Process Resource Page

a multi-purpose page to help you learn about and explore

Process Philosophy, Process Theology

and Process Thought

while on your own, in the classroom,

or in an informal group.

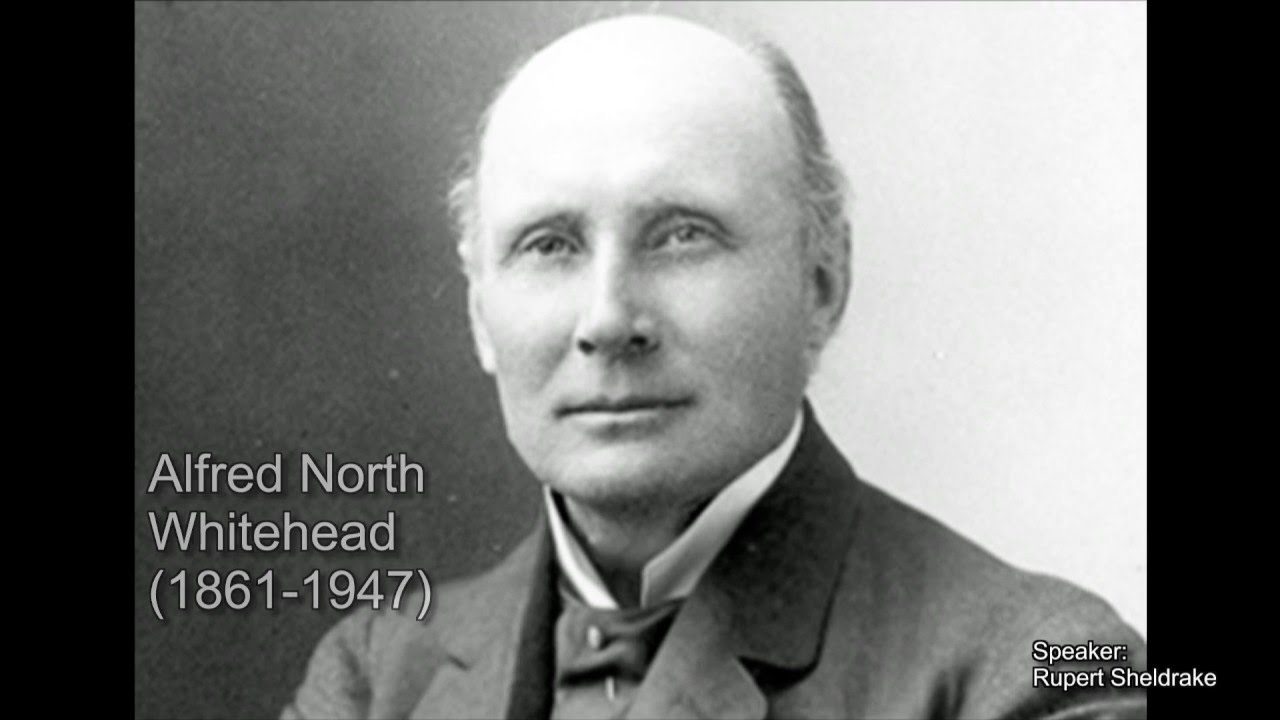

This page is for people in different parts of the world who want to learn about process philosophy, process theology, and process thought -- and also for curious readers who want to dig into Whitehead's Process and Reality. Scroll down for videos that will help you read Whitehead's book, and scroll a little further for thumbnail sketches of each video. If you are more interested in the general ideas than in the philosophy of Whitehead, and in the applications of these ideas to multiple subjects click on the links to find short articles on a variety of subjects in the process tradition: ranging from Process and Buddhism through Process and Music to "Process and Ecological Civilization.

|

About the Videos Below

Below please find twenty videos plus an introductory video that will help you or others get started in understanding the philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead. Each video lasts about six minutes. I developed the series to help friends in mainland China read Process and Reality in the absence of a teacher, but have since discovered that the series is useful in other parts of the world as a guide in reading Process and Reality. The video series can stand on its own as a companion to reading Process and Reality, but in the college classroom I use it in combination with two other secondary sources: John Cobb’s Whitehead Word Book and Robert Mesle’s Process-Relational Philosophy. In my experience the video series, plus these two texts, can help people negotiate Process and Reality in a satisfying and exciting way. The video series is intended to accompany a slow and careful reading of Process and Reality, but you can also “skip around” if you wish. Here are some suggestions:

Finally I must note that my interpretation of Process and Reality is decidedly phenomenological -- that is, focused on the relevance of Whitehead's philosophy to human experience -- as opposed to, say, a more scientific way of reading that focuses on an objective world independent of its relevance to, and resonance with, daily life. I think both approaches are valuable; and that both informed Whitehead as he wrote Process and Reality. He was interested in actual entities as drops of human experience in daily life, and actual entities at energy-events in the depths of atoms. I focus on human experience but am grateful to those who take heed of the atoms. What makes Whitehead so interesting is that he was interested in both worlds: the human and the more-than-human. He appeals to scientists and poets at the same time. He was, I believe, a philosopher for our time. -- Jay McDaniel (1/12/2018) |

Special Topics:

|

Reading Whitehead's Process and Reality

Reading Whitehead's Magnum Opus on your own

with help from a video series, scroll down

for synopsis of each video

Thumbnail Sketch of the Videos

Introduction

Process Thought is an Attitude and Outlook on Life,

International in Scope, Influenced by the Philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead

This video introduces process thought and explains the purpose of the series. Dr. Jay McDaniel (the narrator) introduces himself and presents process thought as an attitude toward life emphasizing creativity, interconnectedness, and respect for life. He gives you a sense of who and where process thinkers are, and he introduces a diagram -- the Tree Diagram -- which compares process thought to a growing tree.

The roots are Whitehead's philosophy; the trunk consists of twenty key ideas that flow from his philosophy; and the brances consist of application. The twenty key ideas can be found in English and Chinese on the JJB website: Twenty Key Ideas. JJB also introduces many applications of process thinking on a wide variety of topics: ecology, education, culture, spirituality, science, art, music, and food culture, for example.

For example, if you are interested in practical applications to ecology, see John Cobb's Ten Ideas for Saving the Planet. Or if you are interested in spirituality, see Replanting Yourself in Beauty or Trust in Beauty.

However, this course focuses on the roots as developed in Whitehead's Process and Reality. As you take the course it is helpful, but not necessary, to have a copy of Whitehead's Process and Reality alongside you, making sure that you read the selected pages. It is best to read the text very slowly, without rushing. Do not worry if there are phrases you do not understand. If you watch and reflect upon these videos, you will have a good understanding of many ideas in Process and Reality.

Lesson One

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, Preface, pages xi-xii

Key Theme: There are four sources for wisdom: Science, Art, Religion, and Ethics.

This lesson focuses on the first two pages of the preface to Process and Reality. With help from highlighted texts, it presents Whitehead's aims in writing the book; explains that Whitehead spoke of his philosophy as a philosophy of organism; and talks about four kinds of experience Whitehead wanted to unify: scientific, aesthetic, moral, and religious. At the end Dr. McDaniel explains that, for Whitehead, the wisdom of the perspective he develops will lie in the overall scheme, and that this scheme is gradually developed throughout the book.

Lesson Two

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, Preface, page xiii

Key Theme: Thinking and feeling and decision-making form a whole.

Following a brief review of the previous lesson, this lesson turns to a list of nine fallacies which Whitehead lists in the preface found on page xiii of the Preface. These are fallacies which Whitehead seeks to avoid. This lesson focuses on three of them: (1) the fallacy of distrusting speculative philosophy, (2) the fallacy of trusting that language is an adequate expression of ideas, and (3) the fallacy of thinking that the human mind can be divided into mutually external compartments or faculties.

Lesson Three

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, Preface, page xiii (cont.)

Key Theme: Reality does not conform to subject-predicate grammar.

Lesson three continues in explication of nine ideas repudiated or rejected by Whitehead as he begins to develop his philosophy. After a short review of the previous lesson, Dr. McDaniel discusses one of the most important "fallacies" Whitehead sought to avoid. It is that of thinking that the world in which we live, and our experience of it, can be understood on the analogy of the subject-predicate mode of grammatical expression. In so doing the lesson introduces an idea that is central to the process tradition: namely that "entities" emerge out of their relations with other "entities" and that there are no entities existing in isolation. The emphasis on relationality is one reason that Whitehead called his philosophy a philosophy of organism.

Lesson Four

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, Preface, page xiii (cont.)

Key Theme: In philosophy no form of experience should be excluded.

Lesson Four presents Whitehead's idea that the starting point for philosophical thought is experience and explains that, for Whitehead, all kinds of experience must be taken into account: experience anxious and carefree, experience happy and grieving, experience emotional and experience intellectual, experience normal and abnormal, experience asleep and experience awake. This lesson also introduces the idea that Whitehead was a radical empiricist, rejecting the sensationalist doctrine of perception in the interests of recognizing the potential wisdom of many forms of experience.

Lesson Five

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, Preface, page xiii (cont.)

Key Theme: There are no vacuous actualities; nature is alive.

With help from visual images from the French artist and post-Impressionist painter, Paul Cezanne (1839-1906), this lesson introduces Whitehead's idea that the whole of the universe is "alive" in varying degrees and ways, and that there are no vacuous actualities. A vacuous actuality is an actuality which lacks any interiority or agency; it is a mere thing. Whitehead's philosophy is known for its proposal that all genuine actualities in our universe prehend their actual worlds from their own perspective, and that the objects we see in our world are either genuine actualities in their own right or nexus (aggregates) of such actualities. Mountains, for example, are aggregate expressions of actualities with prehensive vitality. One well-known process philosopher, David Ray Griffin, speaks of this as panexperientialism. In this website we sometimes call it panprehensionality. Whitehead's notion of prehension is dealt with in a subsequent lesson.

Lesson Six

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, Preface, page xiv

Key Theme: We all have worldviews, but no one has the final word.

Lesson Six introduces four impressions that dominate Whitehead's thinking as he writes Process and Reality: (1) The age of criticism has done it's work, and it is time for construction, (2) the true method of philosophical construction is to frame a set of ideas, drawing from many forms of experience, and see if they help interpret and illuminate experience, (3) all forms of thought are influenced by a philosophical scheme of one sort or another, acknowledged or not, and (4) when it comes to sounding the depths of things, all schemes are finite and fallible. "The merest hint of dogmatic certainty as to finality of statement is an exhibition of folly."

Lesson Seven

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, page 7

Key Theme: Creativity is the ultimate reality of the universe

Lesson Seven explores four key themes, based on a very important paragraph in the first chapter of Part One of Process and Reality. The ideas are that (1) the ultimate reality is Creativity, which is ultimate by virtue of its actualizations; (2) God is the primordial self-actualization of creativity, but not the ultimate reality itself, (3) the emphasis on Creativity resembles Asian -- Chinese and Indian -- ways of thinking; and (4) when it comes to thinking about ultimates, some process thinkers (but not Whitehead himself) speak of different kinds of ultimates around which different cultural and religious traditions may be centered.

Lesson Eight

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, page 22

Key Idea: The actual entity is a process of prehending the actual world.

Lesson Eight begins the process of explicating the eight key "categories of existence" as adumbrated in Whitehead's Process and Reality. Among Whiteheadians there are two complementary ways of understanding an actual entity. One way begins with submicroscopic matter and works "up" to human experience. It presents actual entities as very tiny energy-events with the depths of matter. The other way begins with a single moment of human experience and works "down" to submicroscopic matter. It presents actual entities as activities, or processes, amid which, in the moment at hand, a human being feels the presence of the actual world. This lesson begins in the second way. It embodies what philosophers might call a phenomenological approach to Whitehead's idea of an actual entity. In the tradition of Whiteheadian scholarship there are many approaches: phenomenological, speculative, and post-structural.

Phenomenological approaches begin with lived human experience; speculative approaches begin with speculations about the universe; post-structural approaches begin more general sensibilities concerning multiplicity, difference, interconnectedness, and flow. In these lessons we often begin phenomenologically, but feel free to turn in the other two directions. And so it is with most Whiteheadian thinkers.

Lesson Nine

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, page 21

Key Idea: The many become one and are increased by one.

Lesson Nine considers selected passages from six paragraphs in a section of Whitehead's Process and Reality called The Category of the Ultimate. One of the most important ideas presented in these passages is that Creativity is, in Whitehead's words, "the universal of universals characterizing ultimate matters of fact." His idea is that every actual fact in the universe -- every actual entity -- is a "production of novel togetherness." This means that an entity is not simply "one" but also "many." It is the many becoming one. The video uses the example of a child's relationship to her parents to illustrate the point. Her parents are part of who she is, and in her very inclusion of them within her own life, she is more than them. Always she is becoming herself, and the self who becomes at any given moment becomes part of a many which influence her in the future.

Lesson Ten

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, page 18

Key Theme: Everything - even God -- is an act of experiencing.

Lesson Ten focuses on a unique paragraph in Process and Reality, where Whitehead proposes an answer to the question: What is everything made of? Whereas some traditions in the world might way that everything is made of something like matter and whereas some might say that everything is made of consciousness; Whitehead proposes a more Buddhist or Chinese response. Everything is made of events or, to be more specific, drops of experience, complex and interdependent. Here we find a vivid instance of Whitehead's event-cosmology. In traditional Chinese thinking philosophers speak of the totality of all that exists as wan wu (萬物) sometimes translated as the Ten Thousand Things. In a Whiteheadian context the Ten Thousand Things are Ten Thousand Events. There is nothing more real than events, and they are themselves drops of experience. At any given moment we ourselves are events composed of our own experience, yet related to everything else in the universe. God is an event, too. And so is a puff of energy in outer space. The universe is a vast unfolding network of inter-being or, perhaps better, inter-events.

Lesson Eleven

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, page 39

Key Idea: There are two kinds of reality: actuality and potentiality.

In Whitehead's philosophy something is "real" if it can be experienced as an object of one sort or another and thus, as an object, make a difference in experience. Lesson Eleven introduces the idea that some objects of experience are possibilities rather than actualities. They are real but not actual, because they do not feel or prehend their surroundings and do not make decisions. The most abstract of these objects are what Whitehead calls eternal objects. They are pure potentials which may be actualized in some universe or cosmic epoch, even if not our own. These objects are similar to Plato's Forms, and Whitehead was indeed influenced by Plato. The lesson concludes with remarks concerning the creative and performing arts and the natural sciences, suggesting that they are ways of exploring and presenting potentialities.

Lesson Twelve

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, page 23

Key Idea: Propositions are not simply statements of belief; they are lures for feeling.

Lesson Twelve discusses Whitehead's idea of a proposition -- or lure for feeling -- showing how propositions are means by which novelty enters the world. By way of illustration, this segment plays some of the music of the jazz musician, John Coltrane, and presents propositions in light of the innovative spirit of jazz. Whitehead proposes that, at every moment of our lives, we are improvising responses to given situations, adding our own voice to the very history of the universe. Other creatures are doing this, too. We live in an improvisational universe, in which indeterminacy is as real, and as important, as determinacy. Thus, for Whitehead, the future is always open, and the future is never entirely pre-determined by the past or the present. This is the case even for God, who knows what is possible in the future, but not what is actual until it becomes actual.

Lesson Thirteen

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, page 51.

Key Idea: Prehensions are the means by which entities are present in others.

Lesson Thirteen introduces two of the most important ideas in Whitehead's philosophy: prehensions and subjective forms. . Every actual entity, every moment of experience, consists of acts of experiencing or prehending many realities which "become one" in the act of experiencing them. The realities can be other actual entities or pure potentialities, or combinations of them. Prehensions may be conscious or unconscious; in human life most are unconscious. Consciousness is but the tip of the experiential iceberg. Prehensions are the most fundamental element in actual entities, the means by which the universe is held together and things are present in one another. Lesson Thirteen takes a conversation between a mother and her daughter as a way of illustration prehension and their complementary notion: subjective forms.

Lesson Fourteen

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, page 34.

Key Idea: Reality is thoroughly social. Molecules and atoms, planets and stars are societies, too. There are no self-contained facts.

Lesson Fourteen introduces the ideas of nexus and society to readers. Most of the macroscopic objects that we perceive around us are not single actual entities, but rather aggregates of actual entities unified by their prehensions of one another (nexus) and perhaps also by a common characteristic which they inherit from predecessors in the the nexus, thus giving them more specific definition (society). There are many kinds of societies. A human being is a society too. She is a personally-ordered society who consists of many moments of experience (many actual entities) in succession, each inheriting from the predecessors with special intimacy. There is no single person who underlies the change; there are many subjects in succession. The idea is very Buddhist: "No thinker thinks twice and no experiencer experiences twice." Lesson Fourteen ends by offering the idea that perhaps the universe as a whole is gathered into an ongoing Life, too. This is what Whitehead means by the consequent nature of God.

Lesson Fifteen

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, page 81.

Key Idea: The body plays an essential role in human life: the withness of the body.

Lesson Fifteen introduces three ideas that are important to Whitehead in Process and Reality: the withness of the body, experience in the mode of causal efficacy, and experience in the mode of presentational immediacy. Experience in the mode of causal efficacy is visceral experience. It occurs when we feel affected or influenced by bodily states and by realities outside our bodies in direct, energetic ways. It is an important part of bodily experience and serves a perpetual reminder that, in our daily lives, we are with our bodies and our bodies are with us. Whitehead calls it the withness of the body. This does not mean that our minds are precisely identifical with our bodies; we can have attitudes toward our bodies which are healthy or unhealthy, and these attitudes occur in our minds. But our bodies are marvelously intricate and complex systems of energy which nourish us, give us a sense of direction, offer us wisdom, and connect us with the world. And ultimately, says Whitehead, the whole world is like a body to us. Even God -- if God exists-- is embodied. The universe is God's body.

Lesson Sixteen

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, page 43

Key Idea: Decision is the very meaning of actuality

Lesson Sixteen focuses on Whitehead's idea that the very meaning of actuality lies in the notion of decision. In Whitehead's philosophy a decision is not a "conscious" decision, but rather a subjectivity activity -- conscious or unconscious -- in which some possibilities for responding to a given situation are excluded or cut off, while others are then actualizes. A woman climbing a mountain, movement by moment, is making conscious decisions which constitute her very actualityi in the moment at hand. And so, thinks Whitehead, are the energy-events within the very depths of atoms. Understood in this way, decision is one of the primary expressions of the ultimate reality of the universe: creativity. Decisions may be wise or unwise, productive or destructive, violent or graceful -- whatever their nature, they are the very reason why things unfolds as they do. From Whitehead's perspective the universe is not simply an unfolding of abstract ideas. The world is not the outcome of mathematical formulas. It is the outcome of decisions.

Lesson Seventeen

Key Text: Process and Reality, pages 48-51.

Key Idea: Every moment of human experience is a concrescence of the universe.

Lesson Seventeen offers the most systematic summary of Whitehead's idea of experience available in this series of videos. The diagrams were created by a student at Hendrix College in Conway, Arkansas, USA. There is a danger in diagrams, insofar as they can lead people into overly-static and linear ways of looking at the world. Whitehead's philosophy is more holistic and dynamic. This means that, when we think of experience, we need to hold onto diagrams with a relaxed grasp, fully aware that experience is always more than images. Nevertheless, the diagrams may help viewers more fully understand Whitehead's concept of experience. In the narrative the experiencing subject is imagined as a human being, but it is important to remember that, in Whitehead's philosophy, there is subjectivity everywhere: in the infinitely small and the infinitely large. Even in the depths of atoms, and even in the depths of God, there is something akin to what is depicted in the diagrams: prehending, subjective form, and decision. However, in God, as Whitehead understands God, there is no perishing of immediacy. God is the inclusive and everlasting act of concrescence who shares in all finite moments such as those depicted above. (See Lesson Nineteen.)

Lesson Eighteen

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, page 229

Key Idea: The beauty of life is felt in contrast; the aim of life is to weave them.

Lesson Eighteen introduces an idea which is extremely important to Whitehead, and which he lists as among the eight categories of existence he seeks to illuminate in Process and Reality. This is the idea of contrasts. For some in the English-speaking world, the word contrast can suggest conflict; but for Whitehead it suggested complementarity. The yin-yang diagram in traditional Chinese thinking offers a helpful image of contrasts. Whitehead was interested in how we can experience objects in the world through contrasts, and also in how we try to weave our own emotions -- our subjective forms -- into contrasts. He believed that all experiencing subjects, anywhere in the universe, are seeking contrasts or, to use another word important to him, beauty. They - we -- seek harmony and intensity, neither to the exclusion of the other. In the very seeking there is a zest or vitality which, for Whitehead, is part of life's meaning. Even the adventure of the universe as One -- even God -- is enriched by and forever seeking a harmony of contrasts.

Lesson Nineteen

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, pages 342-351

Relevant Idea: God is a non-coercive guide and a fellow sufferer who understands.

Lesson Nineteen presents Whitehead's understanding of God. This is an aspect of Whitehead's cosmology which which many religiously-minded people find especially important: whether Jewish or Muslim or Christian, Hindu or Taoist or Buddhist. In Whitehead's philosophy God has two aspects: a non-coercive but guiding aspect which is home to all the potentialities which the universe can actualize, and which is within each experiencing subject as its own innermost lure toward full aliveness; and a receptive side which shares in the experiences of all living beings, anywhere and everywhere, and is affected by all that is felt. God is, as it were, the deep Mind and the deep Listening. Whitehead thought it more rational to believe in God, thus understood, than not to believe in God; and he believed that this way of thinking about God is consonant with the view of the universe we gain from post-mechanistic science. In a later book, Adventures of Ideas, he speaks of the guiding side of God as an Eros by which the universe is lured into adventure, moment by moment, epoch by epoch; and the receptive side as a Harmony of Harmonies within which, in certain moments, the restlessness of adventure drops away and people feel deep peace.

Lesson Twenty

Relevant Text: Process and Reality as a Whole

Key Idea: Why Whitehead? So many reasons.

Lesson Twenty brings the series to a close by articulating various reasons why people in different parts of the world are attracted to Whitehead's philosophy. To the many reasons identified in the video, one very important reason should be added. Many scholars in the academic world believe that Whitehead's philosophy can advance knowledge in specific disciplines: chemistry, physics, psychology, sociology, biology, philosophy, economics, business, culture studies. The work of the Center for Process Studies in Claremont, California, can introduce readers to developments in these and many other areas. It is the best single, online resource for finding resources and keeping abreast of developments within the disciplines.

At the same time, Whitehead's philosophy offers a way of moving beyond the disciplinary fragmentation that has separated academic disciplines from one another and from forms of practice, in real world, which might help guide the world toward sustainable communities. When it comes to practicing process thought, some Whiteheadian thinkers turn toward particular questions of public policy: economics,agriculture, manufacturing, education, governance. In this website, John Cobb's Ten Ideas for Saving the Planet and Foundations for a New Civilization offers an intimation of the policy-oriented directions. There is also much work being done today using Whitehead's thought encourage cross-cultural dialogue, including inter-religious dialogue. Why Whitehead? So many reasons.

This does not mean that Whitehead's philosophy has all the answers. For Whiteheadians the world needs many points of view, including many which offer critiques of Whitehead's own thinking. Whitehead hoped that his own ideas would be tested, applied, revised and, where necessary, replaced. And he did not want his philosophy to be turned into a dogma. Recall the point he makes in the preface: "How shallow, puny, and imperfect are efforts to sound the depths in the nature of things. In philosophical discussion, the merest hint of dogmatic certainty as to finality of statement is an exhibition of folly." (xiv) Process philosophy is more -- much more -- than Whitehead. It is an ongoing tradition, inspired by Whitehead's ideas, but moving beyond his thinking, too, fully cognizant that there are no final answers, only lures for feeling.

Process Thought is an Attitude and Outlook on Life,

International in Scope, Influenced by the Philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead

This video introduces process thought and explains the purpose of the series. Dr. Jay McDaniel (the narrator) introduces himself and presents process thought as an attitude toward life emphasizing creativity, interconnectedness, and respect for life. He gives you a sense of who and where process thinkers are, and he introduces a diagram -- the Tree Diagram -- which compares process thought to a growing tree.

The roots are Whitehead's philosophy; the trunk consists of twenty key ideas that flow from his philosophy; and the brances consist of application. The twenty key ideas can be found in English and Chinese on the JJB website: Twenty Key Ideas. JJB also introduces many applications of process thinking on a wide variety of topics: ecology, education, culture, spirituality, science, art, music, and food culture, for example.

For example, if you are interested in practical applications to ecology, see John Cobb's Ten Ideas for Saving the Planet. Or if you are interested in spirituality, see Replanting Yourself in Beauty or Trust in Beauty.

However, this course focuses on the roots as developed in Whitehead's Process and Reality. As you take the course it is helpful, but not necessary, to have a copy of Whitehead's Process and Reality alongside you, making sure that you read the selected pages. It is best to read the text very slowly, without rushing. Do not worry if there are phrases you do not understand. If you watch and reflect upon these videos, you will have a good understanding of many ideas in Process and Reality.

Lesson One

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, Preface, pages xi-xii

Key Theme: There are four sources for wisdom: Science, Art, Religion, and Ethics.

This lesson focuses on the first two pages of the preface to Process and Reality. With help from highlighted texts, it presents Whitehead's aims in writing the book; explains that Whitehead spoke of his philosophy as a philosophy of organism; and talks about four kinds of experience Whitehead wanted to unify: scientific, aesthetic, moral, and religious. At the end Dr. McDaniel explains that, for Whitehead, the wisdom of the perspective he develops will lie in the overall scheme, and that this scheme is gradually developed throughout the book.

Lesson Two

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, Preface, page xiii

Key Theme: Thinking and feeling and decision-making form a whole.

Following a brief review of the previous lesson, this lesson turns to a list of nine fallacies which Whitehead lists in the preface found on page xiii of the Preface. These are fallacies which Whitehead seeks to avoid. This lesson focuses on three of them: (1) the fallacy of distrusting speculative philosophy, (2) the fallacy of trusting that language is an adequate expression of ideas, and (3) the fallacy of thinking that the human mind can be divided into mutually external compartments or faculties.

Lesson Three

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, Preface, page xiii (cont.)

Key Theme: Reality does not conform to subject-predicate grammar.

Lesson three continues in explication of nine ideas repudiated or rejected by Whitehead as he begins to develop his philosophy. After a short review of the previous lesson, Dr. McDaniel discusses one of the most important "fallacies" Whitehead sought to avoid. It is that of thinking that the world in which we live, and our experience of it, can be understood on the analogy of the subject-predicate mode of grammatical expression. In so doing the lesson introduces an idea that is central to the process tradition: namely that "entities" emerge out of their relations with other "entities" and that there are no entities existing in isolation. The emphasis on relationality is one reason that Whitehead called his philosophy a philosophy of organism.

Lesson Four

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, Preface, page xiii (cont.)

Key Theme: In philosophy no form of experience should be excluded.

Lesson Four presents Whitehead's idea that the starting point for philosophical thought is experience and explains that, for Whitehead, all kinds of experience must be taken into account: experience anxious and carefree, experience happy and grieving, experience emotional and experience intellectual, experience normal and abnormal, experience asleep and experience awake. This lesson also introduces the idea that Whitehead was a radical empiricist, rejecting the sensationalist doctrine of perception in the interests of recognizing the potential wisdom of many forms of experience.

Lesson Five

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, Preface, page xiii (cont.)

Key Theme: There are no vacuous actualities; nature is alive.

With help from visual images from the French artist and post-Impressionist painter, Paul Cezanne (1839-1906), this lesson introduces Whitehead's idea that the whole of the universe is "alive" in varying degrees and ways, and that there are no vacuous actualities. A vacuous actuality is an actuality which lacks any interiority or agency; it is a mere thing. Whitehead's philosophy is known for its proposal that all genuine actualities in our universe prehend their actual worlds from their own perspective, and that the objects we see in our world are either genuine actualities in their own right or nexus (aggregates) of such actualities. Mountains, for example, are aggregate expressions of actualities with prehensive vitality. One well-known process philosopher, David Ray Griffin, speaks of this as panexperientialism. In this website we sometimes call it panprehensionality. Whitehead's notion of prehension is dealt with in a subsequent lesson.

Lesson Six

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, Preface, page xiv

Key Theme: We all have worldviews, but no one has the final word.

Lesson Six introduces four impressions that dominate Whitehead's thinking as he writes Process and Reality: (1) The age of criticism has done it's work, and it is time for construction, (2) the true method of philosophical construction is to frame a set of ideas, drawing from many forms of experience, and see if they help interpret and illuminate experience, (3) all forms of thought are influenced by a philosophical scheme of one sort or another, acknowledged or not, and (4) when it comes to sounding the depths of things, all schemes are finite and fallible. "The merest hint of dogmatic certainty as to finality of statement is an exhibition of folly."

Lesson Seven

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, page 7

Key Theme: Creativity is the ultimate reality of the universe

Lesson Seven explores four key themes, based on a very important paragraph in the first chapter of Part One of Process and Reality. The ideas are that (1) the ultimate reality is Creativity, which is ultimate by virtue of its actualizations; (2) God is the primordial self-actualization of creativity, but not the ultimate reality itself, (3) the emphasis on Creativity resembles Asian -- Chinese and Indian -- ways of thinking; and (4) when it comes to thinking about ultimates, some process thinkers (but not Whitehead himself) speak of different kinds of ultimates around which different cultural and religious traditions may be centered.

Lesson Eight

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, page 22

Key Idea: The actual entity is a process of prehending the actual world.

Lesson Eight begins the process of explicating the eight key "categories of existence" as adumbrated in Whitehead's Process and Reality. Among Whiteheadians there are two complementary ways of understanding an actual entity. One way begins with submicroscopic matter and works "up" to human experience. It presents actual entities as very tiny energy-events with the depths of matter. The other way begins with a single moment of human experience and works "down" to submicroscopic matter. It presents actual entities as activities, or processes, amid which, in the moment at hand, a human being feels the presence of the actual world. This lesson begins in the second way. It embodies what philosophers might call a phenomenological approach to Whitehead's idea of an actual entity. In the tradition of Whiteheadian scholarship there are many approaches: phenomenological, speculative, and post-structural.

Phenomenological approaches begin with lived human experience; speculative approaches begin with speculations about the universe; post-structural approaches begin more general sensibilities concerning multiplicity, difference, interconnectedness, and flow. In these lessons we often begin phenomenologically, but feel free to turn in the other two directions. And so it is with most Whiteheadian thinkers.

Lesson Nine

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, page 21

Key Idea: The many become one and are increased by one.

Lesson Nine considers selected passages from six paragraphs in a section of Whitehead's Process and Reality called The Category of the Ultimate. One of the most important ideas presented in these passages is that Creativity is, in Whitehead's words, "the universal of universals characterizing ultimate matters of fact." His idea is that every actual fact in the universe -- every actual entity -- is a "production of novel togetherness." This means that an entity is not simply "one" but also "many." It is the many becoming one. The video uses the example of a child's relationship to her parents to illustrate the point. Her parents are part of who she is, and in her very inclusion of them within her own life, she is more than them. Always she is becoming herself, and the self who becomes at any given moment becomes part of a many which influence her in the future.

Lesson Ten

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, page 18

Key Theme: Everything - even God -- is an act of experiencing.

Lesson Ten focuses on a unique paragraph in Process and Reality, where Whitehead proposes an answer to the question: What is everything made of? Whereas some traditions in the world might way that everything is made of something like matter and whereas some might say that everything is made of consciousness; Whitehead proposes a more Buddhist or Chinese response. Everything is made of events or, to be more specific, drops of experience, complex and interdependent. Here we find a vivid instance of Whitehead's event-cosmology. In traditional Chinese thinking philosophers speak of the totality of all that exists as wan wu (萬物) sometimes translated as the Ten Thousand Things. In a Whiteheadian context the Ten Thousand Things are Ten Thousand Events. There is nothing more real than events, and they are themselves drops of experience. At any given moment we ourselves are events composed of our own experience, yet related to everything else in the universe. God is an event, too. And so is a puff of energy in outer space. The universe is a vast unfolding network of inter-being or, perhaps better, inter-events.

Lesson Eleven

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, page 39

Key Idea: There are two kinds of reality: actuality and potentiality.

In Whitehead's philosophy something is "real" if it can be experienced as an object of one sort or another and thus, as an object, make a difference in experience. Lesson Eleven introduces the idea that some objects of experience are possibilities rather than actualities. They are real but not actual, because they do not feel or prehend their surroundings and do not make decisions. The most abstract of these objects are what Whitehead calls eternal objects. They are pure potentials which may be actualized in some universe or cosmic epoch, even if not our own. These objects are similar to Plato's Forms, and Whitehead was indeed influenced by Plato. The lesson concludes with remarks concerning the creative and performing arts and the natural sciences, suggesting that they are ways of exploring and presenting potentialities.

Lesson Twelve

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, page 23

Key Idea: Propositions are not simply statements of belief; they are lures for feeling.

Lesson Twelve discusses Whitehead's idea of a proposition -- or lure for feeling -- showing how propositions are means by which novelty enters the world. By way of illustration, this segment plays some of the music of the jazz musician, John Coltrane, and presents propositions in light of the innovative spirit of jazz. Whitehead proposes that, at every moment of our lives, we are improvising responses to given situations, adding our own voice to the very history of the universe. Other creatures are doing this, too. We live in an improvisational universe, in which indeterminacy is as real, and as important, as determinacy. Thus, for Whitehead, the future is always open, and the future is never entirely pre-determined by the past or the present. This is the case even for God, who knows what is possible in the future, but not what is actual until it becomes actual.

Lesson Thirteen

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, page 51.

Key Idea: Prehensions are the means by which entities are present in others.

Lesson Thirteen introduces two of the most important ideas in Whitehead's philosophy: prehensions and subjective forms. . Every actual entity, every moment of experience, consists of acts of experiencing or prehending many realities which "become one" in the act of experiencing them. The realities can be other actual entities or pure potentialities, or combinations of them. Prehensions may be conscious or unconscious; in human life most are unconscious. Consciousness is but the tip of the experiential iceberg. Prehensions are the most fundamental element in actual entities, the means by which the universe is held together and things are present in one another. Lesson Thirteen takes a conversation between a mother and her daughter as a way of illustration prehension and their complementary notion: subjective forms.

Lesson Fourteen

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, page 34.

Key Idea: Reality is thoroughly social. Molecules and atoms, planets and stars are societies, too. There are no self-contained facts.

Lesson Fourteen introduces the ideas of nexus and society to readers. Most of the macroscopic objects that we perceive around us are not single actual entities, but rather aggregates of actual entities unified by their prehensions of one another (nexus) and perhaps also by a common characteristic which they inherit from predecessors in the the nexus, thus giving them more specific definition (society). There are many kinds of societies. A human being is a society too. She is a personally-ordered society who consists of many moments of experience (many actual entities) in succession, each inheriting from the predecessors with special intimacy. There is no single person who underlies the change; there are many subjects in succession. The idea is very Buddhist: "No thinker thinks twice and no experiencer experiences twice." Lesson Fourteen ends by offering the idea that perhaps the universe as a whole is gathered into an ongoing Life, too. This is what Whitehead means by the consequent nature of God.

Lesson Fifteen

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, page 81.

Key Idea: The body plays an essential role in human life: the withness of the body.

Lesson Fifteen introduces three ideas that are important to Whitehead in Process and Reality: the withness of the body, experience in the mode of causal efficacy, and experience in the mode of presentational immediacy. Experience in the mode of causal efficacy is visceral experience. It occurs when we feel affected or influenced by bodily states and by realities outside our bodies in direct, energetic ways. It is an important part of bodily experience and serves a perpetual reminder that, in our daily lives, we are with our bodies and our bodies are with us. Whitehead calls it the withness of the body. This does not mean that our minds are precisely identifical with our bodies; we can have attitudes toward our bodies which are healthy or unhealthy, and these attitudes occur in our minds. But our bodies are marvelously intricate and complex systems of energy which nourish us, give us a sense of direction, offer us wisdom, and connect us with the world. And ultimately, says Whitehead, the whole world is like a body to us. Even God -- if God exists-- is embodied. The universe is God's body.

Lesson Sixteen

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, page 43

Key Idea: Decision is the very meaning of actuality

Lesson Sixteen focuses on Whitehead's idea that the very meaning of actuality lies in the notion of decision. In Whitehead's philosophy a decision is not a "conscious" decision, but rather a subjectivity activity -- conscious or unconscious -- in which some possibilities for responding to a given situation are excluded or cut off, while others are then actualizes. A woman climbing a mountain, movement by moment, is making conscious decisions which constitute her very actualityi in the moment at hand. And so, thinks Whitehead, are the energy-events within the very depths of atoms. Understood in this way, decision is one of the primary expressions of the ultimate reality of the universe: creativity. Decisions may be wise or unwise, productive or destructive, violent or graceful -- whatever their nature, they are the very reason why things unfolds as they do. From Whitehead's perspective the universe is not simply an unfolding of abstract ideas. The world is not the outcome of mathematical formulas. It is the outcome of decisions.

Lesson Seventeen

Key Text: Process and Reality, pages 48-51.

Key Idea: Every moment of human experience is a concrescence of the universe.

Lesson Seventeen offers the most systematic summary of Whitehead's idea of experience available in this series of videos. The diagrams were created by a student at Hendrix College in Conway, Arkansas, USA. There is a danger in diagrams, insofar as they can lead people into overly-static and linear ways of looking at the world. Whitehead's philosophy is more holistic and dynamic. This means that, when we think of experience, we need to hold onto diagrams with a relaxed grasp, fully aware that experience is always more than images. Nevertheless, the diagrams may help viewers more fully understand Whitehead's concept of experience. In the narrative the experiencing subject is imagined as a human being, but it is important to remember that, in Whitehead's philosophy, there is subjectivity everywhere: in the infinitely small and the infinitely large. Even in the depths of atoms, and even in the depths of God, there is something akin to what is depicted in the diagrams: prehending, subjective form, and decision. However, in God, as Whitehead understands God, there is no perishing of immediacy. God is the inclusive and everlasting act of concrescence who shares in all finite moments such as those depicted above. (See Lesson Nineteen.)

Lesson Eighteen

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, page 229

Key Idea: The beauty of life is felt in contrast; the aim of life is to weave them.

Lesson Eighteen introduces an idea which is extremely important to Whitehead, and which he lists as among the eight categories of existence he seeks to illuminate in Process and Reality. This is the idea of contrasts. For some in the English-speaking world, the word contrast can suggest conflict; but for Whitehead it suggested complementarity. The yin-yang diagram in traditional Chinese thinking offers a helpful image of contrasts. Whitehead was interested in how we can experience objects in the world through contrasts, and also in how we try to weave our own emotions -- our subjective forms -- into contrasts. He believed that all experiencing subjects, anywhere in the universe, are seeking contrasts or, to use another word important to him, beauty. They - we -- seek harmony and intensity, neither to the exclusion of the other. In the very seeking there is a zest or vitality which, for Whitehead, is part of life's meaning. Even the adventure of the universe as One -- even God -- is enriched by and forever seeking a harmony of contrasts.

Lesson Nineteen

Relevant Text: Process and Reality, pages 342-351

Relevant Idea: God is a non-coercive guide and a fellow sufferer who understands.

Lesson Nineteen presents Whitehead's understanding of God. This is an aspect of Whitehead's cosmology which which many religiously-minded people find especially important: whether Jewish or Muslim or Christian, Hindu or Taoist or Buddhist. In Whitehead's philosophy God has two aspects: a non-coercive but guiding aspect which is home to all the potentialities which the universe can actualize, and which is within each experiencing subject as its own innermost lure toward full aliveness; and a receptive side which shares in the experiences of all living beings, anywhere and everywhere, and is affected by all that is felt. God is, as it were, the deep Mind and the deep Listening. Whitehead thought it more rational to believe in God, thus understood, than not to believe in God; and he believed that this way of thinking about God is consonant with the view of the universe we gain from post-mechanistic science. In a later book, Adventures of Ideas, he speaks of the guiding side of God as an Eros by which the universe is lured into adventure, moment by moment, epoch by epoch; and the receptive side as a Harmony of Harmonies within which, in certain moments, the restlessness of adventure drops away and people feel deep peace.

Lesson Twenty

Relevant Text: Process and Reality as a Whole

Key Idea: Why Whitehead? So many reasons.

Lesson Twenty brings the series to a close by articulating various reasons why people in different parts of the world are attracted to Whitehead's philosophy. To the many reasons identified in the video, one very important reason should be added. Many scholars in the academic world believe that Whitehead's philosophy can advance knowledge in specific disciplines: chemistry, physics, psychology, sociology, biology, philosophy, economics, business, culture studies. The work of the Center for Process Studies in Claremont, California, can introduce readers to developments in these and many other areas. It is the best single, online resource for finding resources and keeping abreast of developments within the disciplines.

At the same time, Whitehead's philosophy offers a way of moving beyond the disciplinary fragmentation that has separated academic disciplines from one another and from forms of practice, in real world, which might help guide the world toward sustainable communities. When it comes to practicing process thought, some Whiteheadian thinkers turn toward particular questions of public policy: economics,agriculture, manufacturing, education, governance. In this website, John Cobb's Ten Ideas for Saving the Planet and Foundations for a New Civilization offers an intimation of the policy-oriented directions. There is also much work being done today using Whitehead's thought encourage cross-cultural dialogue, including inter-religious dialogue. Why Whitehead? So many reasons.

This does not mean that Whitehead's philosophy has all the answers. For Whiteheadians the world needs many points of view, including many which offer critiques of Whitehead's own thinking. Whitehead hoped that his own ideas would be tested, applied, revised and, where necessary, replaced. And he did not want his philosophy to be turned into a dogma. Recall the point he makes in the preface: "How shallow, puny, and imperfect are efforts to sound the depths in the nature of things. In philosophical discussion, the merest hint of dogmatic certainty as to finality of statement is an exhibition of folly." (xiv) Process philosophy is more -- much more -- than Whitehead. It is an ongoing tradition, inspired by Whitehead's ideas, but moving beyond his thinking, too, fully cognizant that there are no final answers, only lures for feeling.