I Felt this Loving Presence:

Ten Ways of Knowing Jesus

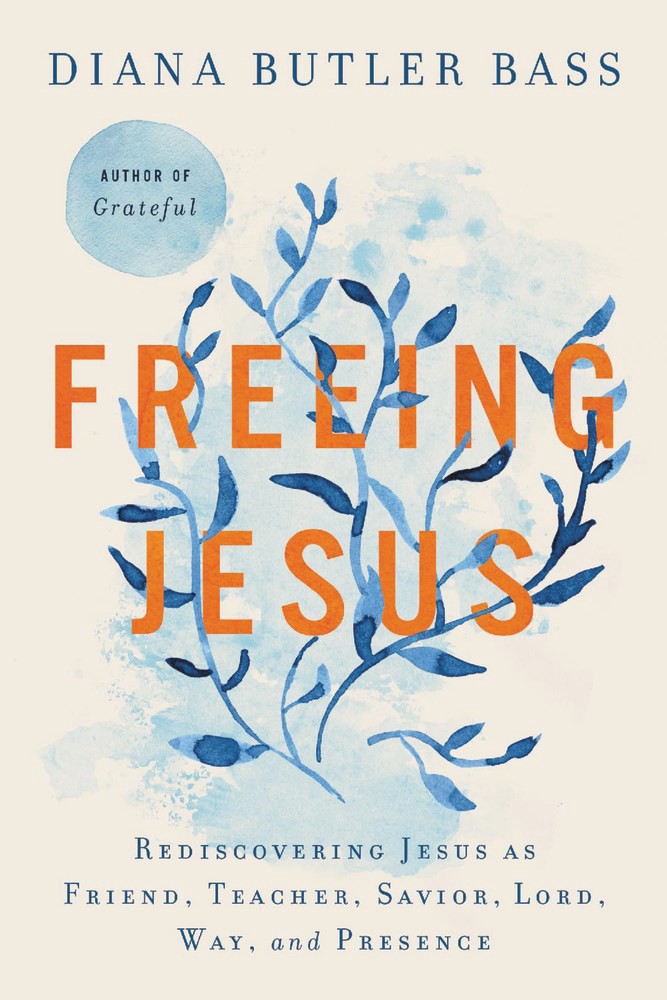

In Process Theology Jesus can be known and loved in ten ways.

Each is a way that Jesus is present in human life.

All make sense from a process perspective.

- a friend in the journey of life,

- a prophet of hope (who comforts the afflicted and afflicts the comfortable)

- a crucified savior,

- a resurrected savior,

- an incarnation of God,

- a living field of force,

- a cosmic spirit (the universal Christ)

- a way of living (filled with truth and life)

- a divine revelation,

- a loving presence in the here-and-now.

Not all of these ways need make sense to everyone. In a person's journey with Jesus, each can be a starting point and many combinations can be meaningful. But all are available.

Not all of these ways need make sense to everyone. In a person's journey with Jesus, each can be a starting point and many combinations can be meaningful. But all are available.

Jesus as a Loving Presence

|

DEAR GOD, Do you cry? Jesus did. He cried when Lazarus died, even though he knew resurrection was coming. It hurt. Do you cry? You created crying—rivers summoned by pain, blurred vision, the washing of cheeks with sorrow. Do you cry? Love, ME

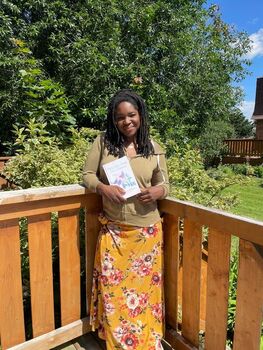

"I was standing out on my patio, and I felt this loving presence behind me. I know that it was Jesus. I felt this love that I had never felt, this kindness that I had never felt. And it was that kindness, knowing that God actually loved me and cared for me, that helped me approach God with honesty. And I think honesty in faith and prayers is what really changes things." - Bunmi Laditan |