The Enjoyment of Holy Envy

and a theology to support it

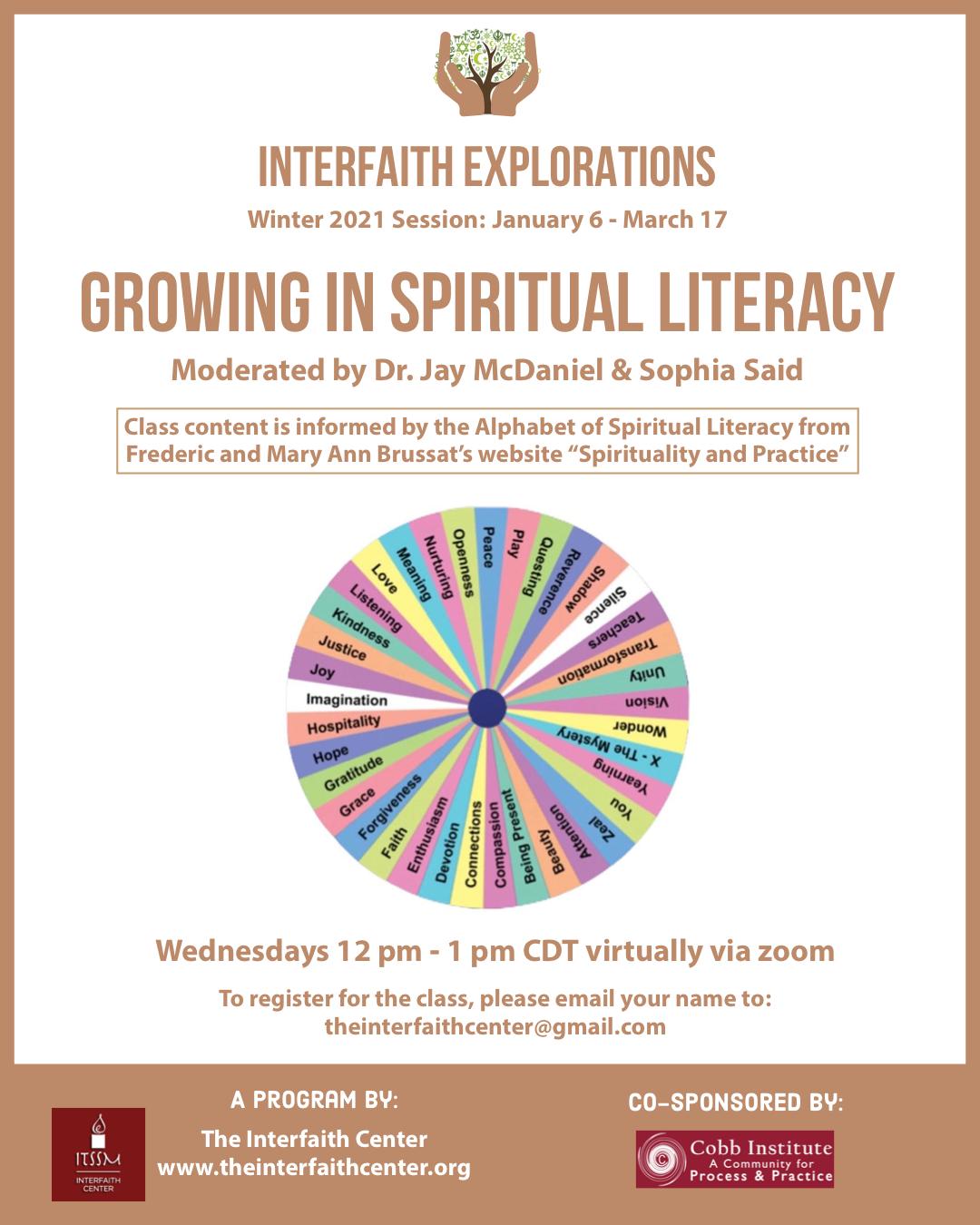

In the spiritual alphabet “T” is for transformation.

Transformation is what happens to you when you see and feel things differently from how you did in the past. You are just a little wiser than you had been, and just a little kinder. You can embrace the creative tensions in life more easily and see life in a different way. You are more open to change and you've become a better listener. In the language of open and relational (process) theology, your soul has grown wider.

*

One place where transformation of this kind happens to many people is in interfaith communities such as the one pictured at the bottom of this page, after the essay by Dr. Paul Ingram.

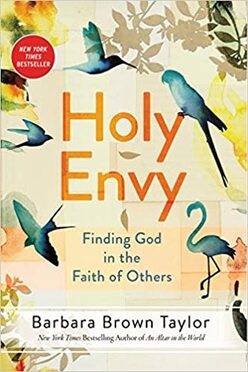

People who are committed to a particular religious path, and who become friends with people of other faiths in interfaith communities, are changed by the relationships. Even as they may love their own religious or spiritual path, albeit with some reservations and criticism; they find something loveable in their friends of other faiths and in their faiths themselves. In the words of Barbara Brown Taylor, they begin to “envy” their friends in a way that is open to being transformed by the wisdom they sense. Call it transformation through holy envy.

Taylor borrows the phrase from biblical scholar Krister Stendahl, who offered three rules for engaging in dialogue with people of other faiths:

In Taylor’s book, holy envy is described in various ways. One aspect of holy envy, she ways, is that is naturally leads to an opening of horizons: that is, to finding a bigger box with more windows. In her words:

“Holy envy may lead you to borrow some things, and you will need a place to put them. You may find spiritual guides outside your box whom you want to make room for, or some neighbors from other faiths who have stopped by for a visit. However it happens, your old box will turn out to be too small for who you have become. You will need a bigger one with more windows in it—something more like a home than a box, perhaps—where you can open the door to all kinds of people without fearing their faith will cancel yours out if you let them in. If things go well, they may invite you to visit them in their homes as well, so that your children can make friends.”

Some people seek a theology for such expansion, a theology for opening horizons. Process theology offers one such theology. It suggests that the practice of holy envy can be guided by these principles.

Transformation is what happens to you when you see and feel things differently from how you did in the past. You are just a little wiser than you had been, and just a little kinder. You can embrace the creative tensions in life more easily and see life in a different way. You are more open to change and you've become a better listener. In the language of open and relational (process) theology, your soul has grown wider.

*

One place where transformation of this kind happens to many people is in interfaith communities such as the one pictured at the bottom of this page, after the essay by Dr. Paul Ingram.

People who are committed to a particular religious path, and who become friends with people of other faiths in interfaith communities, are changed by the relationships. Even as they may love their own religious or spiritual path, albeit with some reservations and criticism; they find something loveable in their friends of other faiths and in their faiths themselves. In the words of Barbara Brown Taylor, they begin to “envy” their friends in a way that is open to being transformed by the wisdom they sense. Call it transformation through holy envy.

Taylor borrows the phrase from biblical scholar Krister Stendahl, who offered three rules for engaging in dialogue with people of other faiths:

- When trying to understand another religion, you should ask the adherents of that religion and not its enemies.

- Don’t compare your best to their worst.

- Leave room for holy envy.

In Taylor’s book, holy envy is described in various ways. One aspect of holy envy, she ways, is that is naturally leads to an opening of horizons: that is, to finding a bigger box with more windows. In her words:

“Holy envy may lead you to borrow some things, and you will need a place to put them. You may find spiritual guides outside your box whom you want to make room for, or some neighbors from other faiths who have stopped by for a visit. However it happens, your old box will turn out to be too small for who you have become. You will need a bigger one with more windows in it—something more like a home than a box, perhaps—where you can open the door to all kinds of people without fearing their faith will cancel yours out if you let them in. If things go well, they may invite you to visit them in their homes as well, so that your children can make friends.”

Some people seek a theology for such expansion, a theology for opening horizons. Process theology offers one such theology. It suggests that the practice of holy envy can be guided by these principles.

Differences make the whole richer.

1. As people from different traditions enter into dialogue and cooperative relations, they can and should bring what is most important to them to the table. They don't have to leave their roots behind. Differences make the whole richer.

We are part of a larger web of life.

2. Interfaith dialogue can include a dialogue with the earth, because human life is nested within, not apart, from the wider web of life. Environmental education and inter-faith dialogue can go hand in hand. All creatures have their own kind of spirituality. Subjectivity goes all the way down.

An essential need today is to build compassionate communities.

3. In an age of global climate change, one aim of interfaith dialogue and cooperation is to help build communities that are creative, compassionate, participatory, multi-religious and ecologically wise, with no one left behind. The common good of the world is not simply community, it is eco-community.

There may be many forms of ultimacy.

4. Different religions may highlight different features of reality as ultimately real (interconnectedness, the primacy of the present moment, the value of community, the reality of spirit worlds, the love of God). For one religion to be right, the others do not need to be wrong. They can be right about different things. The truths are many.

There may be many forms of salvation.

5. There may be different forms of salvation, corresponding to the diverse ultimates. One religion may highlight a form of well-being that emerges through an awakening to interconnectedness, another may highlight a form of well-being that emerges by accepting God's forgiving love, and still another may highlight a form of well-being that finds meaning in concourse with the spirits. Different religions do not need to have the same goals.

Religions are more than worldviews.

6. There is much more to religion than worldviews and beliefs. Religions include community, rituals, images, sounds, hopes, dreams, and stories. Sometimes it is these things -- not the worldviews -- that is most important to people.

We learn by listening.

7. We can bring to interfaith dialogue an appreciation of the role of the arts and music in dialogue, cognizant that, when it comes to knowing the religious other, there are many ways of knowing, including visual and musical and bodily knowing. Prayer and meditation are forms of knowing, too.

We can be transformed by what we hear.

8. One of the aims of dialogue, once trusted relations emerge, is mutual transformation, by which people internalize insights from the other and are transformed in the process.

Our capacities for empathy may be more than we know.

9. Human beings can feel the feelings of other human beings and take on their perspectives, even if they do not have shared histories or common backgrounds.

It's alright to critique one another, too.

10. Once trusted relations emerge, genuine dialogue can include mutual criticism and debate. In genuine dialogue it is alright to say "I disagree." Often we learn more from disagreements than agreements.

Self-critique is extremely important.

11. More important than critiquing others is self-critique. If we absolutize our inherited traditions (ritual and intellectual) and make gods of them, we miss the spirit of creative transformation. We have roots without wings.

We may need to reinvent our religions.

12. Religions are evolving through time, and they are never quire reducible to their inherited patterns and worldviews. Interfaith dialogue and cooperation provide opportunities for the creative development of world religions so they grow less violent, less arrogant, and more hospitable to life.

God is a lure toward dialogue and transformation.

13. The very desire for dialogue and widened horizons comes from a dimension of the universe itself -- a divine yearning -- that is present throughout the world as a spirit of creative transformation.

Interfaith cooperation as practicing the presence of God

14. When we are cooperating with others in respectful ways that help enrich the well-being of life on earth and in local communities, we are practicing the presence of God.

Paul O. Ingram, a theologian and historian of religion, spells out further implications and guidelines in the essay below.

1. As people from different traditions enter into dialogue and cooperative relations, they can and should bring what is most important to them to the table. They don't have to leave their roots behind. Differences make the whole richer.

We are part of a larger web of life.

2. Interfaith dialogue can include a dialogue with the earth, because human life is nested within, not apart, from the wider web of life. Environmental education and inter-faith dialogue can go hand in hand. All creatures have their own kind of spirituality. Subjectivity goes all the way down.

An essential need today is to build compassionate communities.

3. In an age of global climate change, one aim of interfaith dialogue and cooperation is to help build communities that are creative, compassionate, participatory, multi-religious and ecologically wise, with no one left behind. The common good of the world is not simply community, it is eco-community.

There may be many forms of ultimacy.

4. Different religions may highlight different features of reality as ultimately real (interconnectedness, the primacy of the present moment, the value of community, the reality of spirit worlds, the love of God). For one religion to be right, the others do not need to be wrong. They can be right about different things. The truths are many.

There may be many forms of salvation.

5. There may be different forms of salvation, corresponding to the diverse ultimates. One religion may highlight a form of well-being that emerges through an awakening to interconnectedness, another may highlight a form of well-being that emerges by accepting God's forgiving love, and still another may highlight a form of well-being that finds meaning in concourse with the spirits. Different religions do not need to have the same goals.

Religions are more than worldviews.

6. There is much more to religion than worldviews and beliefs. Religions include community, rituals, images, sounds, hopes, dreams, and stories. Sometimes it is these things -- not the worldviews -- that is most important to people.

We learn by listening.

7. We can bring to interfaith dialogue an appreciation of the role of the arts and music in dialogue, cognizant that, when it comes to knowing the religious other, there are many ways of knowing, including visual and musical and bodily knowing. Prayer and meditation are forms of knowing, too.

We can be transformed by what we hear.

8. One of the aims of dialogue, once trusted relations emerge, is mutual transformation, by which people internalize insights from the other and are transformed in the process.

Our capacities for empathy may be more than we know.

9. Human beings can feel the feelings of other human beings and take on their perspectives, even if they do not have shared histories or common backgrounds.

It's alright to critique one another, too.

10. Once trusted relations emerge, genuine dialogue can include mutual criticism and debate. In genuine dialogue it is alright to say "I disagree." Often we learn more from disagreements than agreements.

Self-critique is extremely important.

11. More important than critiquing others is self-critique. If we absolutize our inherited traditions (ritual and intellectual) and make gods of them, we miss the spirit of creative transformation. We have roots without wings.

We may need to reinvent our religions.

12. Religions are evolving through time, and they are never quire reducible to their inherited patterns and worldviews. Interfaith dialogue and cooperation provide opportunities for the creative development of world religions so they grow less violent, less arrogant, and more hospitable to life.

God is a lure toward dialogue and transformation.

13. The very desire for dialogue and widened horizons comes from a dimension of the universe itself -- a divine yearning -- that is present throughout the world as a spirit of creative transformation.

Interfaith cooperation as practicing the presence of God

14. When we are cooperating with others in respectful ways that help enrich the well-being of life on earth and in local communities, we are practicing the presence of God.

Paul O. Ingram, a theologian and historian of religion, spells out further implications and guidelines in the essay below.