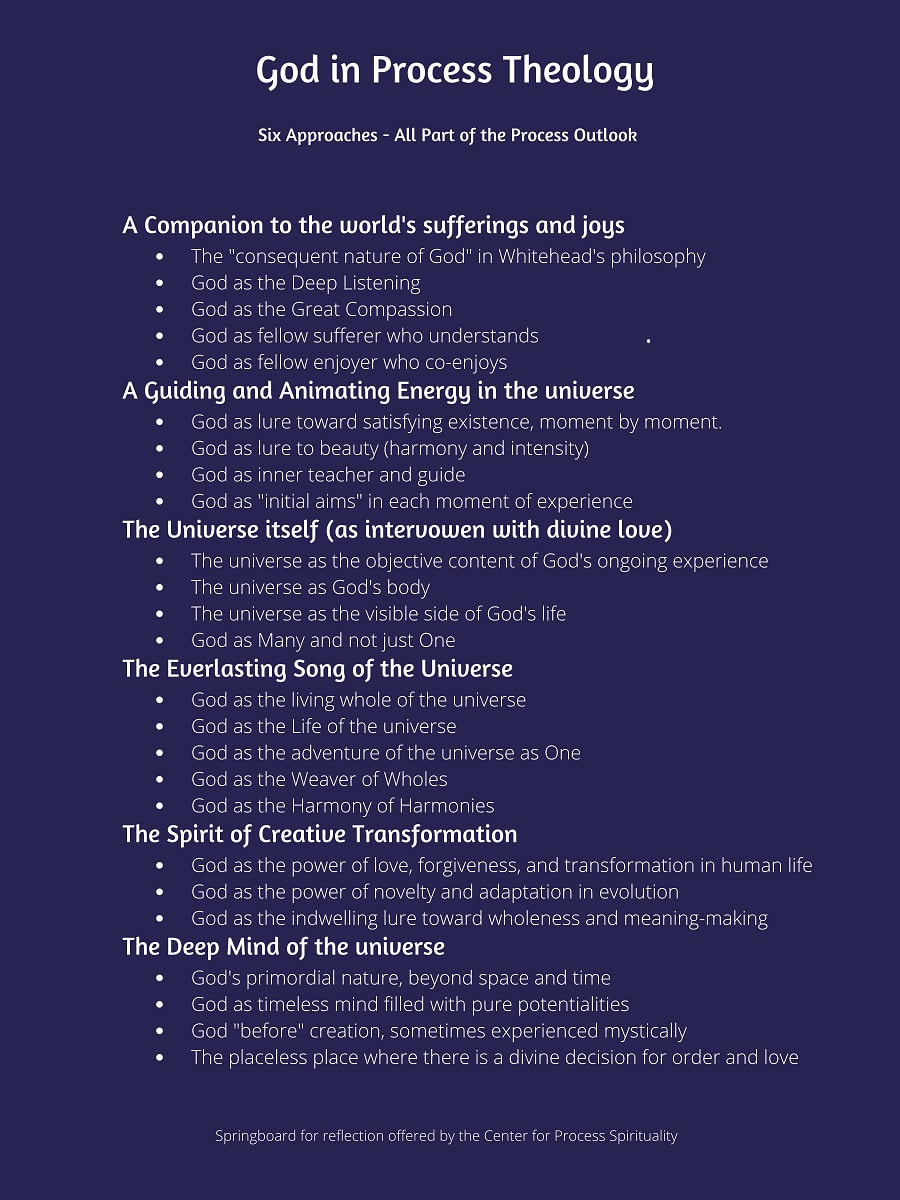

John Cobb proposes that God is ultimately important as the subject of faith or trust, as a catalyst for creative transformation, as an eternal companion to the world's sufferings and joys, as love. As distinct from creativity, God has aims and preferences. God 'feels' or 'experiences' things. Here are ten ways of thinking about God, none of which would apply to creativity.

God is not the “ultimate.” God is an instance of creativity. God does not control what happens. There are many “reasons” for what happens in every event, of which God is always only one; that is God never unilaterally determines what happens. Still God is always one of these reasons, the one who calls for the realization of optimum value and makes that realization possible.

God is the supreme instance of this creativity, indeed the primordial or eternal instance; but not the only instance.

John Cobb proposes that God is ultimately important as the subject of faith or trust, as a catalyst for creative transformation, as an eternal companion to the world's sufferings and joys, as love. As distinct from creativity, God has aims and preferences. God 'feels' or 'experiences' things. Here are ten ways of thinking about God, none of which would apply to creativity.

1. God's unchanging aim is for beauty understood as richness of experience.

2. God seeks salvation for each and all: universal richness of experience.

3. God is in the world through fresh possibilities or "initial aims."

4. We feel God's feelings and share in God's desires. God is within us.

5. God is both eternal and everlasting: non-temporal and infinitely temporal.

6. God is nowhere and everywhere: non-spatial and omni-spatial.

7. God is lovingly affected by the world: a fellow sufferer who understands.

8. God saves the world through tenderness.

9. God is many as well as one.

10. God recycles love.

2. God seeks salvation for each and all: universal richness of experience.

3. God is in the world through fresh possibilities or "initial aims."

4. We feel God's feelings and share in God's desires. God is within us.

5. God is both eternal and everlasting: non-temporal and infinitely temporal.

6. God is nowhere and everywhere: non-spatial and omni-spatial.

7. God is lovingly affected by the world: a fellow sufferer who understands.

8. God saves the world through tenderness.

9. God is many as well as one.

10. God recycles love.

for more, click here: