Remembering Appendicitis

Living with Radical Contingency

by Elizabeth Bouvier-Fitzgerald

From the perspective of Open Horizons, living with radical contingency is a spiritual practice. In her essay on appendicitis and in others as well, Elizabeth Bouvier-Fitzgerald reminds us what it it is like to live with radical contingency, amid the multiplicities of life, in a spirit of courage, humor, honesty, and resilience, laced with love. She believes that Jesus, too, lived with such contingency. See her Go Fish: A Life in Christ for the big picture. He, too, knew what it was like to remember appendicitis: that is, the unwanted and confusing sufferings that come our way, which in retrospect can become spiritual teachers, too. (Jay McDaniel)

“I’m here.” – Miss Celie

I wasn’t ready. While I’d eventually inherit my mother’s tendency towards being chronically late, this was not a result of that. We’re never prepared for the moment an organ decides to malfunction. Thankfully life goes on without an appendix. Apparently we’d once used it to digest rubble. Harvest boxes are supposed to more palatable. Some of us disagree. Either way my body had spoken. The nurse in the emergency room turned us away the night before insisting my symptoms were nothing more than cramps delivered straight from hell. The vomiting, paleness and death-wish incited by excruciating pain were part and parcel to a legacy of endometriosis for the women in my family. Incidentally, dear medical profession, figure it out. I hate to think of the number of days lost to confinement on a bathroom floor begging for a miracle, even trying to will my cells into the perfect state of loving health, acceptance or total forgiveness. Mindfulness preachers tell us our bodies are sick because we didn’t forgive hard enough so every month when my uterus knocks me unconscious I Care Bear stare all the cells in my body with love because I refuse to accept Vicodin as the only option for relief. A cure would be preferable to pain killers. Anyway, kale juice and cardio help.

In this case, as with different kinds of pain, dismissable symptoms were masking a very real and treatable problem. The doctor placed two fingers, wide as tongue depressors, above my right hip. Maybe doctors think they’re god because they always have giant hands. What? What? What? My mother’s face in a crisis is always both a yes and a no. She was at once diagnosing, treating and retreating from the situation. My step father was the comic relief. Kiddo, you’re gonna love these drugs. Man I’m jealous. Ho! Ho! Ho! What drugs? They started a pic line so I attempted ejecting myself from the gurney. No one was telling me anything. No one was telling me what was happening or why. And if they were I was so terrified I couldn’t hear them or speak. Two people held down my legs while my parents held my shoulders. Sweetheart, you’re going into surgery. They have to take out your appendix. You’re gonna be fine. Surgery? What? Like now? How much time do I have? I looked at the clock. Later would be good. They have to take you in now.

This was the worst part. There was no time prepare. They pushed something into the line that burned in my vein which only made me scream in protest. Nothing man-made would ever be potent enough to tranquilize the remains of what I’d already lived through. I felt defiantly reassured by their shocked expressions. We can’t give her anymore. I need her out! We have to get in! Consider it done. And that’s when a man almost identical to my recently deceased great grandfather appeared standing over my head with a mask. He’d passed away just nine months before we moved. The carnation I’d taken from the flowers at his funeral had dried but still held its color. Everything around this nice white haired man grew quiet and fuzzy. I could hear what he said. I want you to take a deep breath and count to 3. You’re going to go to sleep and when you wake up your mom and dad will be right here…2, 3.

Only I didn’t go to sleep. While the doctor fished around in the body for the broken part I went off with Edward to explore the hospital. We’d only been living on the island for a month and hadn’t seen much more than our street, the school and South Beach. Warm for October my stepfather kept the side entrance door to the waiting area open with a large rock. It had a yellow smiley face painted on it. I remember laughing and almost disbelieving myself when I saw the painting of who appeared to be Long John Silver mounted above a nautically themed lamp. The lamp featured a ship’s wheel, like something terrible you’d find next to the lobster trap coffee tables at Christmas Tree Shop; a year-round New England mecca where aunties and Nana’s go to buy cheap picture frames, flowery bathroom curtains and shrunken objects that might capture the essence of something much more expensive you saw at Pottery Barn.

My stepfather chain smoked in the courtyard while my mother called her parents from the pay phone describing what was happening to her daughter whose body was covered in a blue paper cloth behind large metal doors. I saw it in the doctor’s hand; a livery looking blot of human tissue. I remember telling my grandpa that just like always I had no face and he told me about all the different items on the shelves above and around the operating table. Like a game of Button Button he asked me to find different things he’d cryptically describe. Then I’d tell him when I’d found the rolls of gauze as wide as tree stumps, the neatly stacked, cake-like boxes of latex gloves, the bottles of iodine that stood shoulder to shoulder like toy soldiers.

Somewhere between our telepathic game and the sound of my mother’s voice a feeling of being submerged under tangible exhaustion extracted me down from the ceiling and back into my body. The next thing to register was the smiling face of a black man who was leaning gently over me, pulling up a blanket. There she is. Where was I? The contrast of noticing my own paralysis and the warm, reassuring strength in this strangers face is as clear now as it was then. Everything about the way he looked at me answered a thousand questions without either of us having to say anything. And then I threw up. According to my mother there was no black male nurse and the anesthesiologist had been a young man with short brown hair.

There are some events in life we can never prepare for. Smart people say get ready for what dreams may come. Others tell us to work harder than we’re already working to strive towards having something more than what we’ve already got. And still others caution against not wanting what isn’t already there. Want this. Don’t want that. Says who? There are many experiences I sometimes wish I could return from wherever they came and still more I’m curious to reach for.

Cautiously curious. I’m afraid if I try for too much either myself or someone I love will die as cosmic punishment for greed. We have a bed, car, jobs and more than one pair of shoes. That’s plenty. I’m also afraid if I stop setting goals that might kill me too. For instance, someday I hope to no longer debrief human suffering. So much is outside our control and yet I haven’t met a person without at least one, maybe secret, hope.

After my great grandfather died we were invited to take something that’d belonged to him. I chose his watch; a silver and elastic hunk of hours. I could smell him in the spaces between the stretchable band. As long as it’s wound and set the face will still tell time. We each pass along various kinds of wealth, culture, stories, traditions, noses; bloodlines that say where we come from which sometimes predict where, how far or simply how we’ll go. Philosophers have tried to tell us the ways free will can be manipulated to multiply or expand time, expunge the ache of living and fill in the gaps with their own definitions of limitlessness. Maybe Kant should’ve gotten appendicitis.

I wasn’t ready. While I’d eventually inherit my mother’s tendency towards being chronically late, this was not a result of that. We’re never prepared for the moment an organ decides to malfunction. Thankfully life goes on without an appendix. Apparently we’d once used it to digest rubble. Harvest boxes are supposed to more palatable. Some of us disagree. Either way my body had spoken. The nurse in the emergency room turned us away the night before insisting my symptoms were nothing more than cramps delivered straight from hell. The vomiting, paleness and death-wish incited by excruciating pain were part and parcel to a legacy of endometriosis for the women in my family. Incidentally, dear medical profession, figure it out. I hate to think of the number of days lost to confinement on a bathroom floor begging for a miracle, even trying to will my cells into the perfect state of loving health, acceptance or total forgiveness. Mindfulness preachers tell us our bodies are sick because we didn’t forgive hard enough so every month when my uterus knocks me unconscious I Care Bear stare all the cells in my body with love because I refuse to accept Vicodin as the only option for relief. A cure would be preferable to pain killers. Anyway, kale juice and cardio help.

In this case, as with different kinds of pain, dismissable symptoms were masking a very real and treatable problem. The doctor placed two fingers, wide as tongue depressors, above my right hip. Maybe doctors think they’re god because they always have giant hands. What? What? What? My mother’s face in a crisis is always both a yes and a no. She was at once diagnosing, treating and retreating from the situation. My step father was the comic relief. Kiddo, you’re gonna love these drugs. Man I’m jealous. Ho! Ho! Ho! What drugs? They started a pic line so I attempted ejecting myself from the gurney. No one was telling me anything. No one was telling me what was happening or why. And if they were I was so terrified I couldn’t hear them or speak. Two people held down my legs while my parents held my shoulders. Sweetheart, you’re going into surgery. They have to take out your appendix. You’re gonna be fine. Surgery? What? Like now? How much time do I have? I looked at the clock. Later would be good. They have to take you in now.

This was the worst part. There was no time prepare. They pushed something into the line that burned in my vein which only made me scream in protest. Nothing man-made would ever be potent enough to tranquilize the remains of what I’d already lived through. I felt defiantly reassured by their shocked expressions. We can’t give her anymore. I need her out! We have to get in! Consider it done. And that’s when a man almost identical to my recently deceased great grandfather appeared standing over my head with a mask. He’d passed away just nine months before we moved. The carnation I’d taken from the flowers at his funeral had dried but still held its color. Everything around this nice white haired man grew quiet and fuzzy. I could hear what he said. I want you to take a deep breath and count to 3. You’re going to go to sleep and when you wake up your mom and dad will be right here…2, 3.

Only I didn’t go to sleep. While the doctor fished around in the body for the broken part I went off with Edward to explore the hospital. We’d only been living on the island for a month and hadn’t seen much more than our street, the school and South Beach. Warm for October my stepfather kept the side entrance door to the waiting area open with a large rock. It had a yellow smiley face painted on it. I remember laughing and almost disbelieving myself when I saw the painting of who appeared to be Long John Silver mounted above a nautically themed lamp. The lamp featured a ship’s wheel, like something terrible you’d find next to the lobster trap coffee tables at Christmas Tree Shop; a year-round New England mecca where aunties and Nana’s go to buy cheap picture frames, flowery bathroom curtains and shrunken objects that might capture the essence of something much more expensive you saw at Pottery Barn.

My stepfather chain smoked in the courtyard while my mother called her parents from the pay phone describing what was happening to her daughter whose body was covered in a blue paper cloth behind large metal doors. I saw it in the doctor’s hand; a livery looking blot of human tissue. I remember telling my grandpa that just like always I had no face and he told me about all the different items on the shelves above and around the operating table. Like a game of Button Button he asked me to find different things he’d cryptically describe. Then I’d tell him when I’d found the rolls of gauze as wide as tree stumps, the neatly stacked, cake-like boxes of latex gloves, the bottles of iodine that stood shoulder to shoulder like toy soldiers.

Somewhere between our telepathic game and the sound of my mother’s voice a feeling of being submerged under tangible exhaustion extracted me down from the ceiling and back into my body. The next thing to register was the smiling face of a black man who was leaning gently over me, pulling up a blanket. There she is. Where was I? The contrast of noticing my own paralysis and the warm, reassuring strength in this strangers face is as clear now as it was then. Everything about the way he looked at me answered a thousand questions without either of us having to say anything. And then I threw up. According to my mother there was no black male nurse and the anesthesiologist had been a young man with short brown hair.

There are some events in life we can never prepare for. Smart people say get ready for what dreams may come. Others tell us to work harder than we’re already working to strive towards having something more than what we’ve already got. And still others caution against not wanting what isn’t already there. Want this. Don’t want that. Says who? There are many experiences I sometimes wish I could return from wherever they came and still more I’m curious to reach for.

Cautiously curious. I’m afraid if I try for too much either myself or someone I love will die as cosmic punishment for greed. We have a bed, car, jobs and more than one pair of shoes. That’s plenty. I’m also afraid if I stop setting goals that might kill me too. For instance, someday I hope to no longer debrief human suffering. So much is outside our control and yet I haven’t met a person without at least one, maybe secret, hope.

After my great grandfather died we were invited to take something that’d belonged to him. I chose his watch; a silver and elastic hunk of hours. I could smell him in the spaces between the stretchable band. As long as it’s wound and set the face will still tell time. We each pass along various kinds of wealth, culture, stories, traditions, noses; bloodlines that say where we come from which sometimes predict where, how far or simply how we’ll go. Philosophers have tried to tell us the ways free will can be manipulated to multiply or expand time, expunge the ache of living and fill in the gaps with their own definitions of limitlessness. Maybe Kant should’ve gotten appendicitis.

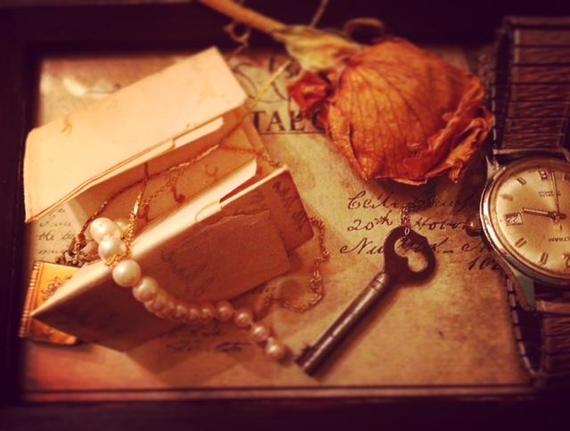

* The photo at the top is a picture of real things I love passed down from people I loved more.

also by the Elizabeth Bouvier-Fitzgerald: