The Center for Process Spirituality in Arkansas

acronym: CaPSA

An introduction by Jay McDaniel and Teri Daily

|

We at CaPSA are about thirty people who form an informal network of spiritually-interested concerned citizens. Many of us are influenced by one of some combination of three sources:

Some of us are businesspersons, some clergy, some artists, some students, some homemakers, some teachers. Some of us are religiously affiliated: Jewish, Christian, Muslim, Buddhist, and Unitarian. And some of us are not; we are secular or "spiritually interested but not religiously affiliated." Some of us are millennials, some generation x-ers, some baby boomers, and some senior citizens. We are interested in an all-age-friendly world that has an interfaith spirit, and that includes being "non-religious" among the faiths.

All of us believe that there is a spiritual side to life that needs to be appreciated and affirmed, publicly as well as privately, by politicians no less than counselors, economists no less than poets. As we see things, spirituality is a combination of emotional intelligence and embodied wisdom: it is wisdom and compassion, kindness and creativity, as embodied in daily life. We have two complementary aims. On the one hand, we want to help people grow in the spiritual side of their lives, so that they can find happiness. We believe that every person has a spiritual inclination in his or her life: a desire to live with creativity, wisdom, curiosity, and compassion each in his or her own way. We want to help people realize this aim. . On the other hand, and importantly. we also believe in social side to spirituality. The need in our time is not simply for whole people, it is also for whole communities and a whole world. We want to help create local communities that are creative, compassionate, participatory, friendly to young and old, multi-religious, culturally diverse, humane to animals, and good for the earth -- with no one left behind. The context for the social side of spirituality is obvious: global climate change, political dysfunction, widening gaps between rich and the rest, the breakdown of local communities, violence and war, degradation of land and landscape, cruelty to animals, widespread depression amid the shallowness of consumer culture. The world does not need to be "perfect," but we do think world can be better, and that many aspects of the world will collapse and result in more tragedy, lest we act now. We work with several institutions with similar aims: The Center for Process Studies (Salem, Oregon), Claremont Institute for Process Studies (Claremont, California), the Institute for Ecological Civilization, the Institute for Postmodern China (China an the US), Pando Populus (Los Angeles), and the Association for Arts, Religion, and Culture. They are our inspiration and partners. In central Arkansas we design and implement four kinds of programs:

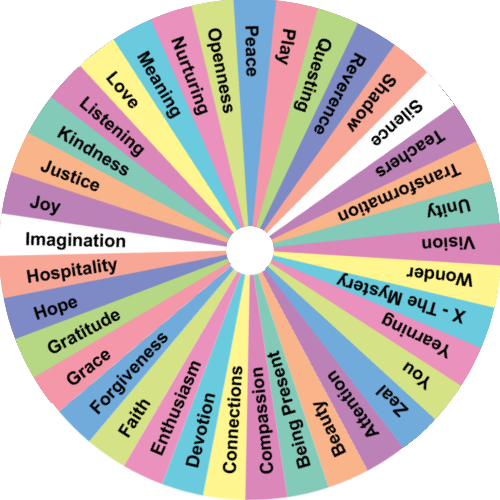

We know that this isn't a lot compared to what others do in larger, urban settings. But it is what we can do, and we hope we make a difference. People often ask us what we mean by "spirituality." The rest of this page is devoted to explaining this. We understand "spirituality" as a combination of emotional intelligence and embodied wisdom that can be understood intuitively and also studied with help from the sciences. We best proceed with the wheel of spirituality, developed by Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat. This wheel helps us appreciate the range of spiritual moods and practices we seek to encourage and help people realize, each in his or her way. |

The Wheel of Interfaith Spirituality

37 Moods and Practices

* We borrow this wheel from the world's leading network of interfaith spiritual understanding:

Spirituality and Practice: https://www.spiritualityandpractice.com/

A Role for Process Philosophy

Many of us at the Center understand the 37 moods and practices with help from a philosophical tradition called process philosophy. In mainland China it is called "constructive postmodernism." Open Horizons offers a growing number of essays helping people interpret some of the moods and practices in a process context. Below you will find some interpretations by Patricia Adams Farmer and Jay McDaniel.

For an introduction to process thinking, see Twenty Key Ideas in Process Thought and also the Whitehead Video Series. For an introduction to process thought in China see Ecological Civilization in China: Our Common Great Opportunity and also Process in China

Spirituality is Daily Life

as lived from the Inside

“Sometimes people get the mistaken notion that spirituality is a separate department of life, the penthouse of our existence. But rightly understood, it is a vital awareness that pervades all realms of our being. Someone will say, “I come alive when I listen to music,” or “I come to life when I garden," or “I come alive when I play golf.” Wherever we come alive, that is the area in which we are spiritual. And then we can say: “I know at least how one is spiritual in that area.” To be vital, awake, aware, in all areas of our lives is the task that is never accomplished, but it remains the goal."

-- David Steindl-Rast, The Music of Silence

Four Contexts

that lead people to care

about the spiritual side of life

We know that the 37 moods and practices identified above are part of the human experience. People do not need to be "religious" in order to experience them. And we know that they emerge naturally in a person's life, whether recognized or not. However we also realize, based on a report on "spirituality" undertaken by the Royal Society for the Arts, a London-based think tank, that four circumstances often give rise to focussed attention on matters of "faith" and "love" and "meaning" and "gratitude" and "hospitality." We call them the Four Contexts.

|

Ten Ideas that Inform our Thinking

- Spirituality is not so much what a person experiences in life as it is how a person responds to what he or she experiences.

- Spirituality lies in being alive, awake, and aware in response to the circumstances of life.

- Spirituality is available to people who are religious, to people who are not, and to the many people who are somewhere in between.

- Spirituality is practical and down to earth, a matter of the hands as well as the heart and mind.

- Spirituality can include and be enriched by belief in a God of boundless love, but it can also include and be enriched by a belief in the horizontal sacred (the sacrality of relationships with people, animals and the earth) even apart from belief in God.

- Spirituality can include and be enriched by participation in a faith community, but can also be separated from such participation.

- Spirituality can help a person negotiate life's circumstances: the longing for love, the desire for connection, the need to be a self, the need to live by faith and hope.

- Spirituality can be studied scientifically as well as introspectively.

- Spirituality can influence and be part of public conversations.

- Spirituality finds its fulfillment, not simply in a sense of individual satisfaction, but in the building and enjoyment of community, both human and ecological.

The RSA Report on Bringing

Spirituality into the Mainstream

A 250 year old think-tank based in London, the RSA, offers an intellectually robust, politically relevant, interdisciplinary understanding of spirituality for the religious and non-religious alike. It is also relevant to the large number of people in the world -- perhaps the majority -- who are in a middle ground between strong belief and strong disbelief.

Building upon research in cognitive psychology, evolutionary biology, culture studies, brain science, mindfulness studies, philosophy, anthropology, and the academic study of religion, the author of the RSA report -- Dr.Jonathon Rowson -- defines spirituality as a form of embodied (viscerally felt) cognition arising out of the depth dimension in life. Spirituality does not begin from the top down but rather, as it were,from the bottom up: that is, from the depths of bodily and cognitive experience.

The cognitive side of spirituality includes self-awareness, emotional intelligence, and sensitivity to the importance of "something more" than the individualized ego. In its mature form it likewise includes kindness, social engagement, and a capacity for being present in the here-and-now. Such spirituality is typically enriched by experiences of aliveness, gratitude, rapture, and homecoming; and it can be cultivated by practices such as meditation, yoga, gardening, running, and prayer.

Four Contexts for Awakening to the Depths

How do people become aware of the depths? Often it is when they become aware of their own need to belong (love), the fact of mortality (death), the mystery of who they truly are (self), or the presence of that cannot be fully contained within objectifying mental grids (soul). Such experiences are the existential springboards for spirituality. But the quality richness of spirituality extends far beyond a consideration of these subjects. Spirituality finds its home in the interstices of everyday life. Indeed it is everyday life, lived from its depths, lovingly.

Understood in this way, spirituality may include but does not necessarily entail, belief in God. God may indeed be the "something more" to which the individual has awakened; but this "something more" may also be the ideals of Truth and Goodness and Beauty, or it may be the natural world, or all of the above, or none of the above. The something more can remain unnamed but nevertheless felt. As felt, the individual feels inclined to live in a less self-centered way, in service to the common good of the world.

Whatever the names, spirituality -- understood as embodied cognition -- is available to theists and non-theists alike, and to the many (perhaps the majority) who are in-between. As Andrew Marr puts it, "many, perhaps most people, live their lives in a tepid confusing middle ground between strong belief and strong disbelief."

Building upon research in cognitive psychology, evolutionary biology, culture studies, brain science, mindfulness studies, philosophy, anthropology, and the academic study of religion, the author of the RSA report -- Dr.Jonathon Rowson -- defines spirituality as a form of embodied (viscerally felt) cognition arising out of the depth dimension in life. Spirituality does not begin from the top down but rather, as it were,from the bottom up: that is, from the depths of bodily and cognitive experience.

The cognitive side of spirituality includes self-awareness, emotional intelligence, and sensitivity to the importance of "something more" than the individualized ego. In its mature form it likewise includes kindness, social engagement, and a capacity for being present in the here-and-now. Such spirituality is typically enriched by experiences of aliveness, gratitude, rapture, and homecoming; and it can be cultivated by practices such as meditation, yoga, gardening, running, and prayer.

Four Contexts for Awakening to the Depths

How do people become aware of the depths? Often it is when they become aware of their own need to belong (love), the fact of mortality (death), the mystery of who they truly are (self), or the presence of that cannot be fully contained within objectifying mental grids (soul). Such experiences are the existential springboards for spirituality. But the quality richness of spirituality extends far beyond a consideration of these subjects. Spirituality finds its home in the interstices of everyday life. Indeed it is everyday life, lived from its depths, lovingly.

Understood in this way, spirituality may include but does not necessarily entail, belief in God. God may indeed be the "something more" to which the individual has awakened; but this "something more" may also be the ideals of Truth and Goodness and Beauty, or it may be the natural world, or all of the above, or none of the above. The something more can remain unnamed but nevertheless felt. As felt, the individual feels inclined to live in a less self-centered way, in service to the common good of the world.

Whatever the names, spirituality -- understood as embodied cognition -- is available to theists and non-theists alike, and to the many (perhaps the majority) who are in-between. As Andrew Marr puts it, "many, perhaps most people, live their lives in a tepid confusing middle ground between strong belief and strong disbelief."

A need for mature spirituality in the public realm"In a culture often thought to be shallow, awash with unfettered consumerism, celebrity gossip, status updates and formulaic scandals, and with our world leaders and politicians seemingly incapable of tackling the major problems of our age, such as climate change, inequality and widespread political alienation, the need and appetite for more ‘depth’ is palpable....To this end, we argue that spirituality should play a greater role in the public realm.' (The RSA) Understood in a way that is intellectually robust and politically relevantThe capacious term ‘spirituality’ lacks clarity because it is not so much a unitary concept as a signpost for a range of touchstones; our search for meaning, our sense of the sacred, the value of compassion, the experience of transcendence, the hunger for transformation...There is little doubt that spirituality can be interesting, but what needs to be made clearer by those who take that for granted is why it is also important. To be a fertile idea for those with terrestrial power or for those who seek it, we need a way of speaking of the spiritual that is intellectually robust and politically relevant.' (The RSA) Understanding ourselves as fundamentally a social species'The notion of a profit-maximising individual who makes decisions consciously, consistently and independently is, at best, a very partial account of who we are. Science is now telling us what most of us intuitively sense: humans are a fundamentally social species. What is the RSA?An emerging view of human natureThe RSA "is a London-based, British organisation committed to finding practical solutions to social challenges. Founded in 1754 as the Society for the encouragement of Arts, Manufacture and Commerce, it was granted a Royal Charter in 1847, and the right to use the term Royal in its name by King Edward VII in 1908. The shorter version, The Royal Society of Arts and the related RSA acronym, are used more frequently than the full name. Charles Dickens, Adam Smith, Benjamin Franklin, Karl Marx, William Hogarth, John Diefenbaker, Stephen Hawking and Tim Berners-Lee are some of the notable past and present members, and today it has Fellows elected from 80 countries worldwide." (from Wikipedia) Many people think of themselves as having a spiritual aspect to their lives, but without really knowing what that means. This report puts forth that whilst spiritual identification is an important part of life for millions of people, it currently remains ignored because it struggles to find coherent expression and, therefore, lacks credibility in the public domain. |

Beyond reference points of atheism and religion"We are examining how new scientific understandings of human nature might help us reconceive the nature and value of spiritual perspectives, practices and experiences. Our aim is to move public discussions on such fundamental matters beyond the common reference points of atheism and religion, and do so in a way that informs non-material aspirations for individuals, communities of interest and practice, and the world at large.'" (The RSA) Developed with help from the neural

|